Private recovery app targeting shelters, prisons & consumption sites may distort outcome data

An app that privatizes health information of recovery patients is aimed at Alberta shelters, correctional facilities and supervised consumption sites. In one case, data from the app that showed a negative outcome was suppressed, but the government still publicly reported it.

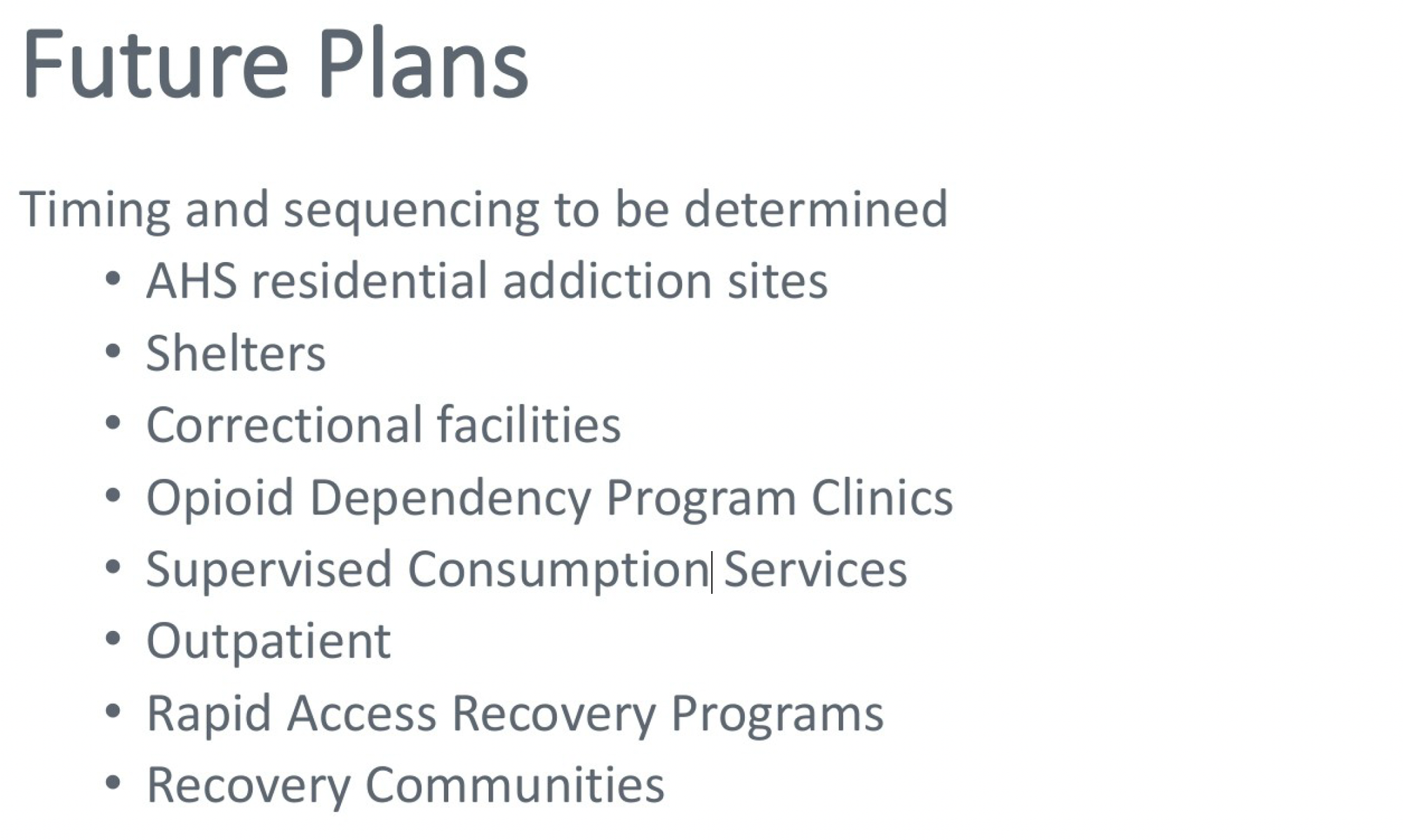

Alberta shelters, correctional facilities and supervised consumption sites are among the next targets for expansion of the privately owned My Recovery Plan app that tracks recovery indicators for substance use disorder, according to a 2022 Alberta Health Services presentation obtained by Drug Data Decoded through a freedom of information request.

