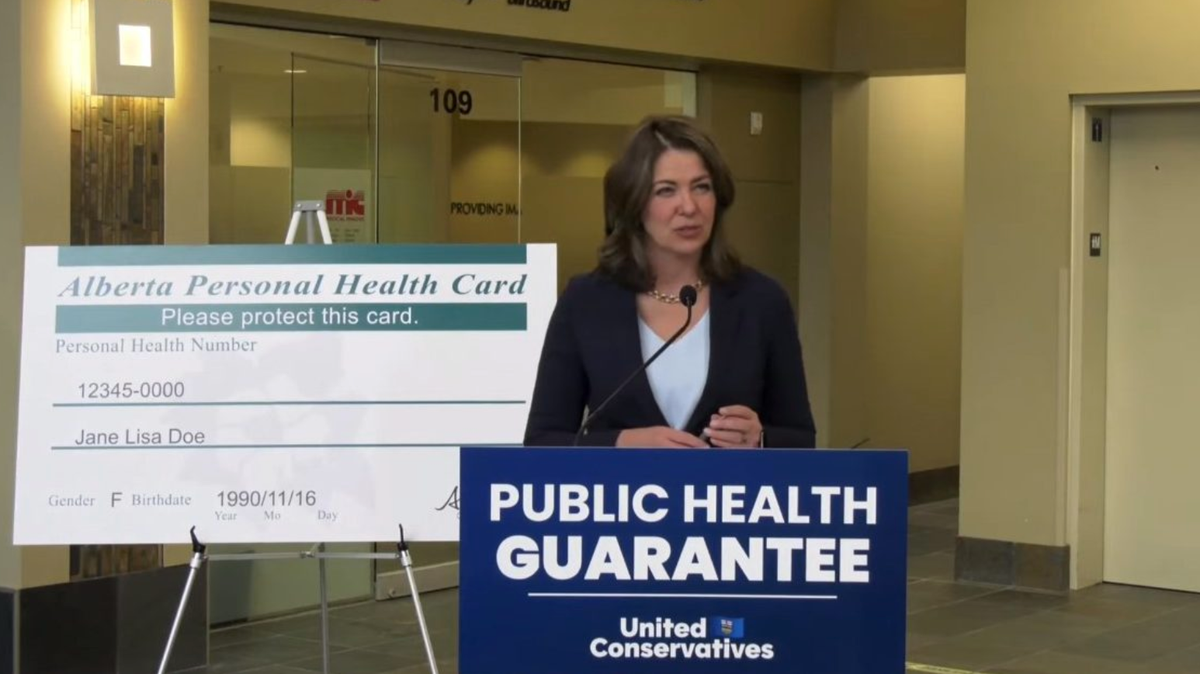

The Alberta government is privatizing recovery data

The government gave sole source contracts to a private addiction recovery house in BC for an app that obscures patient outcome data from the public, the health system and the government.

Last Door Recovery Society, a private abstinence-oriented recovery organization based in New Westminster, BC, has control of patient data from Alberta’s addiction treatment system, according to Alberta Health.

