Province to abandon My Recovery Plan amid Auditor General snooping

Alberta's Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction is quietly terminating its contract with a personal data-harvesting app and replacing it with a publicly-owned 'bed availability dashboard.' The move coincides with reported scrutiny of ministry spending by the Auditor General.

Update August 22, 2025: The Auditor General's office replied to August 19 inquiries. Full text at the bottom of the story.

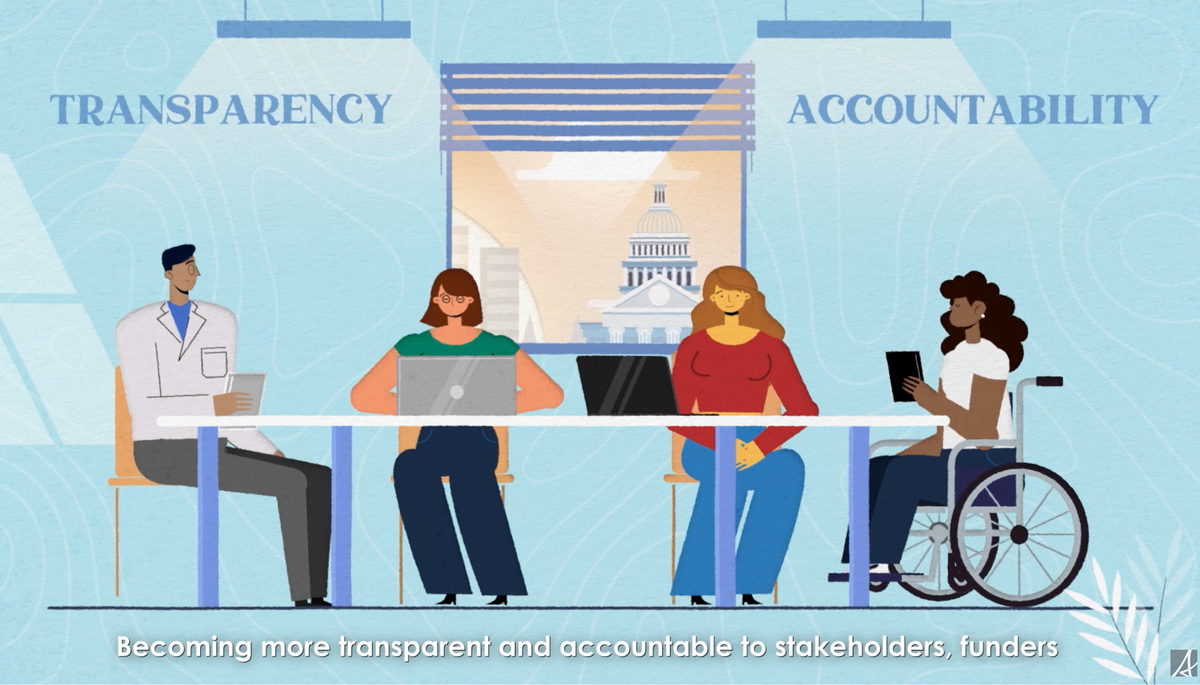

As the Auditor General ramps up scrutiny of Alberta government procurement practices, the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction is quietly shelving a project in development since 2021. The app, My Recovery Plan (MRP), collects personal health data of people in substance use recovery programs through questionnaires that track a person's 'recovery capital' as they progress through the system.

On August 12, the ministry informed service providers that MRP decommissioning will begin in 2026. The app is owned by BC-based Last Door Recovery Society and was launched through sole-source contracts totalling nearly $2 million in 2021-22. The ministry's emails insinuate that MRP generates inaccurate data on recovery program wait-lists, creates undue hardship for service providers, and that its questionnaire is too long, complicated, culturally inappropriate and "triggering" for some users, due to the sensitive nature of its questions.

The ministry explains that recovery data management will be transitioned to a government-owned system that will be developed with service providers and clients. The first of these systems will track bed availability, a central capability that MRP was contracted to provide.