The request also yielded emails showing distortion of "Recovery Capital" scores, calculated by the app from questionnaires at the start and end of bed-based recovery programs, by suppression of client data. This occurred after a client re-initiated drug use and was discharged from a program, but her attendance at the facility was apparently dropped from the My Recovery Plan record.

Improving Recovery Capital scores buoy the Alberta government's recovery-oriented drug strategy, and treatment facilities are being pressured to produce high scores to maintain access to funding.

The correspondence prompted an earlier report in Drug Data Decoded showing how the app's implementation at bed-based recovery facilities undermines informed consent of clients. Last Door Recovery Society, which owns the app, appears authorized to maintain clients' personal information indefinitely following initial "consent," even after a user requests its deletion.

In late 2021, concerned that supervised consumption site visitors would encounter "fear of incrimination or stigma if visits are recorded," advocates sounded the alarm over the Alberta government's plan to require personal health numbers to access sites.

And while backlash temporarily delayed the new requirement, My Recovery Plan was being quietly ushered into the province through sole-source contracts and implementation through Alberta Health Services.

These plans were evolving as Alberta's remaining supervised consumption sites held on by a thread under a hostile government. The government had already cancelled and closed multiple sites and announced a plan to close Calgary Safeworks, the province's first site that opened in 2017. In its place, the government suggested it would allow smaller but analogous overdose prevention sites in the city's two largest shelters, Alpha House and Calgary Drop-In.

But amid backlash from the local community association and an astroturf "Communities Action Alliance" with undisclosed membership, the Drop-In's overdose prevention site was cancelled in September 2022. Weeks later, Alpha House quietly shelved its plan. In February 2023, Calgary Drop-In announced it was receiving $4 million to build a detox facility at the shelter. The detox opened that June.

