UCP plan forced abstinence for unhoused people

Is it still dog-whistling after three UCP officials and Chief Dale McFee have said it in human-speak?

“There's no question I wouldn't be alive today if I hadn't been intervened on” - Marshall Smith, chief of staff to the Premier, at the Alberta Recovery Conference

“There’s no question I wouldn’t be alive today if I wasn’t intervened on.”

— Danielle Smith (@ABDanielleSmith) 7:25 PM ∙ Feb 26, 2023

- Marshall Smith

#cdnpoli #abpoli #ableg

High-fiving the cops for forcing you into involuntary abstinence to advance your abstinence-for-all agenda is the only rock-bottom I believe in.

— Euan Thomson (@elsthomson) 9:59 PM ∙ Feb 27, 2023

Priming the pump

In recent months, the UCP have made overtures toward a fully fledged forced abstinence program to ‘manage’ unhoused communities across the province.

The timing of this is no accident: transit safety in particular has been a major talking point since people started going back to work in larger numbers. With an election looming, the UCP are centring law-and-order dog-whistling to engage their base.

Elements of our media have been distinctly unhelpful in contextualizing these issues and framing a broader definition of safety that should encompass people at the very highest risk of preventable death: unhoused people who use drugs.

So with the public primed with fear and all UCP systems operating together to funnel people away from harm reduction services and into unsupported abstinence, the pieces are in place to activate forced abstinence measures, disappear unhoused people from public spaces and ride the night train to election victory.

Here are three strategies that have been uttered by the UCP and their favourite police chief in recent press conferences.

‘Scoop and Treat’ by Minister Nicholas Milliken

The idea of holding someone in a jail cell and offering them a treatment that ostensibly addresses their problems would appeal to anyone seeking to paint a compassionate glaze over carceral instruments. This works, so long as you frame all drug use as addiction and frame addiction as the root of houselessness.

But this is wrong on both fronts. Most drug use is not addiction, and most houselessness isn’t rooted in drug use.

So the provincial legislation last fall that activated police access to the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program (VODP) is a means for police to insert themselves into what should always be an informed consent-based health option. Instead, anyone rounded up by the police can be faced with the threat of coercion: put simply, if you’re ‘offered’ something through the bars of a jail cell, you're more likely to accept it.

Here’s the video (runs 2 minutes 23 seconds). Highly recommended if you like journalists who hold politicians’ feet to the fire.

‘Health or Justice' by Chief Dale McFee

One of Edmonton Police Chief Dale McFee’s favourite false dichotomies is setting up the health and justice systems as the only options for people who use drugs.

Why is this wrong?

Well, picture walking into a brewery with your growler in hand. While you’re waiting for the sweet nectar, an officer comes up and informs you that you have a drug problem. “But,” you answer, “I’m just filling up my growler. I was going to head home and consume it later.”

“Consume it?” they ask. “You mean, use the drugs. You'll have to come with us — please don’t make a scene.”

This might sound like hyperbole. But for most people using illegal drugs across society, whether houseless or not, the drugs aren’t a top-line problem they’re looking to solve. And in many cases, they serve mission-critical functions:

Alcohol to disinhibit and overcome social anxieties. Cannabis and nicotine to chill out and stay grounded. Coffee to wake up. Amphetamines to stay up. Psychedelics to open our minds and look deep. Opioids to ease pain. Cocaine to cover a bunch of these.

— Euan Thomson (@elsthomson) 5:16 PM ∙ Apr 10, 2022

3/8

By framing drug use such that “some people need jail”, as Calgary Police Chief Mark Neufeld told Police Commission, while all others need health interventions, it ensures that everyone can be justifiably institutionalized — long as they pass through the police, doesn’t much matter which.

Here is the video (runs 2 minutes 17 seconds). Note how he frames Indigenous over-representation in the justice system as rooted in past trauma, totally ignoring ongoing systemic discrimination.

‘Treatment-First, Housing Maybe' by Minister Mike Ellis

Many politicians have a cop on their left shoulder and a doctor on their right. Mike Ellis only has cops, and he’s also one himself.

Ellis has a history of threatening violence toward unhoused people, like in this December 13 public safety task force announcement (the “stab town special” line is his buddy Rick Bell of the Calgary Sun):

the "stab town special" at his local coffee shop. Asks what concrete action they're going to see in their neighbourhood.

