Drug inhalation is being choked off in Alberta

Demand continues to increase dramatically for clean drug inhalation supplies, but procurement data obtained by Drug Data Decoded show the supply is being throttled back. Is the shortfall helping to drive Alberta cities to new overdose heights?

A shortage of glass pipes for drug inhalation is creating chaos in Alberta as demand outpaces the government's willingness to fund them, according to sources inside health agencies and data obtained through a freedom of information request by Drug Data Decoded.

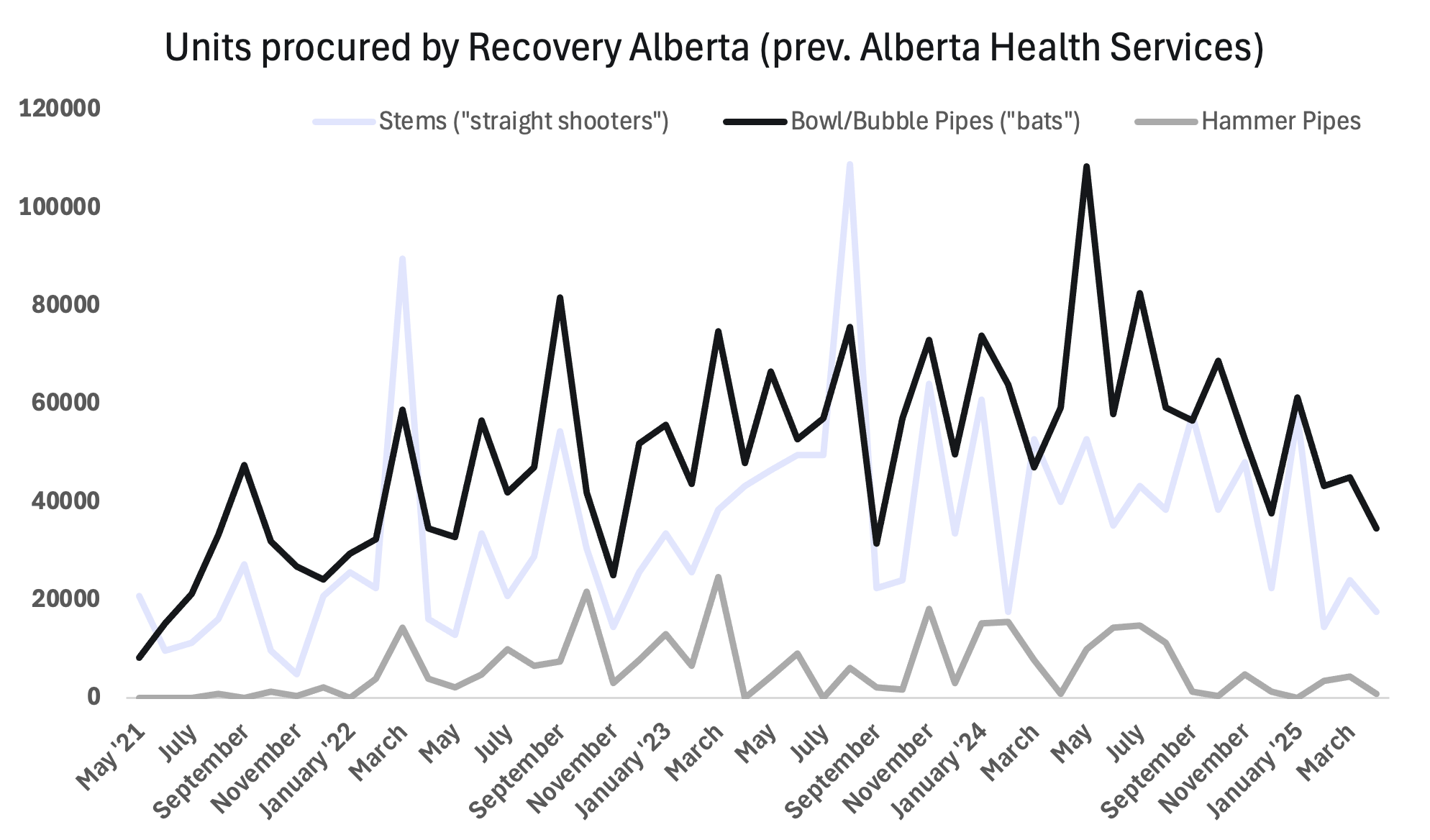

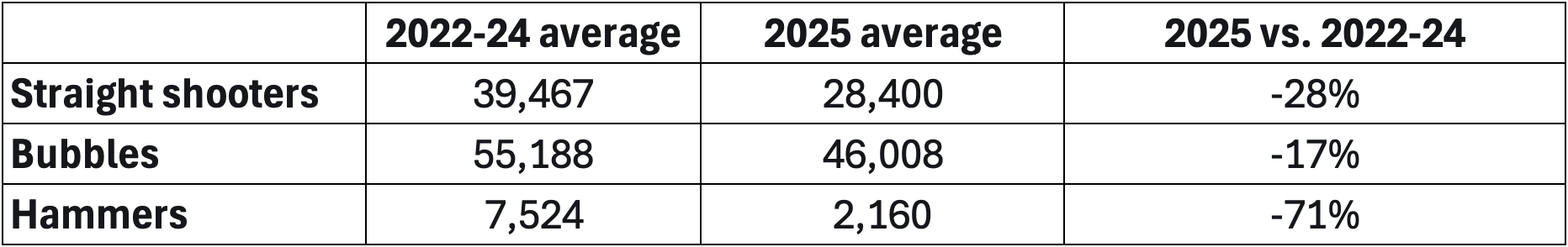

The data show that monthly procurement by Recovery Alberta, which oversees a large portion of the supply, is down across three styles of glass pipe by 17 to 71 per cent when comparing the average from January to April 2025 with the monthly average across 2022-2024.

Street outreach teams in Calgary and Edmonton were asked by Drug Data Decoded if procurement shortages were affecting their ability to operate. They insisted they have been struggling for months to obtain enough glass pipes to meet demand.

Patty Wilson, a Calgary-based nurse practitioner who works with people who use drugs, frequently hears from frontline workers having trouble finding enough of these supplies – and some are having to pay for them out of pocket.