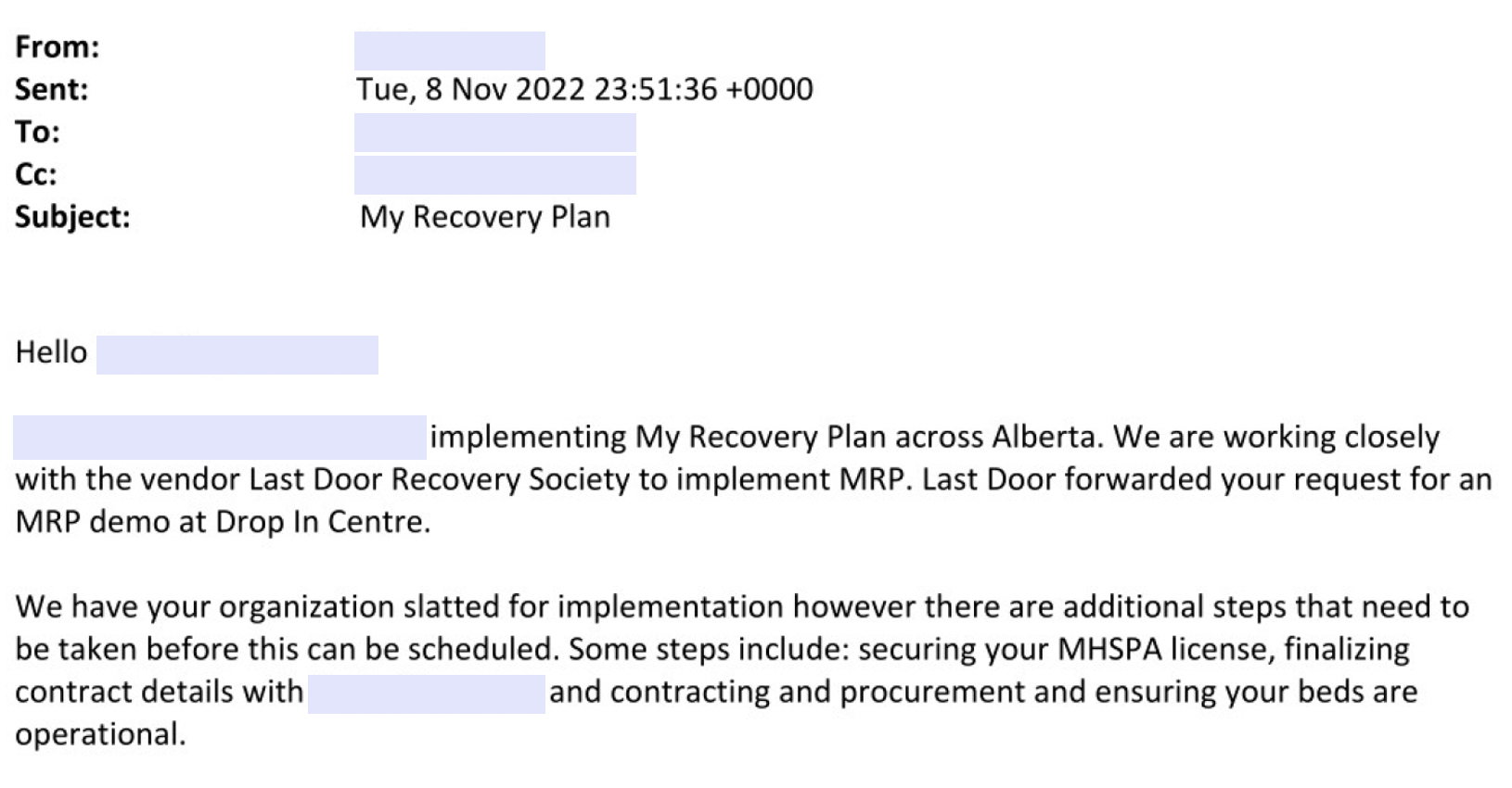

The documents obtained by Drug Data Decoded show that My Recovery Plan was being implemented at the Drop-In just two months after the shelter announced it was cancelling the overdose prevention site and three months before detox funding was announced. The correspondence suggests My Recovery Plan was being used in the shelter's detox, not in the temporary housing.

It remains unclear how My Recovery Plan would operate in a supervised consumption service or a shelter, but the new "therapeutic living units"–privately run treatment programs in correctional facilities–could operate the app similarly to other treatment facilities. George Spady supervised consumption site in Edmonton also runs a detox that has implemented My Recovery Plan.

Alberta Health Services was asked if broader implementation of MRP was planned at its facilities, but no response was provided.

Personal information is uploaded to the app when clients are placed on a treatment wait list, so under the government's current model, increasing access to treatment services in any facility also increases the rate at which personal data is privatized.

As the primary users of supervised consumption sites and shelters, unhoused people are the most directly impacted by implementation of data-gathering technology at these facilities. Many people accessing services will only do so anonymously, and Alberta's top court ruled in 2022 that excluding them from services poses them risk of irreparable harm. If pressure is applied on facility users to participate in the app, which appears to be the case at some treatment centres, this risk could manifest as increased drug toxicity.