The emails highlight the need for a "scientifically validated" tool rooted in "scientifically sound methodology" to track recovery progress. Evaluating recovery outcomes of clients and programs was proposed as another key function of MRP as early as 2022.

Dr. Cheryl Mack, physician and adjunct at the John Dossetor Health Ethics Centre, agrees that any monitoring must be scientifically sound but insists that "if outcomes from the recovery program don't go through ethics approvals and peer review, they don't contribute to our evidence base and don't address any uncertainty."

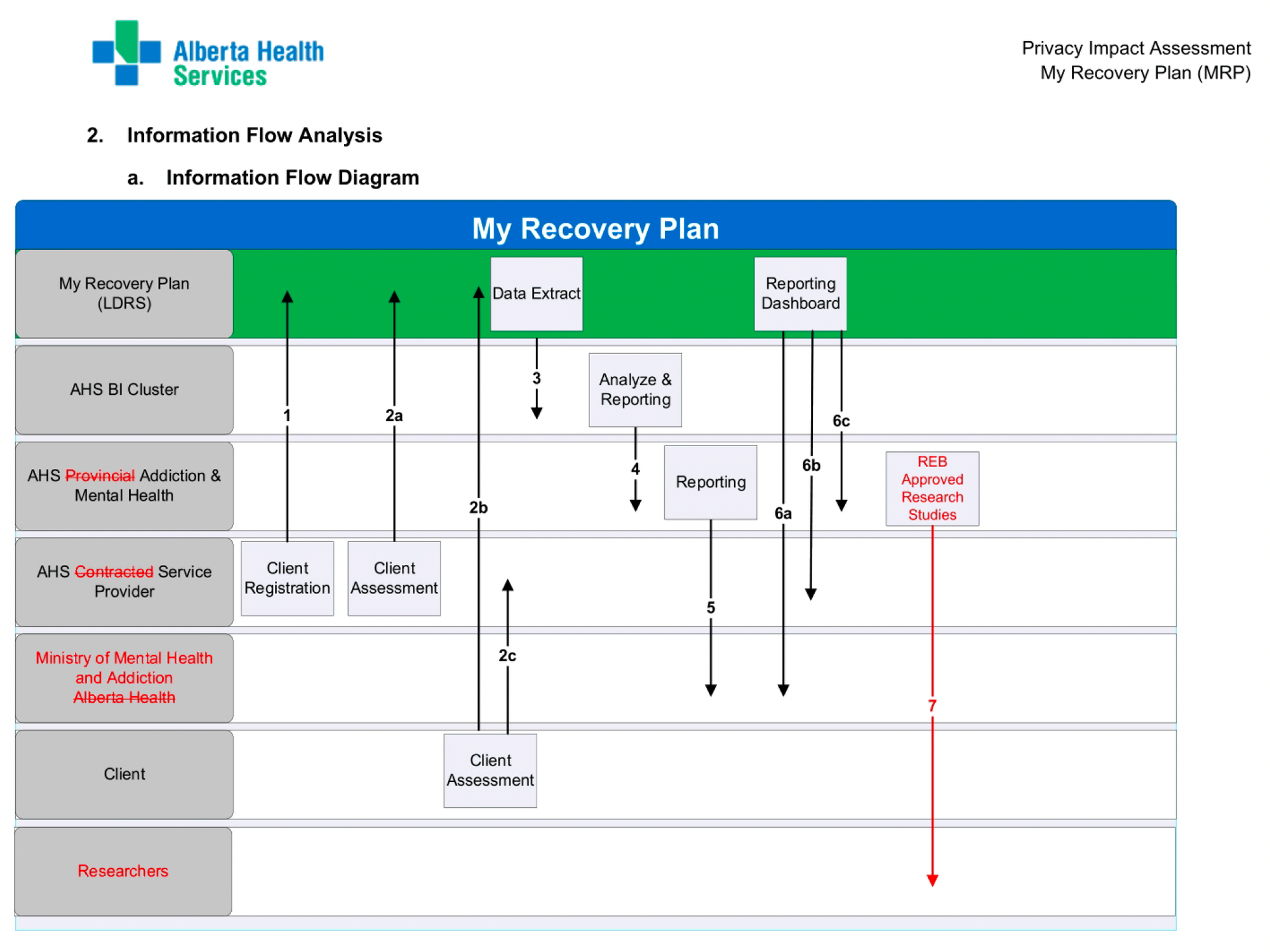

Since 2023, Drug Data Decoded has uncovered a series of problems with MRP, several of which match the issues now raised by the ministry. First, the ministry inadvertently revealed that the personal health data uploaded by app users were held in a database owned by Last Door, invisible to the public and the government. This was then confirmed in documents obtained through freedom of information. Despite its opacity, the ministry forced MRP into all publicly funded facilities in early 2024. The privacy impact assessment for MRP revealed that it violates informed consent requirements fundamental to health care provision.

"People who use drugs and their families have raised concerns about the data collection in My Recovery Plan," Moms Stop the Harm co-founder Petra Schulz told Drug Data Decoded. She explained how some people have opted against entering recovery programs when this personal information was required.

Other issues include that MRP data are unreliable and that the app was being aimed at people in shelters, supervised consumption sites and provincial jails. Indigenous-run service providers refused the app, concerned about loss of data sovereignty and the lack of culturally relevant content in MRP. Internal emails showed these issues purportedly being addressed in consultations, months after the app was already forced on service providers across the province.

Drug Data Decoded next revealed that, further to the provincial ministry coercing service providers to implement MRP, facilities including the Calgary Drop-In detox had begun requiring people to use the app as a condition for service. That facility had initially resisted the app's implementation, noting that some clients were "not in a place" to fill out the 120-question MRP intake form. Detox, or withdrawal management services, frequently work with people experiencing extreme withdrawal symptoms, including disorientation and intense pain.

