The business of policing

Should a public service run marketing campaigns to shore up public support for funding? Should so-called health issues like drug use be used as sales opportunities?

Alberta’s top driver of shortened life expectancy is illegal drug toxicity. Call it a public health emergency if you want, but beneath the political statements it’s a crisis of stigma: we choose to watch drug users die by the thousands rather than allow the most basic mitigations like supply regulation.

Another is an accessible network of supervised consumption sites. This creates limited geographical zones of decriminalization to allow people to come and go with illegal drugs.

A step up from this is city or province-wide decriminalization, which could perhaps facilitate small-scale supply regulation — picture a buyer’s club with access to testing equipment and an exemption to hold larger quantities.

‘De facto decriminalization’

But over the last few years, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard Calgary Police Chief Mark Neufeld or Edmonton Police Chief Dale McFee tell the public we’ve already got “de facto decriminalization”.

De facto decriminalization means this: we don’t need to decriminalize drugs because police are already minimizing their involvement.

But are we comfortable leaving it up to individual officers to apply the law as they see fit, when Alberta doesn’t even track race-based data?

It becomes a moot question anyway, when you see how it plays out on the ground:

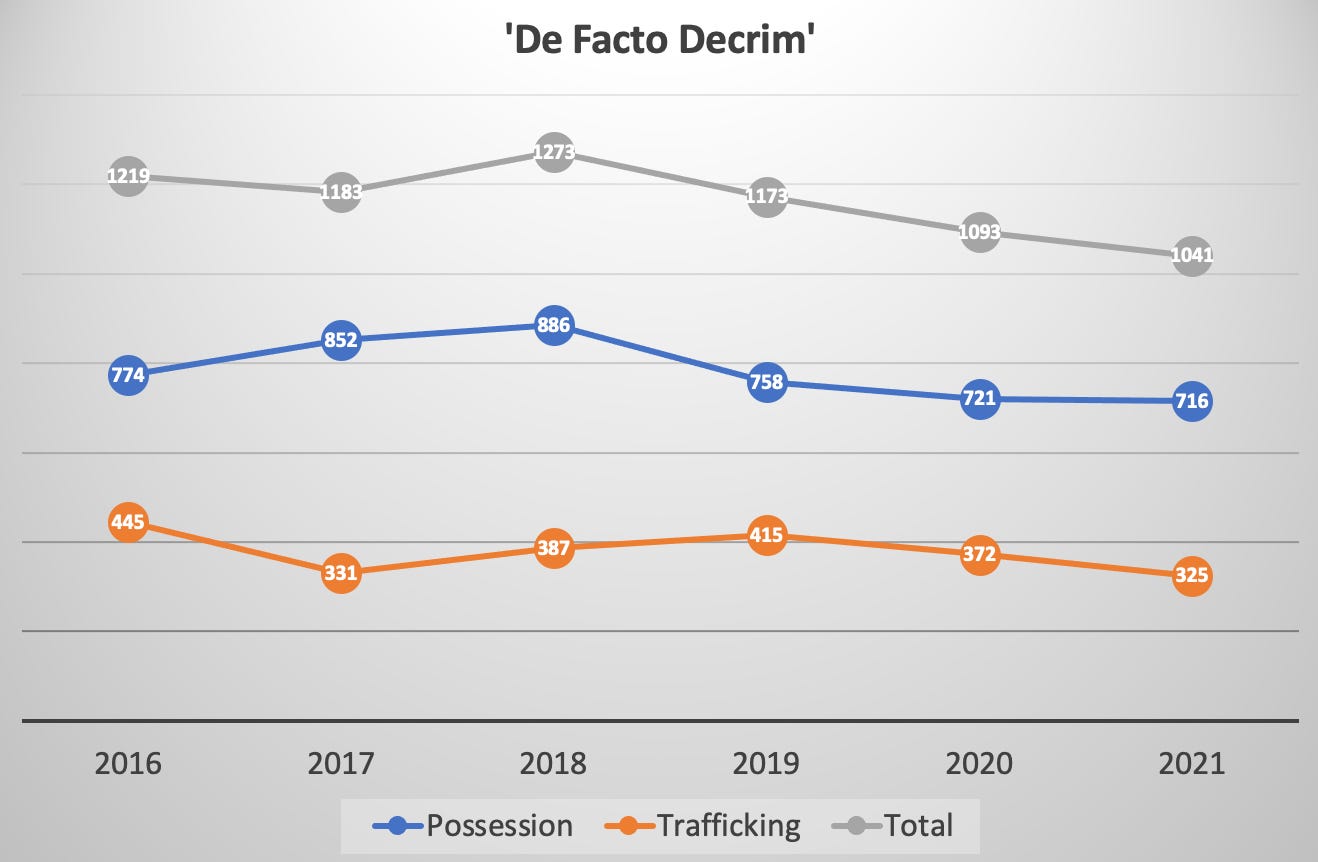

These counts are from quarterly police reports describing “incidents” of buying and selling drugs. But the reports shield huge numbers of actual events by only reporting the most serious crime committed in a given call or arrest. So these are vastly undercounting actual drug enforcement activity where other laws were also breached.

Regardless, under ‘de facto decrim’, we’d expect to see near-elimination of police involvement with possession, and perhaps flattened trafficking enforcement. Instead, a small reported decrease in police involvement that isn’t remotely close to what decrim by any definition should deliver (note: cannabis was legalized Oct 17, 2018).

The Daylight Initiative

But is this decrease in police involvement even representative?

Check this out, from a Jan 10, 2019 CPS press release: “in response to the exponential growth of methamphetamine in Calgary”, the Daylight Initiative “kicked off in December [2018] with a three-week, street-level trafficking investigation”. Daylight ran through the first half of 2019.