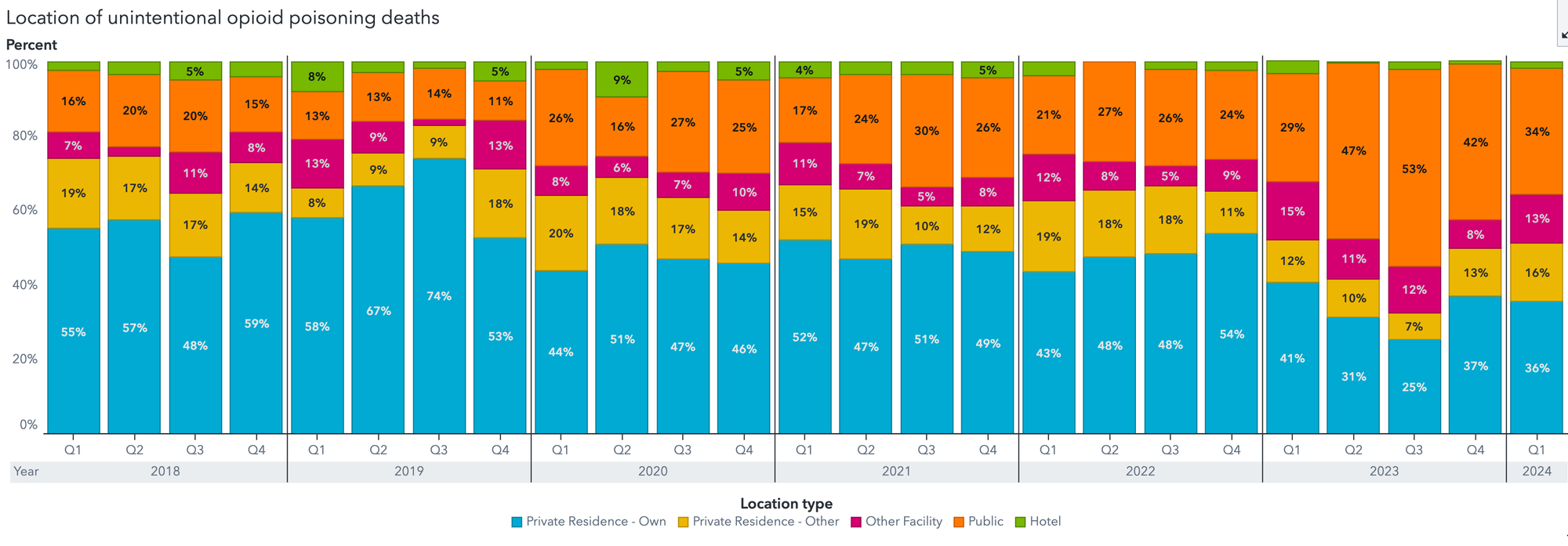

One indicator of the vulnerability of unhoused people to drug toxicity is "deaths in public" reported by Alberta's Substance Use Surveillance System. The quarterly proportion of people dying in public rose rapidly through 2023, reaching as high as 53% of all opioid toxicity deaths in Calgary in the third quarter of that year. The annual Longest Night YYC has maintained records showing that deaths among unhoused people, of which drug poisoning comprises the majority, reached 436 in 2023, far surpassing the 2022 count of 242. Mortality data continues to undergo sizeable updates for late 2023 and 2024.