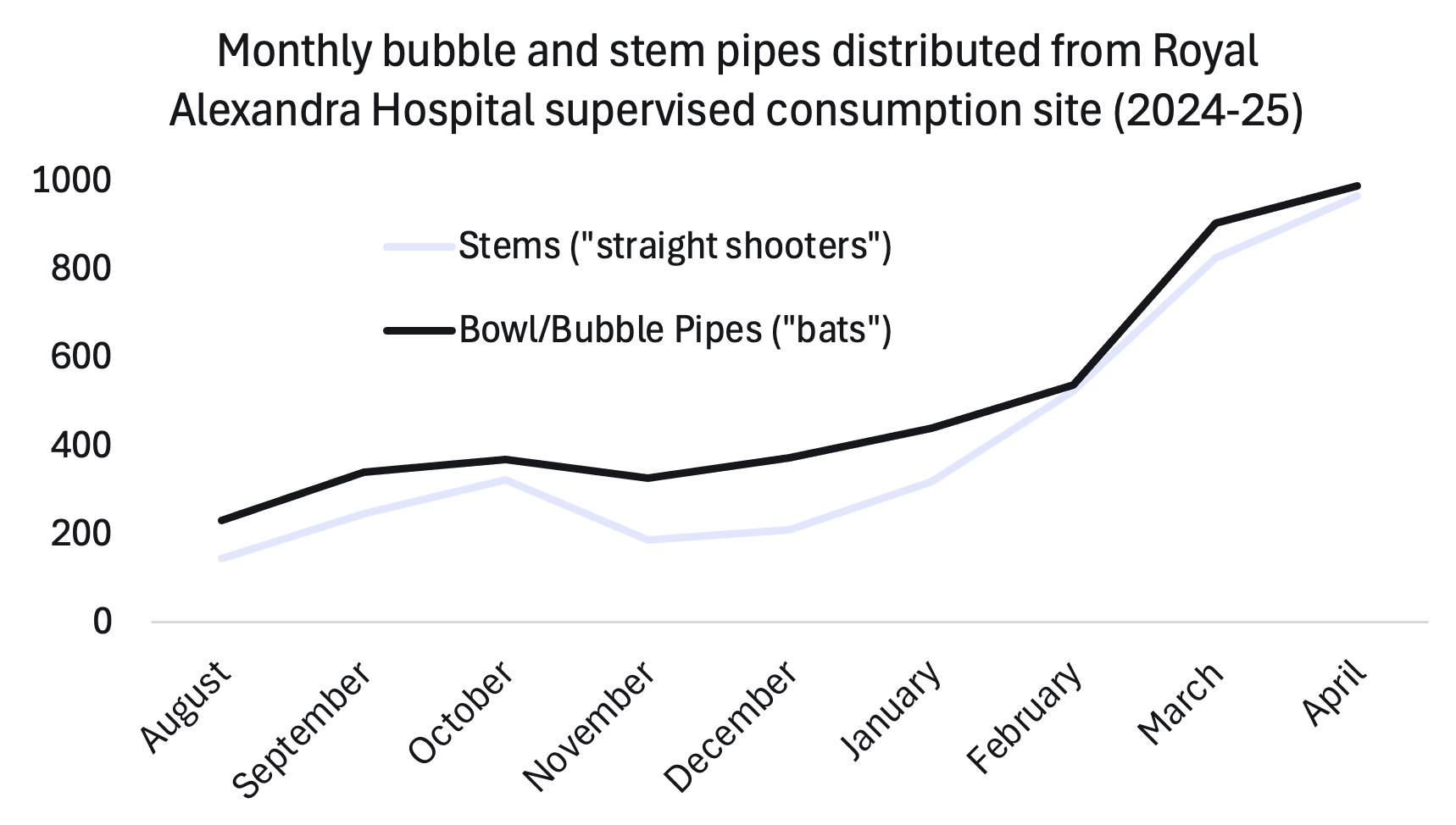

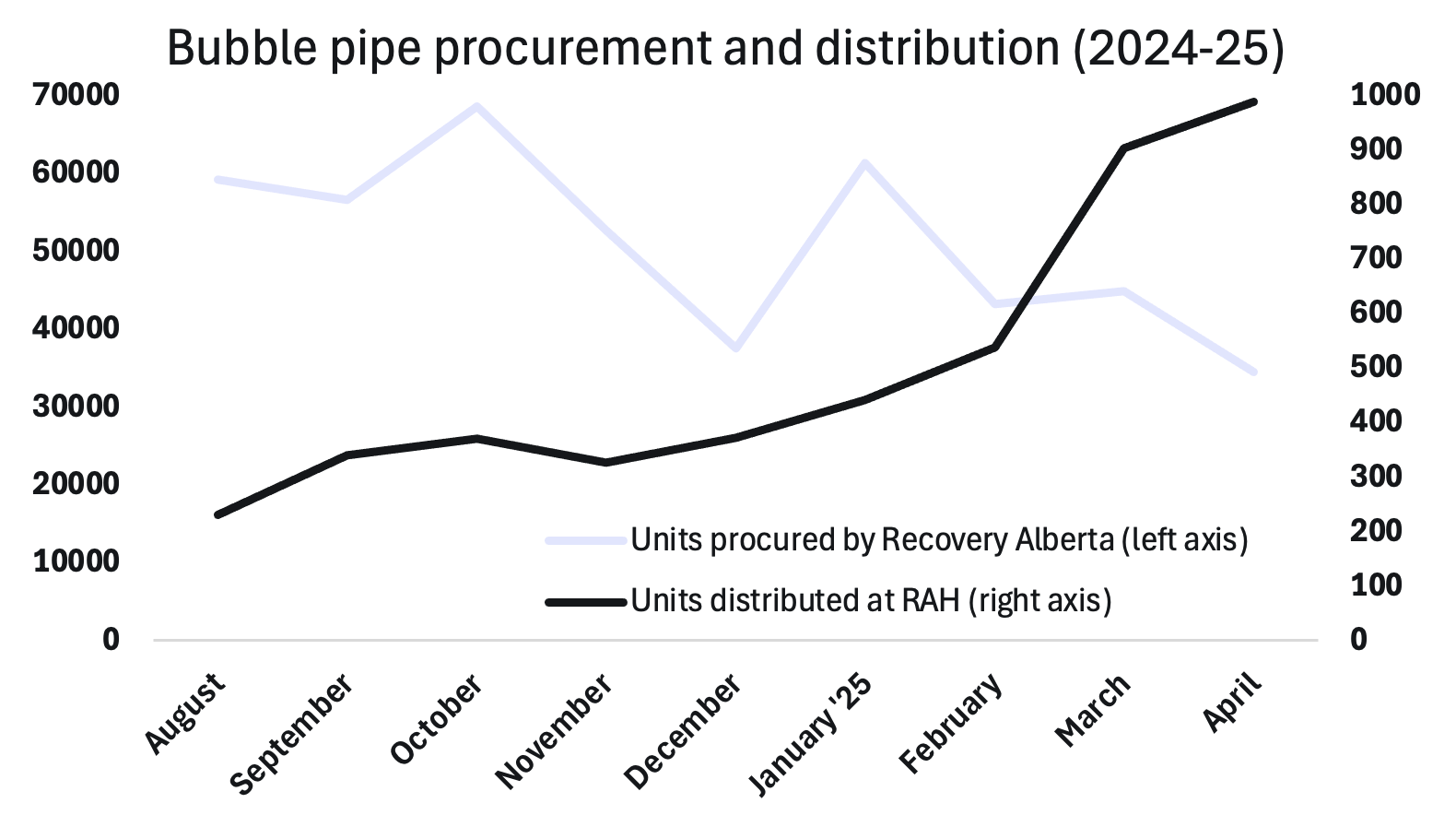

The data obtained from Recovery Alberta show that distribution of stem and bubble pipes at Edmonton's Royal Alexandra Hospital-based supervised consumption site (SCS) increased roughly five-fold since August 2024, when the site began recording distribution volumes. No other distribution data were provided by Recovery Alberta.

Comparing the provincial procurement of bubble pipes with their distribution at the SCS over the same time period shows that while demand was clearly increasing in this location, overall procurement by Recovery Alberta was steadily declining. The same pattern holds for straight shooter (stem) pipes.

Recovery Alberta and the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction were asked if procurement cutbacks were deliberate, and if they were the result of a political decision by the Alberta government. The Ministry did not respond, but Recovery Alberta replied that organizations "requiring additional inhalation or injection supplies are able to acquire them as needed."

According to several sources, this is not the full story. Two workers at different organizations told Drug Data Decoded on condition of anonymity that the provincial budget for these supplies is far too low to meet demand. But when it was asked to adjust the funding to reflect high demand, the sources say the government refused.

A 2020 Alberta government mortality report that was forced into the public sphere by a previous Drug Data Decoded investigation showed that tools for inhalation drug use are discovered near overdose fatalities 3.5 times more often than tools for injection. This means inhalation drug use should be a critical target for reducing overdose risks.

According to Wilson, a shortage of glass pipes forces people to share instead of having their own. While this facilitates infectious disease transmission, including hepatitis C, it also increases the risk of overdose and other harms.

As a Calgary-based street outreach worker explained to Drug Data Decoded:

"Someone might smoke down [opioids] and then use the same pipe to share side [methamphetamine] with a homie who doesn't smoke down, and then we've got a homie dropping... It's entirely avoidable."

The outreach worker also expects to see increases in "demand for [injection] rigs, makeshift smoking devices that are less safe than fresh pipes, and more people shooting up," as a result of the cutbacks.

Public health reports have repeatedly emphasized that people who use drugs have shifted toward inhalation rather than injection. As early as 2017, British Columbia was reporting that more than half of overdose fatalities followed inhalation.