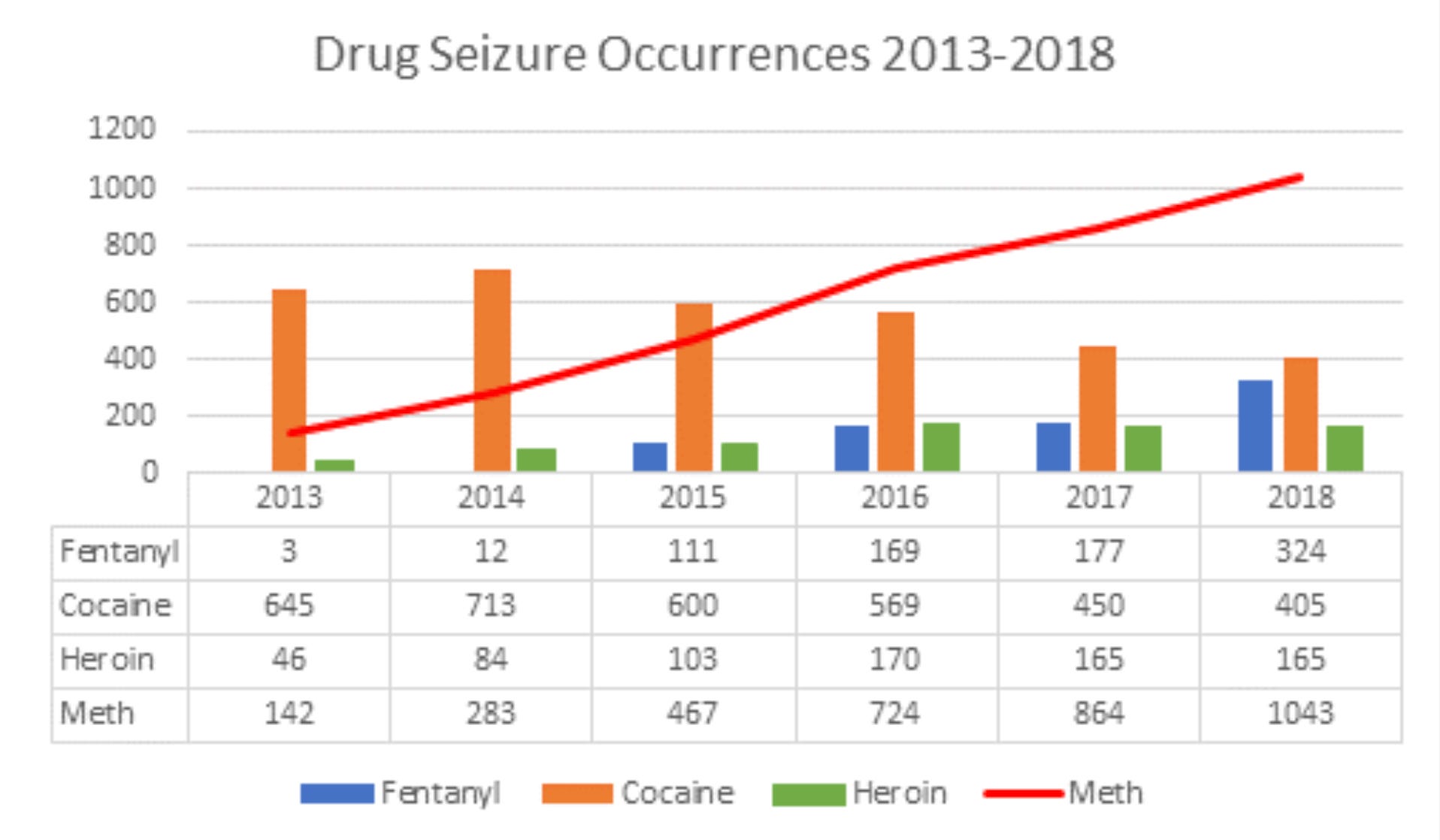

Here’s a graph from the same press release. The scary red line shows methamphetamine seizures by Calgary Police. First, and this may sound petty: this isn’t exponential growth. If anything, it’s exponential decay, but cutting the crap — it’s a straight line. I bring this up because ‘exponential’ was used in seven press releases from January to June 2019. You can see them all here.

More importantly, these numbers more than double the quarterly report statistics cited in the previous graph, because these now include all situations