Marshall Smith's propaganda rampage

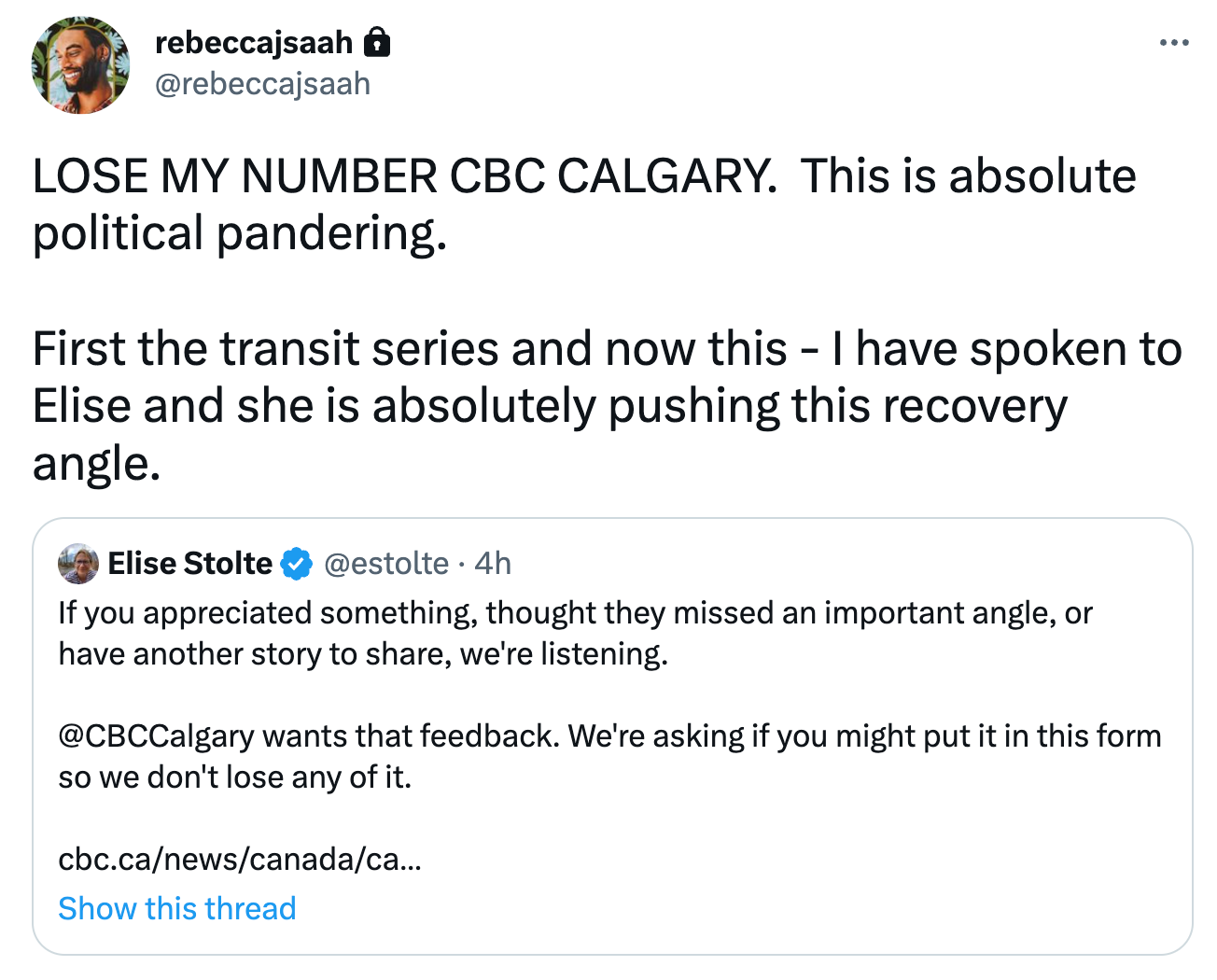

CBC Calgary provides lovely background music to unending UCP overtures to abstinence-based treatment. But can violins clash with critical analysis?

Over this morning’s public airwaves, you may have been ushered through a virtual tour of Alberta’s newest “therapeutic community,” accentuated by soothing violin and piano instrumentals.