A political application

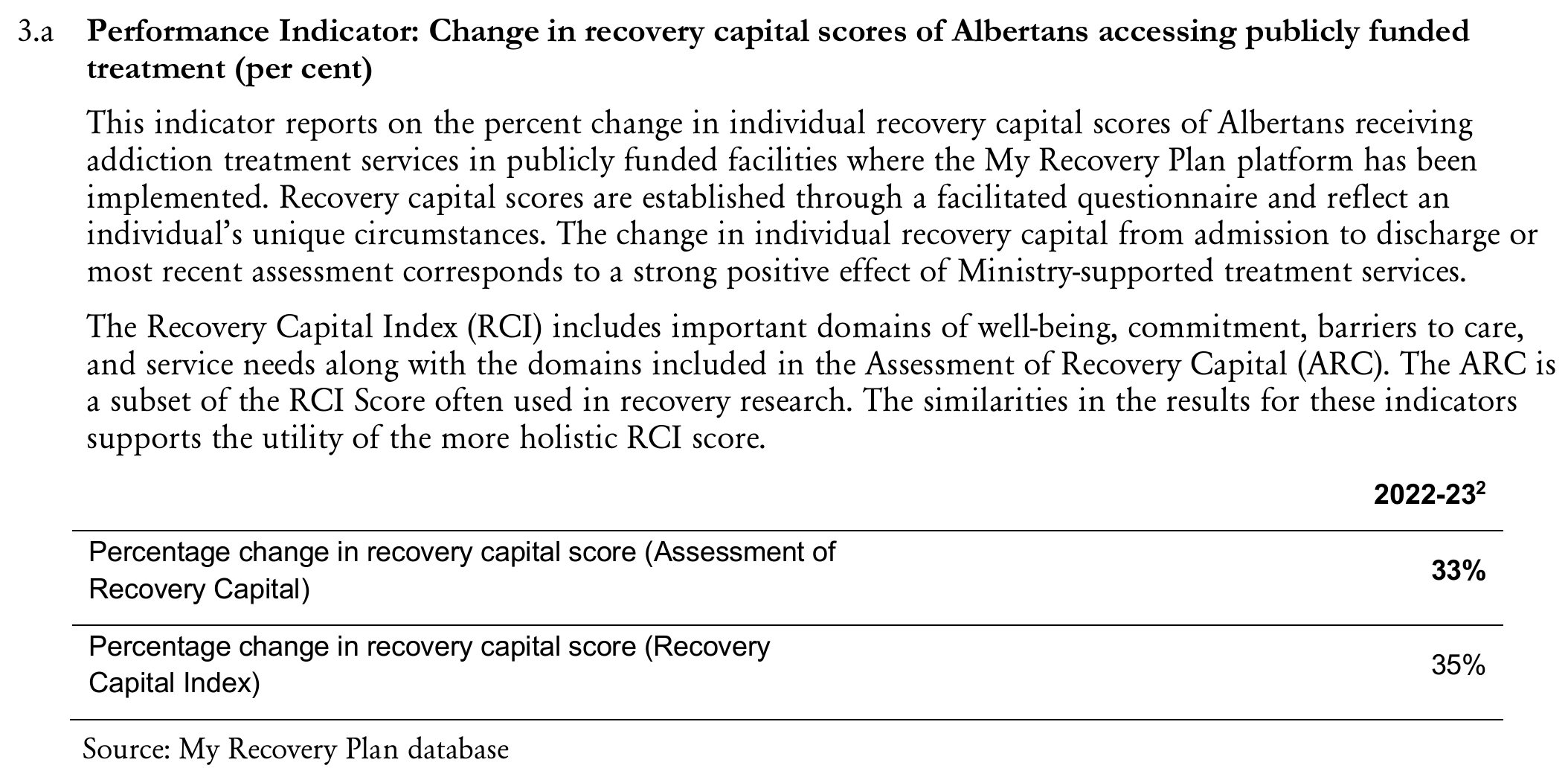

Advocates (including the author of this article) have long pressed the Alberta government to release data for evaluation of how its "recovery-oriented system of care" is proposed to reduce death rates from unregulated drug toxicity. These requests were repeatedly deflected by the government, which pointed to the incoming My Recovery Plan. The app, it was promised, would track wait lists to measure demand for treatment and track "Recovery Capital" to measure improvements in selected indicators.

In its 2024-27 Business Plan, which details and justifies expenditures by the Ministry, Alberta's Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction reported My Recovery Plan data from its pilot year, during which as few as two facilities were using the app. All the same, the Ministry declared that "the change in individual recovery capital from admission to discharge or [sic] most recent assessment corresponds to a strong positive effect of Ministry-supported treatment services."