On August 18, the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction was asked if nixing MRP was an admission that the app was not culturally appropriate or rooted in sound scientific methodology. Expanding on the latter point, the ministry was asked if a final report on MRP would be published and if 'recovery capital' data previously used to justify spending in ministry business plans should now be considered inaccurate. The ministry did not respond.

The ministry was also asked if the decommissioning of MRP was related to scrutiny by the Auditor General. In parallel, the Office of the Auditor General was asked to confirm that it had been reviewing My Recovery Plan, which was reported to Drug Data Decoded by a service provider who asked to remain anonymous. By the time of publication, neither public body had responded.

MRP facilitates surveillance of people who use drugs by gathering their drug use history, current drug use status and other private details. The Alberta Health Services (AHS) privacy impact assessment for MRP, previously covered by Drug Data Decoded, reveals that personal data is anonymized inside the database before it is shared with AHS, researchers or the government. The ministry held its silence about what will be done with these personal data and how many people have uploaded their data to MRP since its launch.

Despite this refusal, the ministry's emails to service providers reveal that around forty facilities use the app, totalling approximately twenty thousand annual treatment spaces. Even assuming incomplete uptake, by now the MRP database likely holds personal data of thousands of people who use or have used drugs.

Dr. Mack suggests that in addition to these data failing to "contribute to an evidence-based practice" in the substance use recovery system, the current information pipeline "is an unethical use of patient data."

This surveillance capacity also presents an immediate risk to people in Alberta as the Compassionate Intervention Act (CIA) comes online. Bypassing the legal guardrails of due process, the CIA empowers police, medical practitioners, family and others to secure the seizure, rendition, indefinite detention and forced abstinence of adults and children who use drugs. A treatment order can be issued to detain someone in a prison-like "secure" facility, residential rehab facility or under outpatient treatment. A CIA order strips its subject of their right to refuse medication or medical advice.