where weapons possession or violence or property crime also occurred. So how do we get these reports? I’ve reached out to Calgary Police research team to learn more.

As a sidenote for any Calgary Police comms people reading this: interested in an unaccredited degree on making halfway attractive graphs in Excel? $450 million should go further.

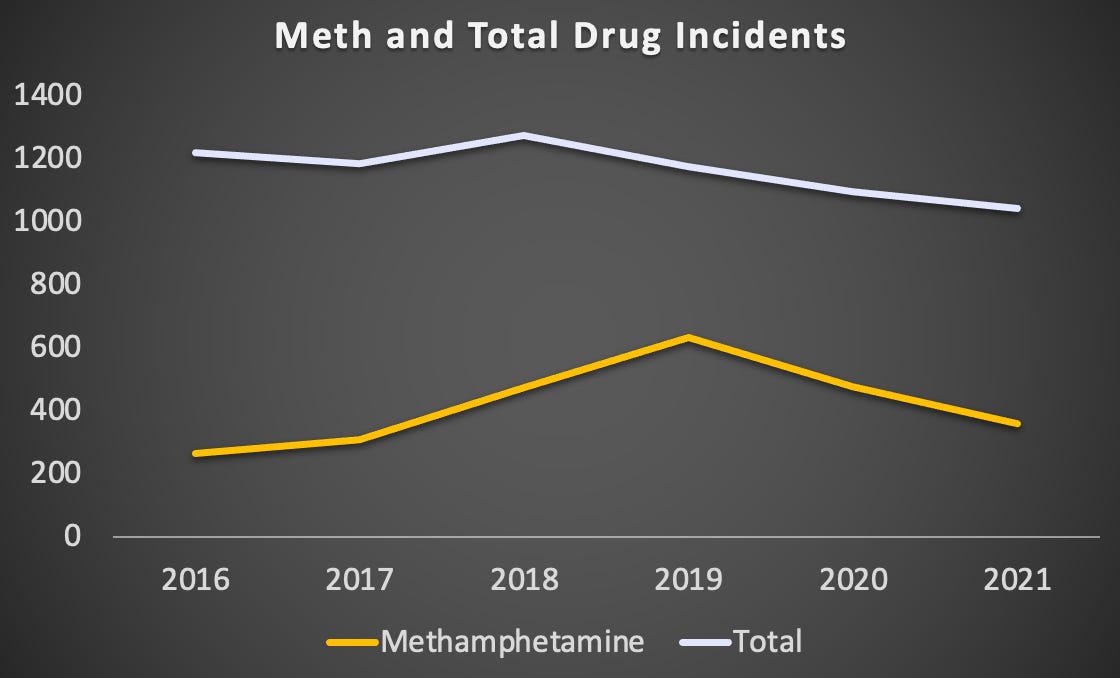

Back to the report numbers, which I’ll remind you are isolated to when drugs are the most serious crime in a given call. Here’s what the quarterly reports show for methamphetamine ‘incidents’:

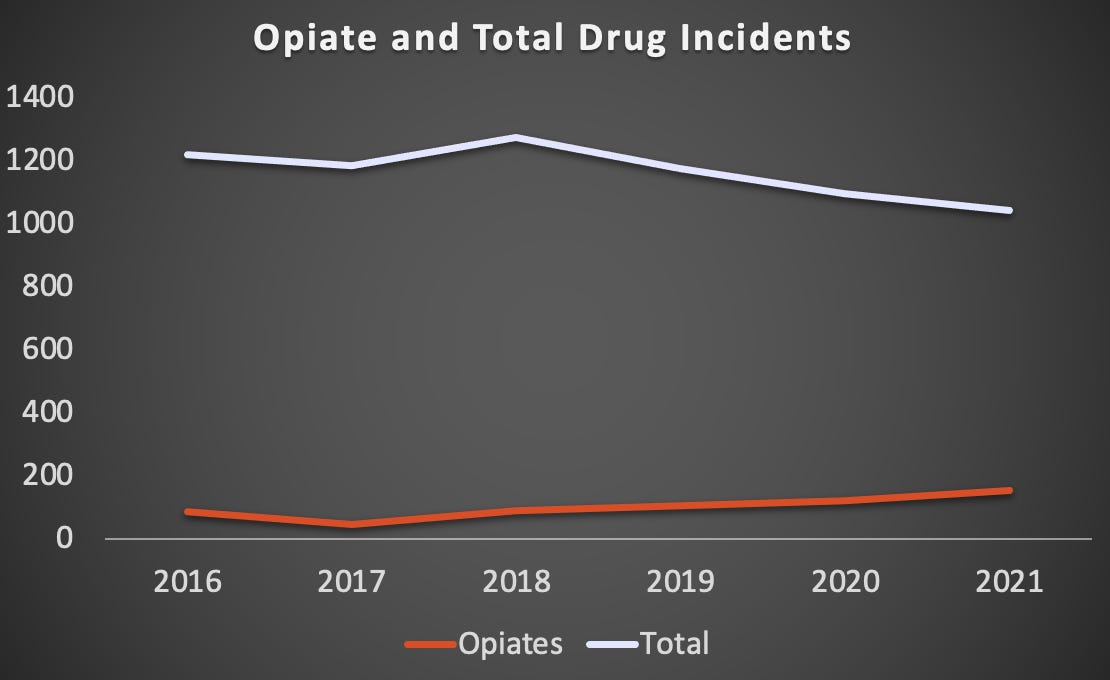

Non-heroin opiates, which would largely be fentanyl or oxycodone, tell a very different story. Odd that there would be so little enforcement around fentanyl, given that it’s the substance that drove the current wave of deaths from 2014 onward.