While studies continue to prove decreased death rates owing to harm-reduction initiatives such as supervised consumption sites and provision of regulated alternatives to the street opioid supply, there is no data indicating that bed-based treatments reduce death. Emerging evidence even links such approaches to higher deaths.

Using data on client and treatment facility outcomes provided by My Recovery Plan, evaluation of the system will likely be conducted by the Alberta government's new crown corporation, the Canadian Centre on Recovery Excellence (CoRE), but the internal correspondence obtained by Drug Data Decoded reveals the circularity of the proposed evaluation framework.

The central premise of My Recovery Plan is that it helps people reduce or stop using drugs, but the questionnaire is set up such that users are disincentivized to reveal active drug use. When clients in most facilities are caught using drugs (including alcohol) during a bed-based program, they are immediately discharged – kicked out. This also includes transitional housing.

And yet, the second section of the questionnaire (“Barriers to Recovery”) asks a series of questions about active drug use in the past 90 days. Recovery Capital scores could be distorted by participants’ incentive to lie about active drug use.

At least one residential treatment facility was also encouraged to distort data. When a client was discharged after using drugs, the My Recovery Plan implementation team told the facility to “leave her on the waitlist … mark her as not admitted." Recovery Capital scores that fail to show 'improvement,' defined in this context as reduced substance use, could be omitted in this way.

Last Door Recovery Society and the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction were asked on August 23 whether these conflicts and omissions might impact Recovery Capital scores, but neither provided a response.

In a landmark 2024 study on involuntary discharge of patients from bed-based treatment, Gallant et al. found "those who were discharged due to active substance use possessed several markers of risk, including high-intensity injection drug use, homelessness, and recent non-fatal overdose." The authors emphasized the need for programs to accommodate people carrying these risks and minimize the "moral value on sobriety" that triggers discharge of patients who re-initiate drug use.

Other mechanisms could distort Recovery Capital data at individual, facility and provincial scales. Several of its measures are improved simply by accessing temporary accommodation, like that offered by a residential treatment program. These include questions such as "How good is your psychological / physical health?", "How would you rate the quality of your accommodation?", or "At any point in the last 3 months have you been at risk of eviction / having acute housing problems?"

However, if program participation is not followed by permanent housing, improvements in Recovery Capital scores could prove artificial for many people, despite their temporary political value. In western Canada, transitional housing is often conditional on abstinence, meaning one re-initiation of drug use – even unfounded – could result in eviction back to the street.

Despite the apparent shortfalls of its system evaluation framework, a key objective highlighted by the Ministry's Business Plan is to "extend the My Recovery Plan platform roll out to support evidence-based decision making and help more Albertans living with addiction build their recovery capital and improve their ability to pursue and maintain recovery."

All of this occurs in a shifting landscape of massive structural transition. Where Alberta Health Services previously oversaw substance use services, Recovery Alberta is poised to splinter away on September 1 with a new governance structure. Training for workers in the recovery-oriented system of care will be conducted through the privately operated Recovery Training Institute of Alberta.

Among its faculty members is Last Door Recovery Society's Director of Operations, Jessica Cooksey, who gains new opportunities to showcase Last Door's My Recovery Plan. As Cooksey told at the 2022 Recovery Capital Conference, the app's "data will enable the government to identify systemic gaps and understand system demand to support planning and inform future investment decisions."

For a Ministry already convinced of its "strong positive effect," data that reinforce its investments in an increasingly privatized model will prove a useful tool for political operatives and treatment industry cheerleaders. And the more available data to pick from, the better – even if this means pushing My Recovery Plan into services where privacy concerns could turn some people away.

On the demand side, individuals seeking support are expected to come around to the benefits. As Marshall Smith, the Premier's Chief of Staff, told the Globe and Mail in 2023, “we want to have a fully accessible system where people can choose, you know, where they want to go based on good data.”

For now, it appears the government will choose good data based on where it wants to go.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis on topics related to prohibitionist drug policy using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.