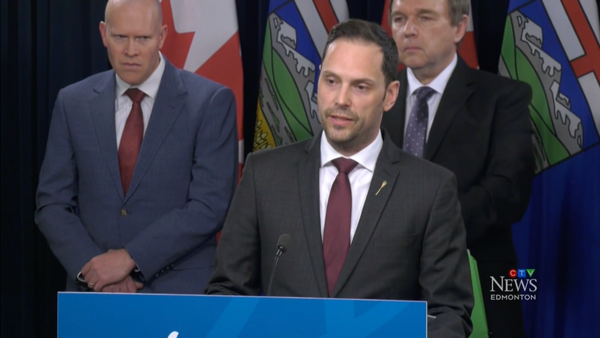

In a piece titled “The Way Out: Addiction in Alberta,” which promises a full week of content, Marshall Smith, Premier Danielle Smith's Chief of staff, offered his take on the soon-to-open Red Deer Recovery Community. The facility marks an apparent “sea change” in Alberta’s approach to substance use. Marshall Smith emphasizes that “the goal of treatment is to get clients off of drugs — it’s to inspire them to live a drug-free life.”

Marshall Smith is on a propaganda rampage. And for good reason: the UCP have been cooking the numbers on overdose mortalities in Alberta as we run full-speed into another spike in overdoses.