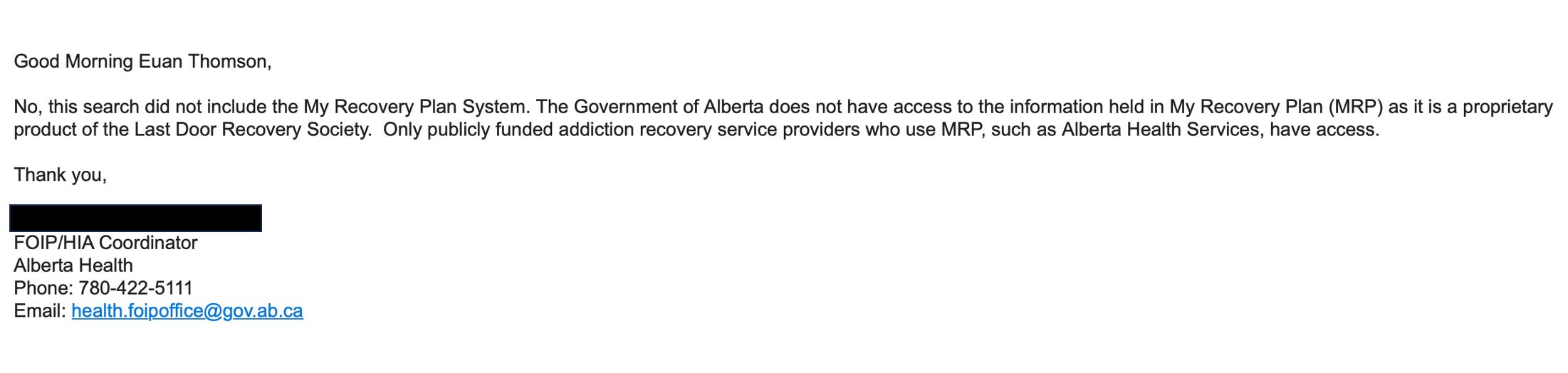

A Freedom of Information request submitted to the Alberta government’s Ministry of Mental Health & Addiction asked how many early discharges from addiction facilities occurred in Alberta from 2015 to 2023 and why people were discharged. The initial reply from the Ministry asserted that it holds “no responsive records.”

As follow-up, I asked if the search was conducted within My Recovery Plan, the government’s newly implemented system for monitoring Alberta’s so-called ‘recovery-oriented system of care.’ The Ministry responded:

"No, this search did not include the My Recovery Plan system. The Government of Alberta does not have access to the information held in My Recovery Plan (MRP) as it is a proprietary product of the Last Door Recovery Society. Only publicly funded addiction recovery service providers who use MRP, such as Alberta Health Services, have access.”