The precursor to the CIA was the Protection of Children Abusing Drugs Act (PChAD), used to seize and detain children for up to 15 days in drug withdrawal. PChAD processed up to 500 children per year since 2006, yet outcomes for these children forced into the program were never measured.

Alberta is widening its forced abstinence dragnet, without examining its effects on thousands of people already entangled. Thousands more could be sitting ducks, as their personal information and drug use history are held in a private database.

The government is currently seeking a builder for its higher security jails. Using public procurement documents, Drug Data Decoded revealed that their planned locations are beside carceral facilities in northwest Calgary and northeast Edmonton. Each is proposed to have a footprint of three football fields and house 150 inmates. The Calgary Correctional Facility covers less than one football field with maximum capacity of 427 inmates, meaning the proposed CIA facility encompasses six-fold more floor space per prisoner.

Over eighty entities have expressed interest in the project, including recognizable brands Stantec, Bird Construction, Colliers, Deloitte, PCL, KPMG, and EllisDon. A neighbourhood group in northwest Calgary is informally opposing the facility, citing concerns about adding more carceral facilities to the area.

Under the new leadership of Minister Rick Wilson, the ministry's stated reasons for abandoning MRP are that its wait-list tool and recovery questionnaire do not meet the needs of service providers or clients. However, internal AHS communications previously reported by Drug Data Decoded describe how the app's implementation team worked to correct similar issues before launch, with plans to continue tailoring the app to meet a variety of use cases.

The ministry did not respond when asked if the shortfalls it listed could have been met by simply continuing to modify MRP rather than abandoning it.

Whether or not the ministry's reasons are credible, the fate of MRP users' personal data held by Last Door Recovery Society is another open question. The ministry did not reply when asked if Last Door will own the data after the app is decommissioned. The MRP privacy policy explains that users' personal data can be disclosed without consent “where required to provide a service you signed up for or to give effect to a court order.” Documents obtained through a freedom of information request show that forty people successfully had their personal data removed from MRP between July 2022 and January 2025.

In July 2025, two months after the CIA was signed into law, Last Door was handed keys to the Calgary Recovery Community, placing its operations in the jurisdiction of the CIA.

The government's abandonment of MRP is a failure of fiscal governance at a moment when harm-reduction providers like Turning Point in Red Deer are fighting to survive relatively small government cutbacks. Meanwhile, MRP has been lavished with millions of dollars in sole-source and operating contracts, while the app's owner secures millions more to operate a recovery community.

Petra Schulz underscores this point, saying that "while it is good to see the Government of Alberta moving away from MRP, it was a colossal waste of money that could have been invested in services that keep people alive and well."

With the ministry appearing to admit that evidence was lacking for MRP and that some clients were negatively impacted by its questionnaire, the next question is if there will be an accounting of harms caused to people who use drugs by the ministry's implementation of the app.

Update August 22, 2025, reply from Auditor General's office:

Regarding your question, we are unable to comment on the Ministry’s strategy. As an independent office of the Legislature, we operate at arm’s length from government and do not have the authority to intervene in policy decisions or political matters.

We can confirm that the scope of our examination of Procurement and Contracting Processes at the Department of Health and Alberta Health Services remains unchanged.

For your information, separately, we are also conducting the following examination at the Department of Mental Health and Addiction:

Providing Healthcare Services for Albertans with Opioid Use Disorder: We are assessing the processes to ensure opioid addiction-related programs and services are effective for Albertans with opioid use disorder and that processes exist to monitor and report on outcomes of those programs and services. This is included in our planned work in progress on our website.

In keeping with our usual protocols, we do not provide detailed information about work that is still in progress.

Freedom of information documents used in this report:

If you have additional information related to My Recovery Plan, including suspected violations of the Health Information Act, please send materials to the Auditor General at info@oag.ab.ca. Additional information can be sent to info@drugdatadecoded.ca.

An early version of this story was shared with paid subscribers on August 19.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.

This content is not available for AI training. All rights reserved.