CBC should learn how to forecast

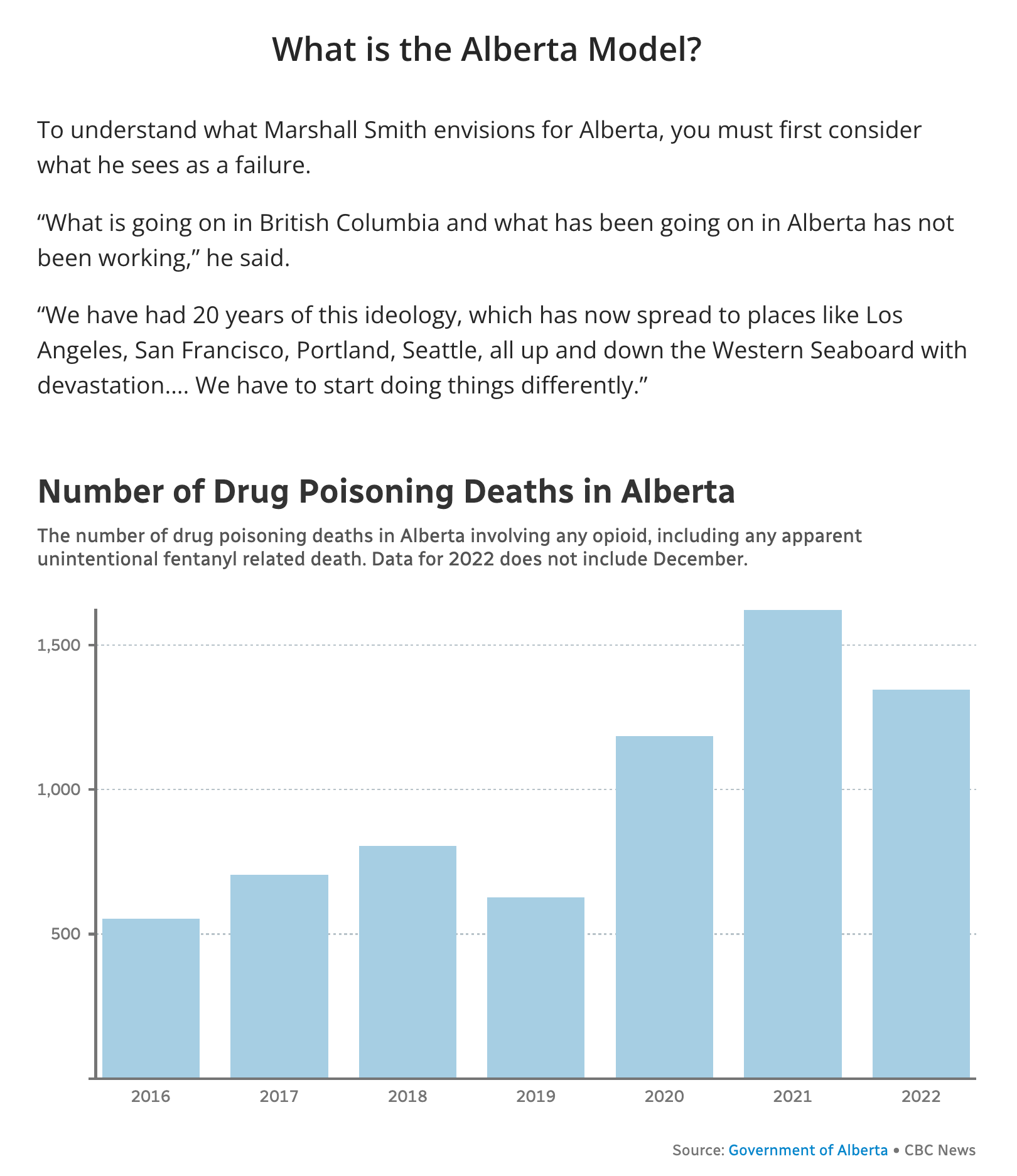

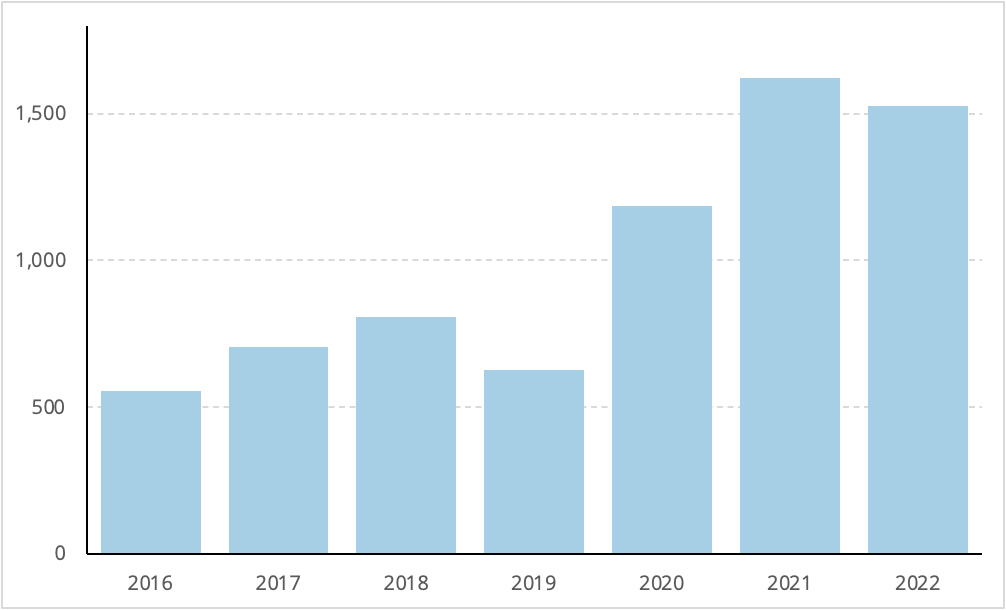

CBC heads up a section explaining the Alberta Model with the following graph, which presents a 15 or 20% decrease in opioid toxicity deaths from 2021 to 2022.

Thing is, this decrease misleads the state of the crisis in Alberta.