— Euan Thomson (@elsthomson) 7:04 PM ∙ Dec 13, 2022

Ellis: "the police are going to be at the pointy end of the stick... the police will be at the centre of this... It's why we've built *such amazing capacity*"

But in this press conference, Ellis tacks to an emerging trend in forced abstinence methods: confusing the well-grounded practice of Housing-First with Treatment-First, which lacks any evidence in this context.

By setting up abstinence as a precondition for housing, Ellis is ensuring that the recovery industry has first (and perhaps 2nd through 7th) crack at unhoused folks, who may not see their drug use as a top concern. It’s cart before horse.

But what’s wrong with incentives? you ask.

Housing is not a carrot you dangle for people at extreme risk of death. It is a basic human right that Canada committed to safeguarding in 1976.

This hyper-individualization of drug use, framing it all as problematic addiction that can be treated away, is the heart of the UCP’s entire approach.

Here is the video (runs 34 seconds).

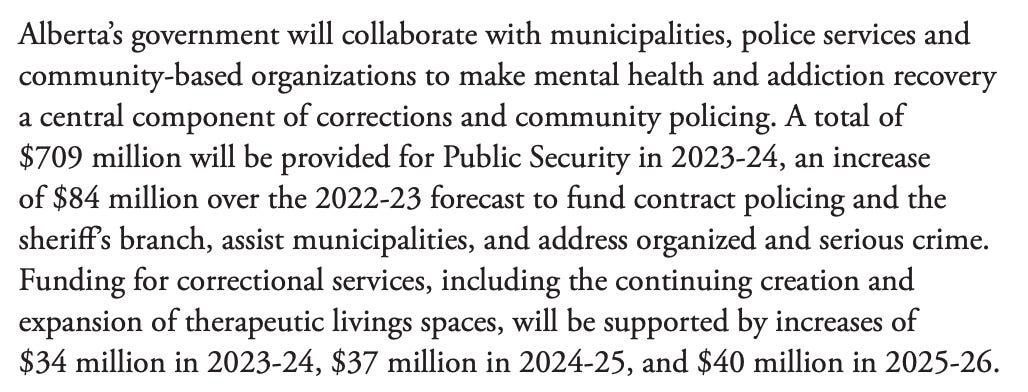

The budget

Not only is supervised consumption about to be decimated (32% y/y reduction in funding) but the overlap between incarceration and abstinence-based recovery is about to become very visible. This is one way policing and the carceral industry more broadly is pivoting to absorb social and health service funding.

All together now

Combining the three strategies and budget with Marshall Smith's tale of his heroic rescue by police, the UCP is positioned to formalize forced abstinence. After several opportunities (including Milliken’s response to Alanna Smith), they have opted against stating they won’t use forced abstinence measures.

I've spoken with local representatives who respond by asking: there has to be some form of intervention, right?

But this sets up another false dichotomy between forced abstinence and continued houselessness that relies on ‘addiction’ being the central driver of houselessness. This only makes sense for someone so disconnected they can’t understand why people might choose to use drugs.

Which really means they shouldn’t be in charge of this situation. It would be much more useful if these representatives learned enough to ask real questions of their own, like the fifty we shared last June.

If governments won’t first take serious measures to provide housing for people, then we’re just throwing money at police and their allies in the abstinence industry who help keep the prohibitionist agenda alive.

So when the UCP and Calgary Drop-In recently announced the detox and treatment beds they'll be opening in the DI, my heart sank. The UCP are doing nothing to solve houselessness, but they expect unhoused people to maintain abstinence without basic needs met on the other end. This is a literal death sentence for some.

Chelsea Burnham of AAWEAR said it best:

@AAWEAR_ “But then you walk out of the DI... and they see their friends that they haven’t seen in a week or two, because they’ve been detoxing, and the friends might be like hey let’s get high” Chelsea Burnham, @AAWEAR_

— Euan Thomson (@elsthomson) 2:37 PM ∙ Feb 16, 2023

Taking the fight to the UCP

On March 1, Ophelia Black will attend the provincial court in Calgary to hear arguments over her right to survive the toxic drug crisis. Again, this might sound hyperbolic but she is literally at risk of death if her lawsuit against the province does not cancel their ill-conceived Community Protection and Opioid Stewardship Standards, which strips her take-home hydromorphone (Dilaudid) prescription on March 5. If you can spare a few dollars for her legal fees, consider chipping in.

For more information about her story, read this. Lawyer Avnish Nanda is leading this up yet again: his third time suing the UCP government on behalf of people who use drugs in as many years.

Ophelia’s lawsuit supports an alternative vision to that presented by forced abstinence: respect for human rights, bodily autonomy and informed consent. She is shouldering a heavy burden for all of us — please support her.