RECLAIM Collective speaks out against forced abstinence

In advance of Support. Don't Punish on June 26, the founders of RECLAIM Collective share their thoughts on how the forced abstinence legislation recently passed by the Alberta government will impact their community.

RECLAIM Collective conducts consulting, speaking, training, research and organizing related to substance use. Contact them today or register for their Support. Don’t Punish online event on June 24.

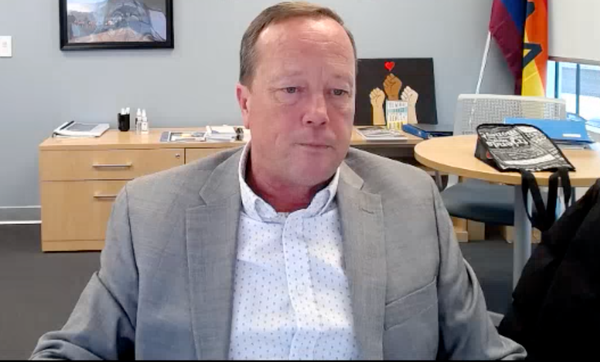

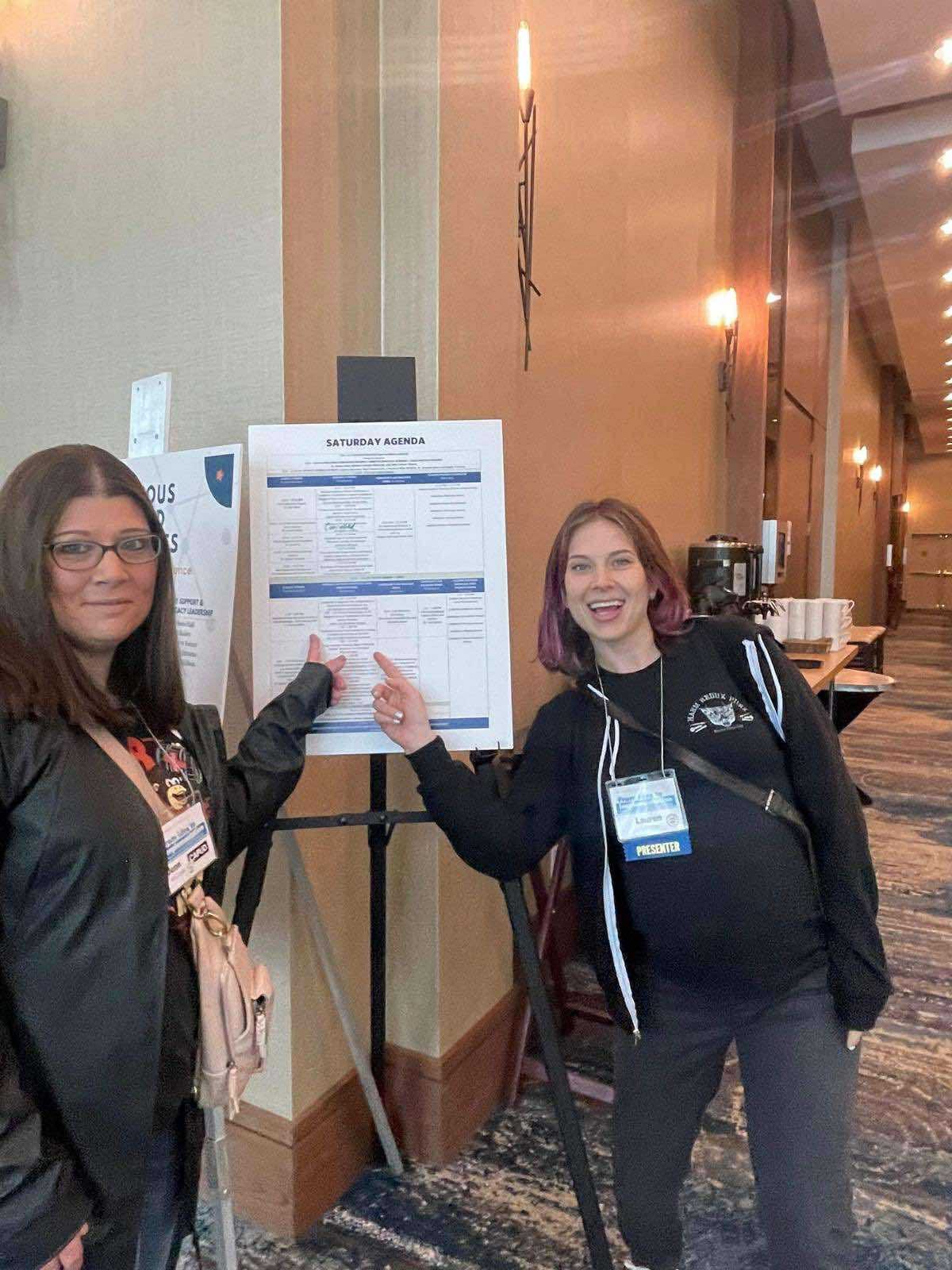

Lauren Cameron

Disconnected in Youth, Finding Myself in Drug Use

When I was twelve, my conservative Christian mother forced me into juvenile detention. She charged me with assault for kicking my dad when they tried to stop me from leaving the house, mischief under $5,000 for punching a hole in my own bedroom wall, and underage drinking. That led to probation and house arrest. I kept breaching my 7PM curfew, and every time, my mom called the cops. They'd arrest me and throw me in adult lock-up until finally, I ended up doing three months in juvenile detention in Nova Scotia.

Working in frontline harm reduction, you understand what meeting people where they’re at really means, especially when you’ve been there yourself – when you’ve felt that pressure to go to treatment or to recover because everyone says that’s what you should do, even when you’re not ready. I’ve been there. At my most chaotic point, I cut off all my natural supports, not because I didn’t care, but because the stigma around my drug use created a shame so deep it made me want to disappear.

That shame didn’t bring me closer to help. It pushed me away from health care, from people, from support.

If I had been forced into treatment during the era of my most problematic drug use, it would not have worked. Emotionally, mentally, physically – I wasn't ready for change. Drugs were the only thing that made sense to me. They were the only connection I had that didn’t let me down. That connection was harmful. It was trauma-based. And I knew that, even then. But it