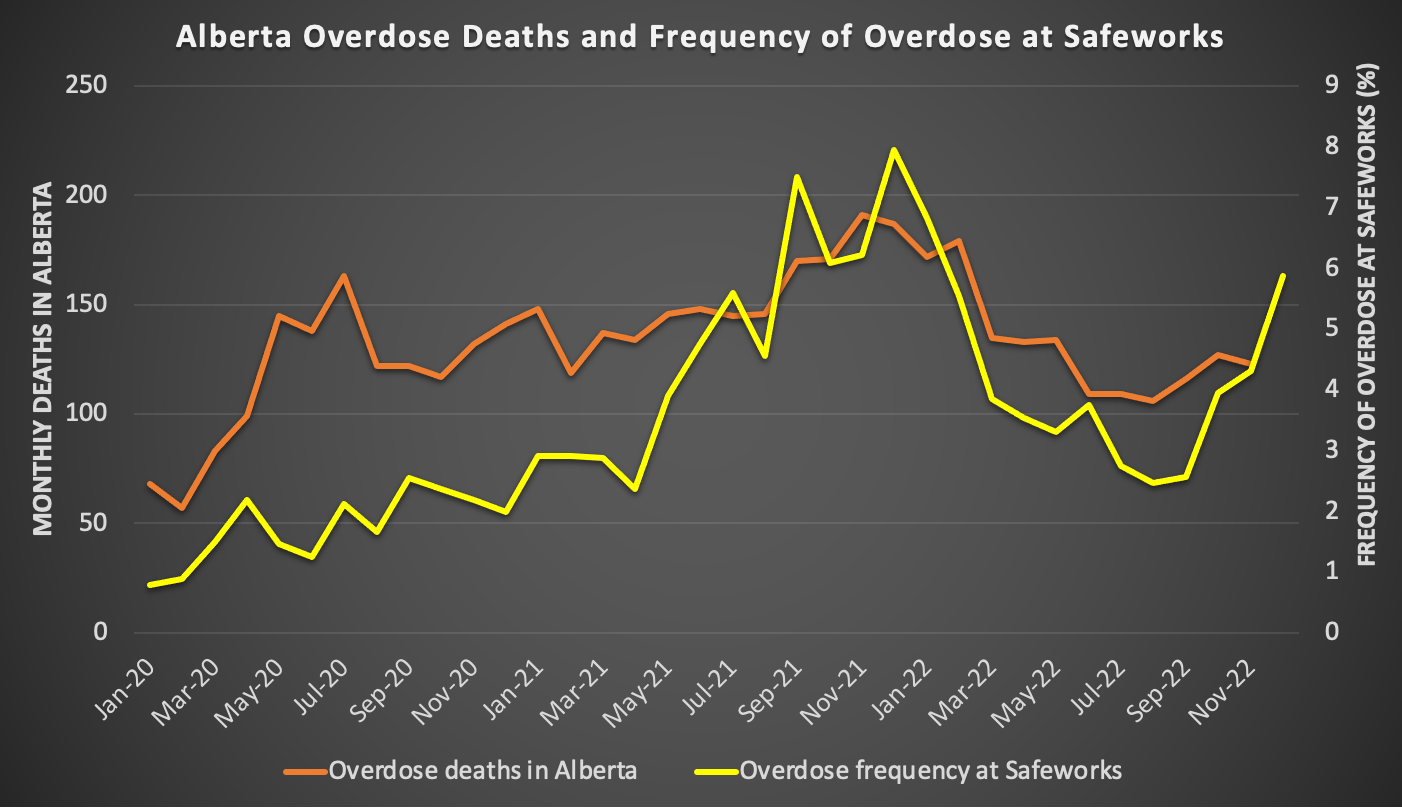

First, in tiny lettering above the graph, it mentions that the dataset doesn’t include December mortalities. Following the local overdose rate at Safeworks supervised consumption site, we can expect December mortalities to exceed 160.

Second, it doesn’t account for all the hidden bodies owing to the medical examiner’s unprecedented backlog that I wrote about last week. In 2021 for example, “Undetermined cause” was the leading cause of death in Alberta — 3,362 to be exact — owing to this backlog. We can add at least another 20 deaths on account of this, given the increase in original reporting of 1,602 to the currently reported 1,623 for 2021.

So, fixing that graph, with 160+20 additional mortalities for 2022, totals 1,526 versus 1,621 in 2021.