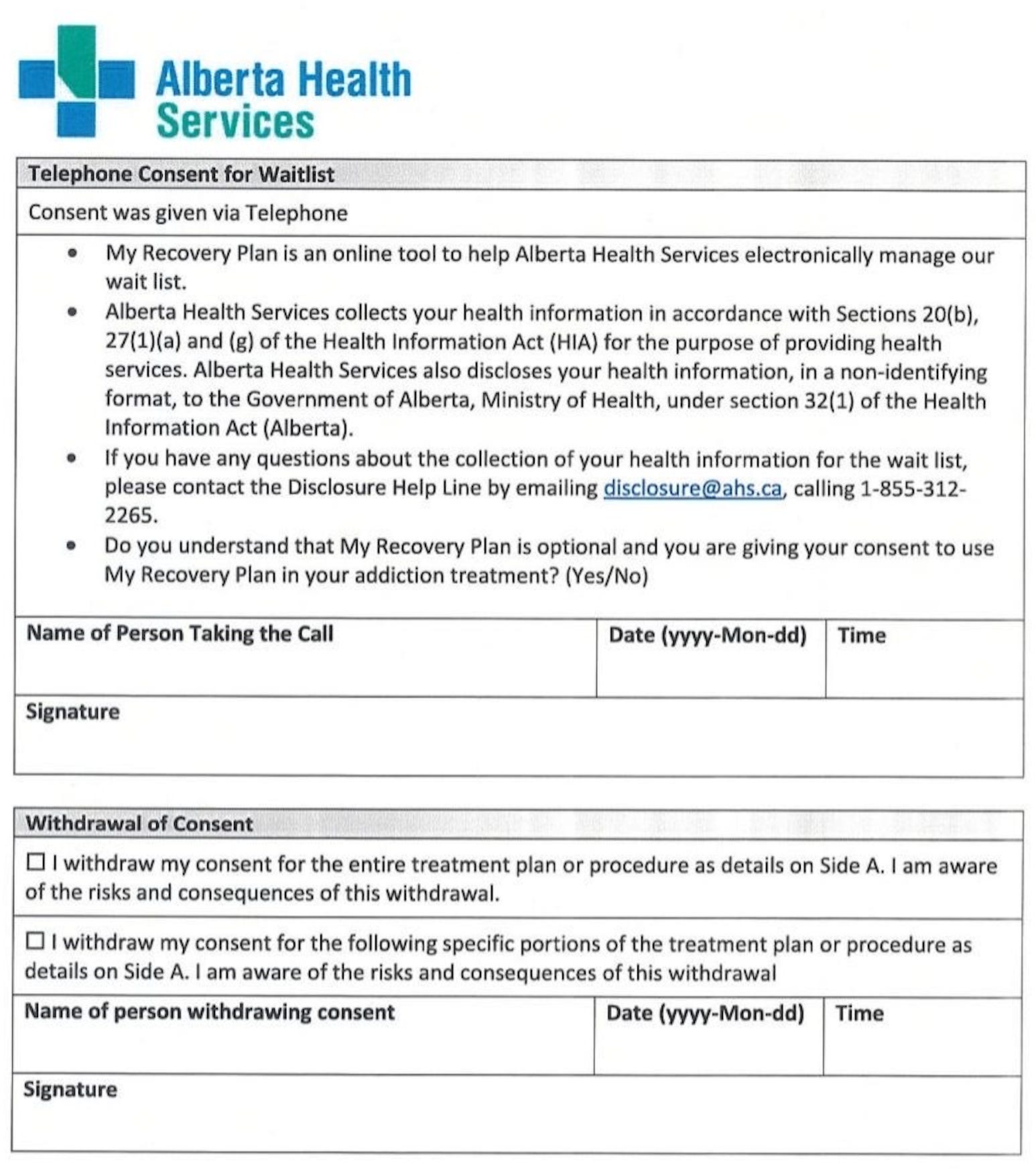

To compare this Ministry statement with the treatment facility intake process, I obtained a waitlist intake form from a detox facility run by Alberta Health Services (AHS). It details the consent process for enrolling in My Recovery Plan, and indicates that an individual's health information is provided to Alberta Health (the government ministry, distinct from AHS) in a non-identifying format. For those who decide not to share information through My Recovery Plan or not to proceed with treatment services, the form indicates “risks and consequences.”

The nature of these risks remain unclear. My follow-up question, “Do the ‘consequences of this withdrawal’ potentially include delay or withdrawal of care?” was acknowledged but not answered by Alberta Health’s FOIP office.

In parallel with the initial FOIP submission to Alberta Health, a request to Alberta Health Services did yield a list of early discharges from treatment from 2015 to 2023, but it only included AHS-run facilities. This matched the assertion from Alberta Health that individual contractors, including AHS, can only access data for their own operations.

The list shows various treatment outcomes including “Client referred out,” “Continuing treatment externally,” “Terminated by AHS,” and “Terminated by Client.” In some facilities, most early discharges are triggered by the client, but in several, the discharges by AHS consistently outweigh those by clients. Greater frequency of contract termination by AHS than by clients could indicate more stringent policies around substance use or behaviours in those facilities. Varying rules and regulations at facilities, such as allowance of opioid agonist medications like methadone, were covered in The Alberta drug model is a Christian institution.

Separate correspondence with the manager of a privately run addiction treatment facility in Alberta, who requested anonymity to protect the facility’s provincial funding, revealed that individual facilities can see numbers of people on their own wait lists in My Recovery Plan, including the number of patients uniquely on their list. However, wait lists at other facilities are centrally held in My Recovery Plan—the statement from Alberta Health strongly suggests this is visible in full only to Last Door Recovery.

According to this facility manager, My Recovery Plan was implemented to provide Alberta Health with a clearer picture of treatment demand. It remains to be determined if Alberta Health has access to these data, given that it does not have access to patient outcome data related to early discharge.