didn’t matter. What mattered was that I had the freedom to make my own choices. Everything else in my life felt out of my control. Drugs saved my life in that sense. Taking away that last bit of freedom would have felt like a prison sentence. I would have spent every single day counting down to when I could get out and use again.

People who use drugs know the risks. We know that after even a short time away, your tolerance drops. If you use the same amount after getting out of treatment, you can overdose and die. That is not a theory, it is science. When policymakers ignore that, it becomes clear they are not trying to keep us alive. Instead, they are deciding who is worth saving and who can be left behind: the strong survive, and the rest of us don’t matter.

And we need to be honest about who this impacts the most. A disproportionate number of unhoused people are Indigenous. And now with forced treatment in Alberta, people are being stolen from the only communities they have – their street families, their chosen families – then thrown into 12-Step abstinence programs based in white Christian values. People are saying it feels like residential schools all over again. Once again, the government and police are deciding what is best for Indigenous people. Once again, they are removing people from their communities "for their own good."

Coordinating street outreach peer navigators in Calgary, one of our strongest beliefs was self-determination. You can't force someone into recovery and expect it to stick. Coercion does not motivate, it pushes people further away. Taking away someone’s autonomy is a form of trauma.

What we’re seeing on the streets already is a fear of doctors and healthcare. Forced treatment will scare socially marginalized people even more. If you need to get an infection checked out but are afraid of being locked up for your substance use, then you're not going to bother out of fear of being locked up in detox and rehab. People won't just die from so-called compassionate intervention, they’ll also die from fear of getting help for their medical issues.