Research by Matt Bonn, Thomas Kerr and Andrew Ivins suggests this shift was in part a consequence of fentanyl injection causing greater damage to people's veins. As a short-lasting painkiller, fentanyl demands much more frequent dosing than heroin, which dominated the unregulated opioid market until fentanyl replaced it.

One study participant told the research team that "you can’t find my veins anymore. I’ve killed all my veins."

Victoria-based frontline worker Juls Budau insists that "providing pipes reduces syringe circulation and litter, as each pipe easily replaces 50-100 syringes." Budau has responded to overdoses that occurred after someone accidentally inhaled fentanyl vapour when attempting to use methamphetamine. She also points to research showing that distributing clean pipes increases engagement with health and recovery services and decreases lung damage by reducing the need to rely on the "makeshift smoking devices" described by the unnamed Calgary-based worker.

Glass pipes tend to be thin-walled for rapid heat transfer. Expecting breakage, people encountered by street outreach workers often request more than one pipe. A comparison of these three pipe styles was published by Filter Magazine in 2019 and focused on the innovative hammer pipe, but for most cities in Alberta, the bubble remains the most requested – and most breakable.

As the outreach worker explained, "we're literally rationing bubbles."

The reduction in pipes currently reduces up-front monthly costs by $18,161, but pipe sharing is expected to drive higher viral transmission. The medication for a single course of hepatitis C treatment was listed at $41,188 in 2019.