If neither the Alberta government nor the general public have line of sight on these data that are generated through considerable public subsidies of private treatment, it is difficult to comprehend their public benefit. Privately run treatment spaces in the province comprise a growing majority of the province’s addiction treatment capacity. Centralizing their discharge practices in private hands could obscure motivations for facilities to discharge patients that are rooted in profit, not patient care.

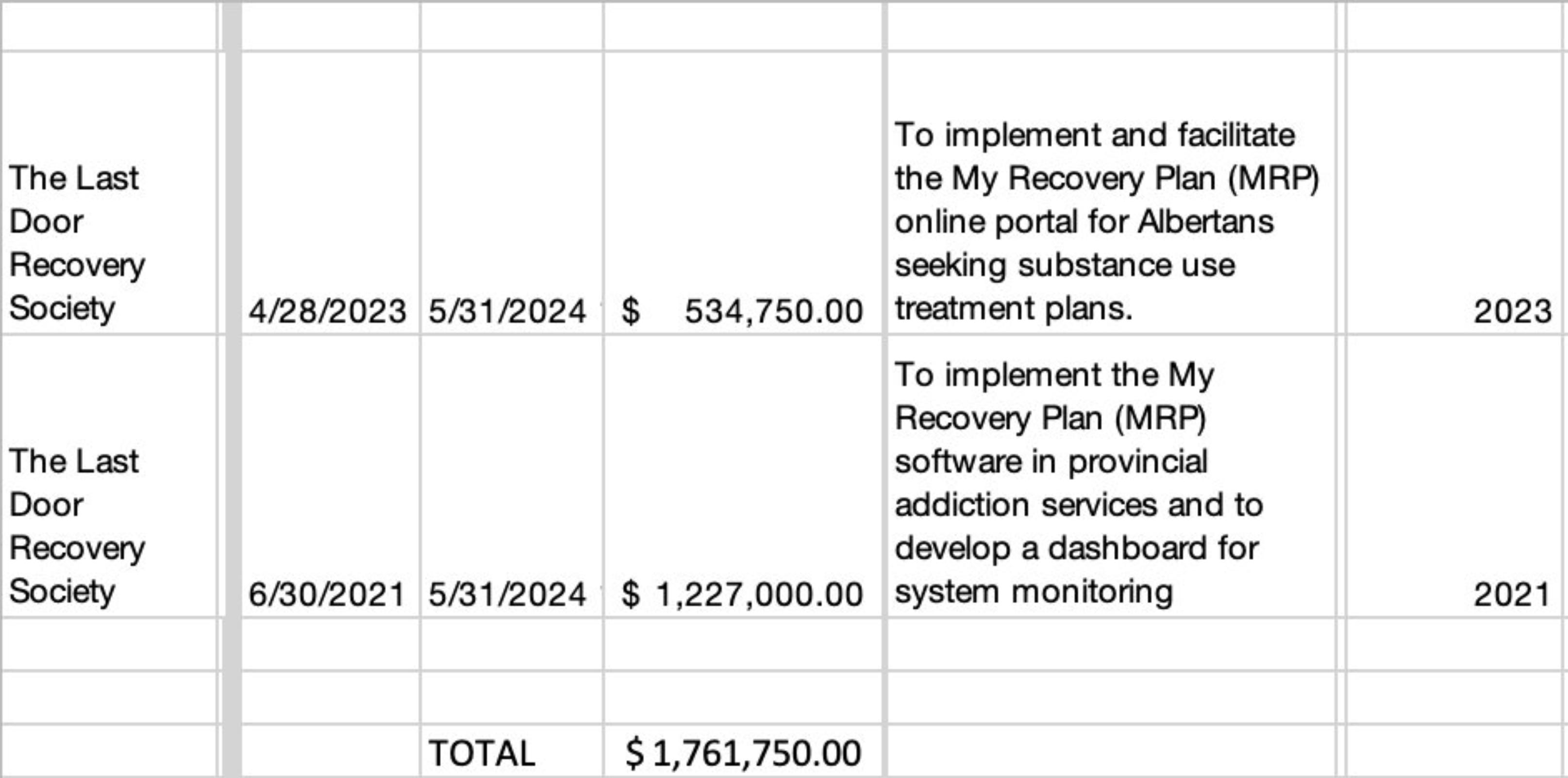

Starting in June 2021, the Alberta government provided sole source contracts totalling $1,761,750 to Last Door Recovery for My Recovery Plan. The first contract disclosure states that Last Door would “develop a dashboard for system monitoring.” However, the second contract drops the term “system monitoring,” specifying instead an “online portal for Albertans seeking substance use treatment plans.” This discrepancy suggests that if plans existed to publicly disclose evaluation metrics on treatment, such as reasons for early discharge, they may have been abandoned in the period between the two contracts.

Reporting in February 2023 described MRP as “an online tool that tracks waitlists, site capacities and outcomes for clients.” In the same article, an interview with the premier’s chief of staff, Marshall Smith, said MRP would mean the government wouldn't have to “phone around from service provider to service provider and ask them to estimate how many people they have on their [waiting] list.”

Last Door Recovery currently has no treatment facilities in Alberta, but does enlist patients for its New Westminster facility through its downtown Calgary recruitment centre. The New Westminster facility has been under fire since February 2023 for sexual assault charges laid against a longtime contractor at the facility, as well as alleged silencing by senior staff at the organization of people raising concerns about abuse.

Drug Data Decoded has previously discussed ties between Last Door and the Alberta government. The premier’s current chief of staff, Marshall Smith, served as chief of staff in the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction when the first of these sole source contracts was secured with Last Door. Before that, he was president of the Canadian Addiction Counsellors Certification Federation (CACCF), where Last Door held representation through its Director of Operations Jessica Cooksey, who served as chair of the CACCF Recovery Coach Credentialing Committee. Cooksey made news in January 2023—ten days before the sexual assault allegations surfaced—decrying her as-yet unverified allegation of minors accessing safe supply from MySafe prescription access machines.