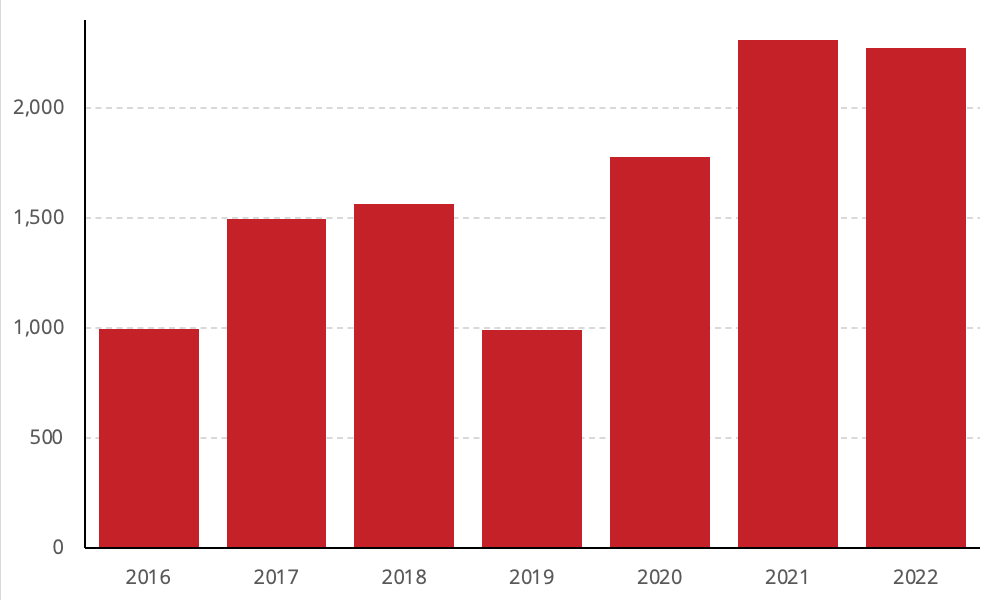

And once we have the adjusted data in front of us, we can see that the ‘Alberta Model’ isn't in fact working any better than anywhere else, including BC — near-identical trends right back to 2016, mostly owing to overlapping drug supply toxicity. Note that these BC data show all drug toxicity deaths, while the above Alberta graph only shows opioid toxicities, to match the CBC article. These are closely comparable anyway, because the vast majority of drug toxicity deaths involve opioids. Population-adjusted total drug toxicity deaths in BC have been slightly higher than Alberta every year of the crisis.

But at their root, the crisis in both provinces is a direct consequence of drug prohibition, which abolishes any opportunity for quality control. Lack of access to treatment can impede some individuals’ ability to achieve ‘recovery,’ however the individual defines it, but narrowing their options to fit within a moralistic, abstinence-only definition of recovery has deadly consequences.

The central problem: we can’t get out of this crisis without quality control in the drug supply. I was given a few minutes on Global Edmonton’s Saturday newscast to discuss this (with apologies for the horrendous stock footage they used).

Here’s what I mean. When we compare the frequency of people non-fatally overdosing at Calgary’s supervised consumption site with the number of monthly deaths across Alberta, the correlation is extremely high. And right now, the frequency of overdoses is skyrocketing, so we’re likely heading back into a mortality spike not unlike what we saw in late 2021.

Will existing efforts to expand access to certain opioid agonist therapies help? Probably. But the intervention that will immediately reduce people’s exposure to the toxic drug supply is, intuitively, reducing its toxicity by regulating it.

“A harm reduction-only approach”

CBC’s violins pick up intensity while Marshall Smith insists that until recently, Alberta’s approach was “out of balance… harm reduction-only.” This is a full dose of disinformation, given that aside from methadone and sterile needle supply, harm reduction options barely existed in Alberta until 2017.

That year, Alberta’s first supervised consumption site opened in Calgary — 14 years after Vancouver’s Insite opened and a decade after studies had shown massive improvements in public health. To this day, there remains just one site for Calgary’s 1.6 million residents — an abominable failure of government at every level.

Smith also implies that BC is holding steady to this “harm reduction-only” approach, ignoring massive new investments in treatment from the BC government, 3,200 beds already in place (versus 1,300 in Alberta) and a paradigm in which harm reduction responses occupy a sliver of relevant budget dollars.

It's beyond disingenuous for Smith to suggest a focus on harm reduction comes at a cost to abstinence-based treatment. People seeking abstinence should be supported, but they have to first survive exposure to an increasingly volatile drug supply. Given how long many people struggle before achieving abstinence, mitigation is needed. And for those not seeking abstinence, harm reduction can be seen as a more permanent strategy.

Smith then states that “our model is not abstinence-based. It’s recovery-oriented.” But how does that square with either his prior statement that “the goal of treatment is to get clients off of drugs” or the campaign waged across the province to shutter supervised consumption sites, collapse the minimal current access to regulated drugs, and villify harm reduction?

Transparency is needed

Meanwhile, we just received the devastating news that another participant in one of Alberta’s addiction treatment programs has died inside the facility.

We don’t know how many people die in these programs.

We don’t know how many die in the weeks and months after participating.

We don’t know how many exit these programs into houselessness.

We don’t know how many programs offer non-abstinence options.

We don’t know how many offer non-Christianized options, have Indigenous-led healing or train staff in trauma-informed care.

We don’t know how long the wait lists are.

We don’t even know which facilities stock naloxone.

We don’t know very much, but we are committing many hundreds of millions of dollars based on flimsy data. Here’s a complete list of the data that every government investing in these programs should be sharing with the public for evaluation.

Meanwhile, I have serious misgivings about the connections that the so-called Alberta Model has to some potentially unsavoury organizations in the treatment space. You might want to read up on the harrowing allegations around Last Door Recovery Centre. (Update: former Last Door employee Adam Haber was convicted on two counts of sexual assault on February 27, 2025.)

Want to learn more about Marshall Smith's history in Alberta and BC? Don’t miss these well-researched articles from Jeremy Appel, Ben Mussett, and Jeremy Hainsworth.