My experience in juvenile detention didn’t "scare me straight." It just shaped how I saw myself. I wasn’t some hardened criminal, I was a messed up kid with unmet needs – but being locked up made me feel like a criminal. It gave me more connections with people who used drugs, and by age fourteen I’d already run away from home to avoid getting forced into treatment or locked up again for breaches. That’s when I found a different kind of community, on the street, with people who used. That’s where I felt seen, even if it came with substances.

Being criminalized so young deeply traumatized me. It pushed me further into heroin and cocaine use, which eventually became problematic. What I needed wasn’t jail or forced treatment or being sent to some Christian camp as part of my probation. What I needed was autonomy, someone to ask what was going on, and not punish me for it.

The Compassionate Intervention Act is just another version of the same old thing. They say it’s about help, but it’s really about control. Forcing someone into treatment is not care, it’s harm.

I never went to 12-step because I knew right away it was a religious program. Starting with the Lord’s Prayer? That told me all I needed to know.

Andrzej Celinski

Treatment Must Be Intentional

In my experience, and from what I have seen others experience, being forced into treatment through drug diversion courts or other elements of the criminal justice system, or being heavily coerced or pressured into treatment by friends, family or systemic intervention is a counterproductive approach. When someone is not ready for treatment or does not choose to go willingly, their chances of success are greatly diminished.

But this is not the greatest harm, nor the most dangerous or unethical aspect of such practices. It is well documented that people are far more likely to have a negative experience in treatment, continue using substances after release, and face other adverse outcomes when forced or pressured into treatment. Those who spend anywhere from a weekend to a year in treatment often leave vulnerable to reduced tolerance, which significantly increases their risk of overdose.

Both research and lived experience show that voluntary engagement in treatment is more likely to lead to positive outcomes. While coerced treatment may result in short-term compliance, it often fails to address the underlying causes of distress. If someone truly wants or needs to use, for example due to the intense pain and suffering of physical withdrawal depending on the substance and their level of tolerance, they will likely find a way to do so.

In many cases, coercive treatment can create or reinforce trauma, especially for individuals with a history of abuse, neglect, systemic oppression, or other forms of psychological, emotional or intergenerational trauma. Being forced into treatment without consent or readiness can mirror earlier experiences of lost autonomy, leading to re-traumatization. For those who have faced discrimination or unstable environments like poverty, incarceration, or involvement with the child welfare system, coercive approaches can deepen feelings of powerlessness and mistrust, making recovery even more difficult. Instead of fostering a sense of safety and agency, involuntary treatment can mirror the dynamics of control and powerlessness that contributed to a person’s struggles in the first place.

While the intent behind involuntary treatment may be to protect individuals from harm or address urgent crises, the experience of coercion can cause lasting emotional damage, erode trust in healthcare systems, and even reduce the likelihood of recovery. When people are compelled to enter treatment against their will, they are stripped of their autonomy and dignity which are both critical components of effective recovery.

Recovery must be viewed along a continuum of care. In my experience, abstinence-based programs, by their nature and structure, often lack an understanding of the realities of substance use. These programs can be dogmatic, and I have seen firsthand that those who appear to be ‘working the program’ without questioning any aspect of their treatment are often the ones at greatest risk when they leave. They may have simply been following the leader in a cult-like environment without critically examining their relationship with substances or making realistic, attainable choices. Taking the time to be intentional leads to better outcomes for both individuals and society.

There are also significant legal and human rights implications. In some jurisdictions, people can be detained and medicated without consent, based on broad or vague criteria. This raises the risk of misuse, misdiagnosis, and the disproportionate targeting of vulnerable populations such as those experiencing homelessness, poverty, or racial discrimination. For treatment to be truly ethical and effective, it must prioritize informed consent, mutual respect, and the recognition of each person’s right to actively participate in decisions about their own care.