(In September 2023, a review of 142 unregulated drug toxicity deaths of minors in B.C. from 2017-2022 by the BC Coroner demonstrated no evidence that youth drug poisoning deaths are driven by safe supply hydromorphone. In June 2023, BC representative for children and youth Jennifer Charlesworth said there is no indication that youth are even accessing diverted safe supply, though it seems likely enough that regulated hydromorphone could be diverted from programs and accessed by youth through street vending. The bigger question is whether the public can accept this as being safer than unregulated fentanyl.)

Meanwhile, Last Door’s Giuseppe Ganci chairs Recovery Capital Conference of Canada, which returns to Calgary on April 2-3 and is certain to be sponsored and well attended by the Alberta government. Ganci was approached for comment on the Alberta government’s statement six hours before publication of this piece.

The revolving door

To understand why transparency on early discharge is critical, two addiction medicine specialists were asked for their views. Both individuals also feared government reprisal and requested anonymity. They indicated that the key concern is increased risk of death: patients in treatment for opioid use are highly likely to resume use but, as a result of treatment, have lower tolerance to opioids. Given that many people are sent to facilities in unfamiliar locations, there is a high chance of being discharged into an environment with little safety and few connections.

Early discharge could be leveraged as a mechanism to create ‘revolving door’ clients, while influencing program statistics for a program—particularly in Alberta, where ‘recovery capital’ scores are the predominant measure of success for these treatment programs. Contrasting this scenario, early discharge could also be leveraged as a threat, when people are told they must complete a program to see their kids again, avoid jail, or regain employment. It’s critical to standardize the reasons for early discharge to ensure equity in access to care.

Finally, these services should be responsible for the safety of people that come through their doors—in this context, that their discharge includes access to medication or other services. Obscuring reasons for discharge means the professionals on the receiving end have no starting point to tailor their services and ensure people’s unique needs are met.

As one specialist told us, “if you claim to ‘treat addiction,’ how can you kick people out who are struggling with addiction for having an addiction?”

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis on topics concerning the war on drugs using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.