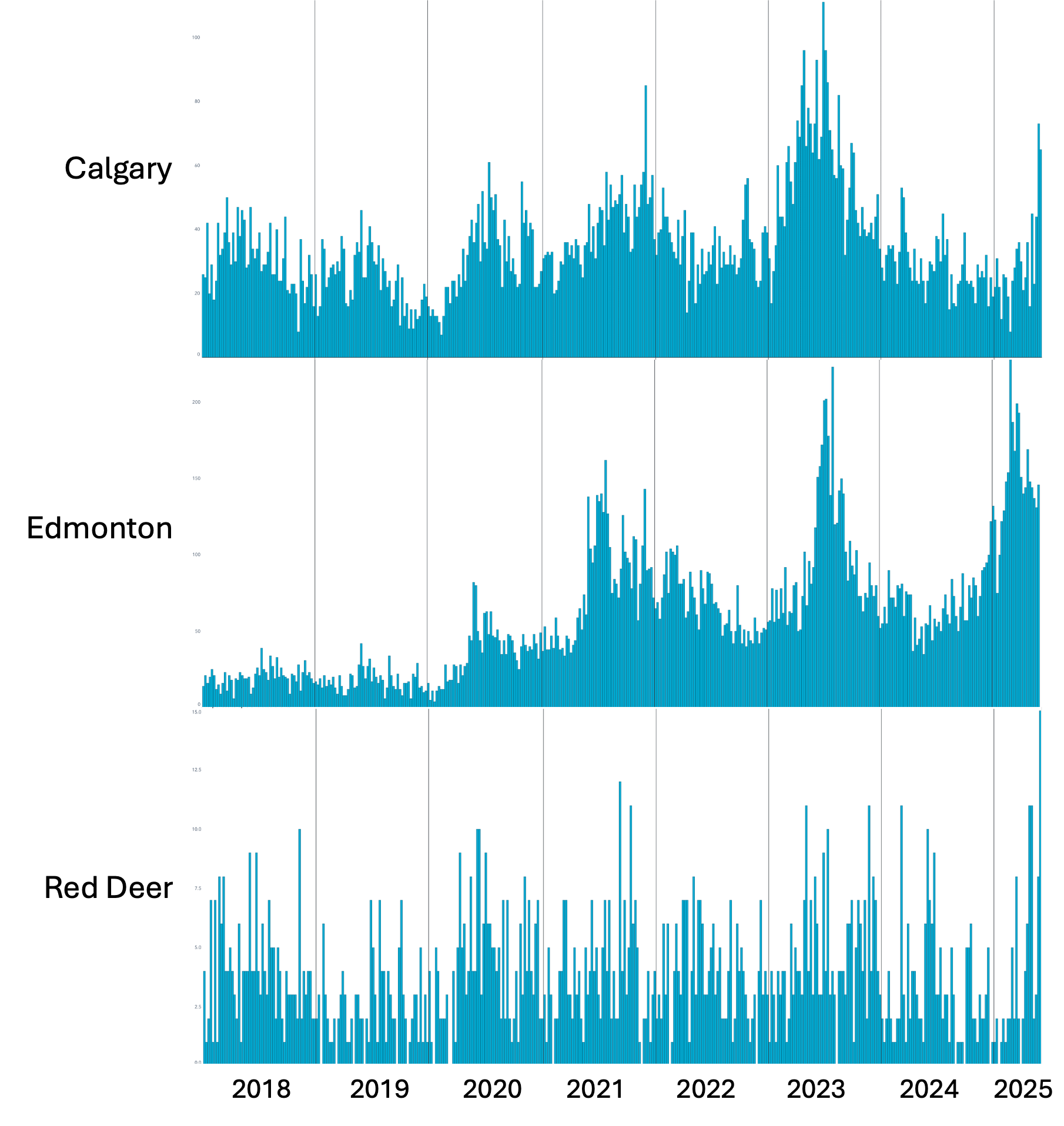

The shortage of harm-reduction tools comes at a moment when Edmonton and Red Deer are setting records for weekly EMS dispatches to opioid overdoses, and Calgary is rapidly climbing toward its 2023 highs. EMS dispatches are closely associated with overdose fatalities, which take several months to be made public as preliminary data and many months beyond that to be accurate.

Notably, Red Deer EMS dispatches have reached all-time highs ever since the city's only overdose prevention site was closed by the United Conservative government after the city council voted to request its closure. At the time of that vote, Red Deer mayor Ken Johnston declared it a "city of recovery."

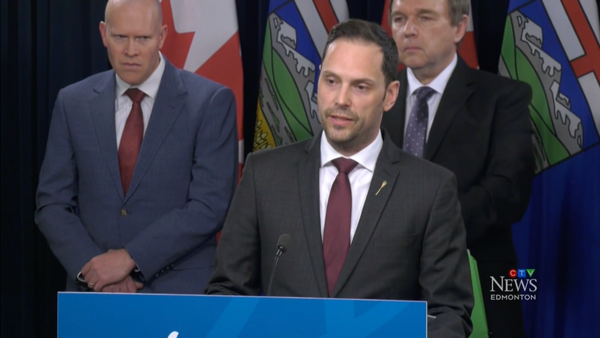

The province-wide disruption in glass pipe supply follows loud backlash from the government against public provision of harm-reduction resources. In late 2023, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith threatened to pull funding from SafeLink after learning that the organization provided education materials on safer drug inhalation practices to high school students in Medicine Hat.

At least 108 high school-aged people in Alberta died of overdose from 2022 to 2025. The Public Health Agency of Canada's guidelines for reducing substance-related harm among youths steer educators away from zero tolerance policies and abstinence-only education in schools, emphasizing instead the value of evidence-based substance use education, building positive environments and ensuring social and health equity.