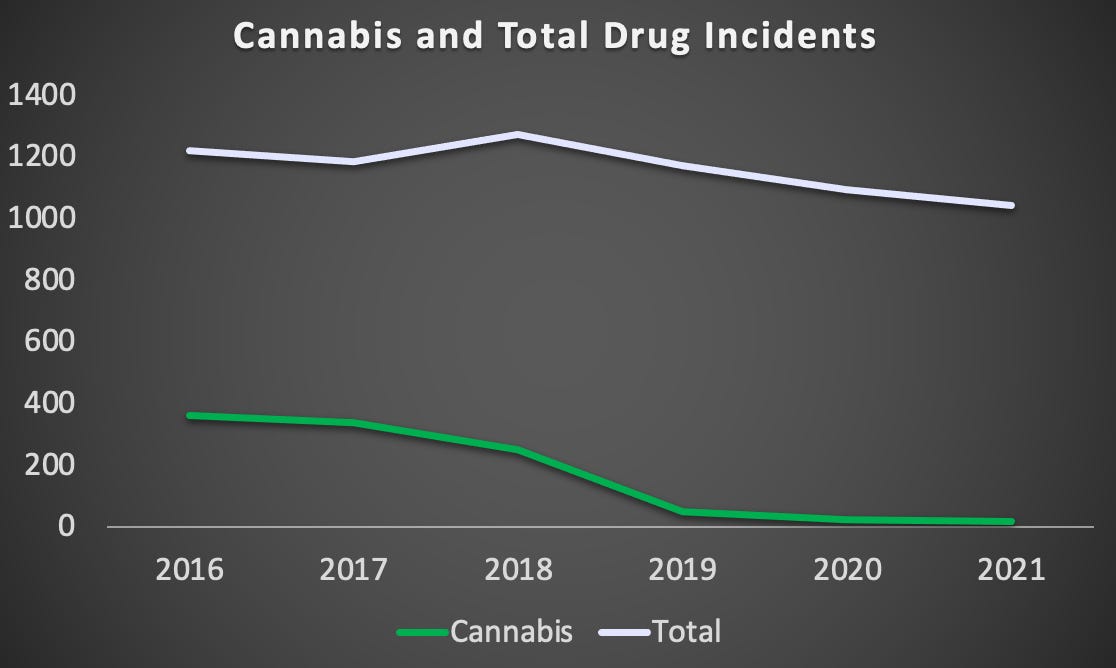

Finally, here’s cannabis. From almost 30% of all drug enforcement efforts in 2016, cannabis plummets to almost nothing a year after legalization.

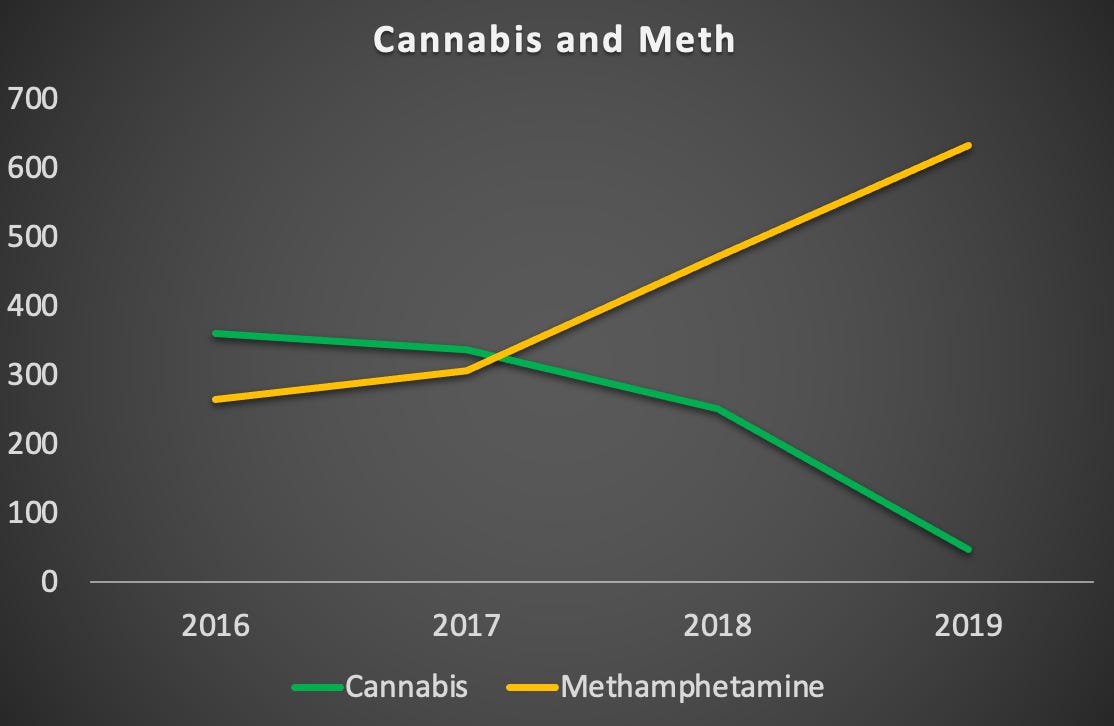

Let’s put cannabis and meth together from 2016 to 2019 to show the run-up and aftermath of cannabis legalization. it’s almost as though cannabis legalization created a vacuum for law enforcement — one that could only be filled by another drug:

Why meth?

See, the weird thing about this isn’t the meth use. Maybe people were using more at the time. Maybe it was more accessible. Maybe it was replacing other stimulant use. Maybe more folks were becoming unhoused and needing something to stay awake through the night, when it’s often unsafe to sleep.

It’s not the increase in meth use that bothers me. It’s the timing of the enforcement.

Convenient that two months after they stop busting cannabis, Calgary Police launch a huge initiative to root out this evil based on numbers not found in public reports.

Meanwhile, deaths involving fentanyl continued setting records: in 2018, an average of 56 people died each month with non-pharmaceutical opioids in their system. For meth, the average was 29 — roughly half.

If policing is about public safety, and police believe their enforcement works to reduce drug access (narrator: it doesn’t), why does meth attract so much police attention while opioid toxicities are literally killing people?

Why aren’t we defining public safety by what is killing people?