Jenn McCrindle

Forced Treatment Will Deepen Distrust

I acknowledge that I am fortunate to never have experienced any coercive or forced care. Today, I attribute the fact that I am able to lead a relatively stable life now as a parent, frontline worker and person who is largely “in recovery,” to my autonomy in decision-making.

As I sought out and utilized more harm reduction supports, I became more prepared and confident in whatever “next step” was coming – empowered, as it was meant to be in the harm reduction movement's philosophy. A team of wonderful health care providers trusted my capabilities to choose how I wanted to continue on opioid agonists, whether I was trying to decrease my dose or needing to raise it a little sometimes. The point was that I had more than an opinion in my treatment, I had the final say. And it was life changing.

I am a rebellious soul and can attest that anything forced or against my will would not have worked. My resentment at the systems at play would cause isolation, certainly not a willingness to ask for support or help addressing my substance use.

These days, I contend with a problem I haven’t met before in my Outreach role. I’ve always encouraged the people I work with to advocate for themselves in medical situations for example, or to be really honest with their provider about how they are functioning on their dose. It used to feel safer to do so.

But when the threat of several authority bodies that can apply to have you detained for an unknown amount of time and forcefully administer procedures or medication you haven’t consented to, it makes you want to avoid bringing any attention onto yourself. You will be viewed as drug-seeking or problematic. These could easily form the “reasons” for a provider or an authority to deem you incapable of caring for yourself.

Spaces for people to access help for their substance use, or with health concerns need to be non-judgmental and person centred to be considered effective. Punitive repercussions for having a bad day or being houseless and visible to the public will not solve the complex issue of substance use, we know this. Empowering people, walking beside them as they are and encouraging every positive step along the way – that creates change.

Tonya Evans

Treatment Only Worked When I Was Ready

My experience with involuntary treatment taught me something that many people still don’t understand: you can’t force someone into ‘recovery’ before they’re ready. I was ordered into treatment by Family and Children’s Services, with the condition that if I didn’t comply, I would lose access to my son. At that point in my life, I wasn’t ready for treatment.

But, out of fear of losing my child, I ended up going through two different detox programs and two separate treatment centres.

While some aspects of those programs were helpful, they didn’t address the deep trauma that had led me to use substances in the first place. As a result, I wasn’t able to stay abstinent. In fact, being forced into treatment before I was emotionally ready left me feeling even more isolated. I felt like a failure, as if nothing could help me.

What people often overlook is that attending "treatment," often referred to as recovery, should never be framed in a punitive way such as offering someone the choice between jail or rehab. Instead, recovery should be approached through the lens of harm reduction and providing individualized, person-centred care. This means recognizing that healing is an ongoing process that must come from within. For me, healing required a holistic approach to wellness, but it will take a different shape for everyone.

Coerced treatment didn’t lead to lasting change for me. It wasn’t until I made the voluntary decision to seek help that things began to shift. When I chose recovery on my own terms, I was finally able to confront the underlying issues, fully engage in the process, and start rebuilding my life.

My story is not unique. Countless people who use substances are pushed into treatment through threats, fear, or the condition that if they do not go, their children, homes, or freedom could be taken from them. This isn’t justice, and it’s not supportive. Rather it is punishment disguised as care.

Real change happens when we treat people with dignity and compassion, not coercion. We need trauma-informed, voluntary support systems that meet people where they are, not systems that force them into boxes they’re not ready to fit into. Only then can we begin to truly help, not harm.

Check out RECLAIM Collective for consulting, speaking, training, research and organizing related to substance use.

This piece is not an advertisement. Drug Data Decoded freely endorses the work of RECLAIM Collective, which has been lauded by researchers, organizations and individuals across the country.

Register for RECLAIM's Support. Don’t Punish online event on June 24 as well as the June 26 online event co-hosted by Harm Reduction Action Collective and HIV Legal Network.