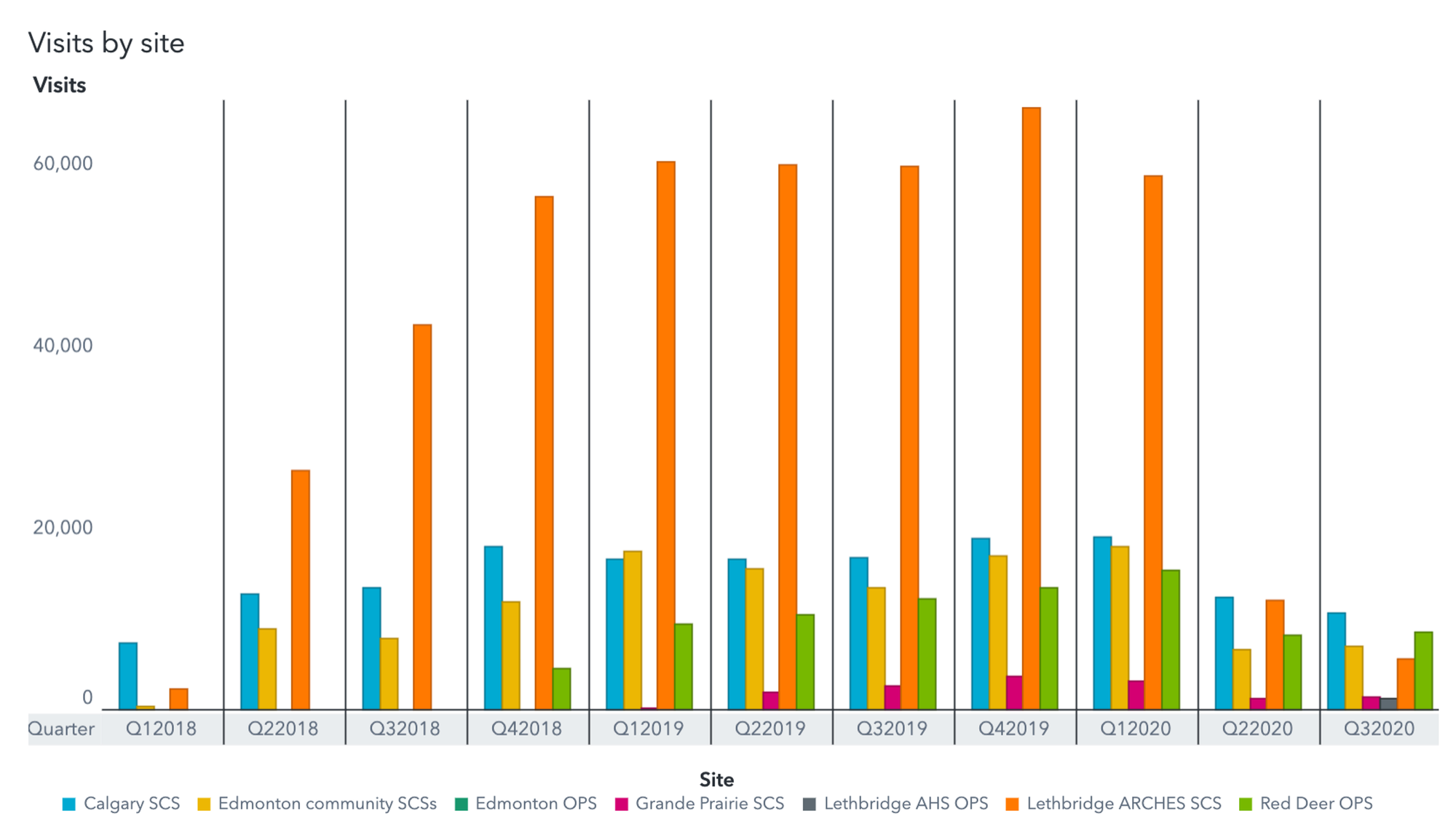

For adults who inhale drugs, options for risk mitigation are also being limited. The only site for supervised inhalation of drugs in Alberta was located in Lethbridge, but the United Conservative government defunded it in 2020. Until then, it was the busiest SCS in the country, with total visits outpacing other sites in Alberta nearly four-fold.

Five years after the Lethbridge inhalation site was closed, political motivation to choke off inhalation supplies can be situated within a broader strategy. As consumption behaviours evolved with the new reality of fentanyl, right-wing demonizing of injection was a red herring to consume public attention. Meanwhile, a covert war was waged against inhalation resources to force the most vulnerable people who use drugs into a prisoner's dilemma: get sober or get dead.

With Alberta now set up to sacrifice these humans to its publicly funded but privately profitable recovery sector, that strategy has worked as intended.

Data from the freedom of information response can be viewed here. Media are welcome to request spreadsheet versions by emailing info@drugdatadecoded.ca.

If you have additional information on this story, please get in touch at info@drugdatadecoded.ca.

An early version of this story was shared with Paid subscribers on the evening of June 6 and the public version was released on June 9, 2025.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.