Edmonton's compassionate underbelly

Boyle Street outreach workers were prohibited from distributing supplies to unhoused people in train stations. Others are taking up the slack.

There’s a hidden gem in Edmonton you’d only discover on outreach among the city's unhoused communities.

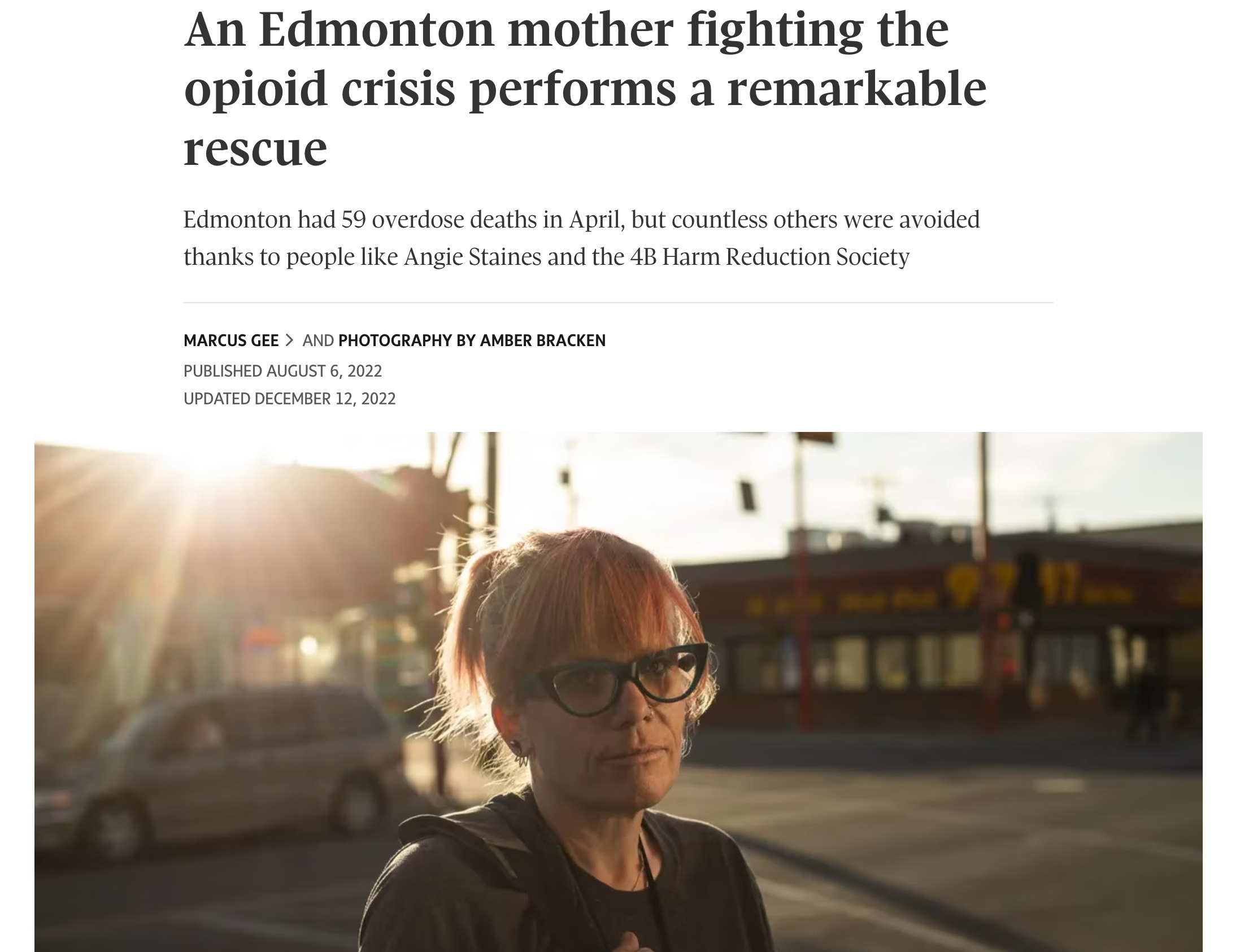

On my recent visit in mid-February, I joined Angie Staines and her team at 4B Harm Reduction for an outreach shift — a routine we’ve fallen into since we met in 2021.

Standing outside the Milner Library for introductions with the team and a couple smokes, I finally got to meet Angie’s son B. In one of the most dramatic stories told last year, Angie and her team found B overdosing one day and saved his life. (She also told about the rescue on Duncan McCue’s Helluva Story - keep tissues handy.)

A guy in a nearby stairwell was nodding hard after a heavy dose. A Hope Mission van was on the way to bring him to shelter, so a couple of us stayed behind to monitor him and wait for the van.

The person with me was Raye Cameron. Twenty-something and exuding both youthfulness and deep purpose, Raye gives the impression of knowing exactly what he wants to do and how he wants to do it.

Some wire got crossed in the van dispatch, and it took an hour to arrive as the mercury kept plummeting. We helped our buddy from the stairwell to his feet and into the van with a few smokes in hand for later, and Raye jotted down the shoe size to pick up for him the next day — his runners were reduced to scraps.

We caught up with the rest of the 4B team, who had dove into the underground train tunnels, despite the new outreach bylaws halting the distribution of supplies by outreach groups. These were ostensibly to align the outreach efforts with transit’s position that “visibly using a controlled substance on transit property is ‘inappropriate behaviour.’"

More punishment, more carceral logic.

(Strictly speaking, those new rules were specifically targeted at transit-funded groups like Boyle Street, but the criminalization of these activities tends to create a blanket ban in the eyes of the enforcement teams on the ground.)

After distributing food, safe use supplies and smokes (I snagged this job: Belle of the Ball, as AAWEAR’s Marie Ferraro would say) to a few scattered groups doing their best to avoid unwanted attention from transit cops, we met a group of seven or eight tucked into a quiet corner above some escalators.

An announcement blared: "The group consuming drugs in the alcove should be reminded this is not allowed in the station and there are officers on their way. You have five minutes to vacate the premises."

But one woman seemed uncertain. Raye approached her.

Raye had learned to sign a few years back, making him a rare and precious outreach worker able to communicate with folks who are hearing or speech-impaired.

The two went into rapid-fire discussion while the rest of us stared in awe. Raye’s face was stretching, rising, falling, contorting and beaming like a mime in a fast-motion flip-book. He told me afterward that you turn a statement into a question by raising the eyebrows: facial expressions lend meaning to the hand gestures.

The unhoused woman was clearly ecstatic — embedded in her community, but unable to express herself fully to many of those around her. Now, it came gushing out.

Raye is known among these communities in Edmonton. To hear Angie tell it, the folks who communicate by signing grow visibly excited when they see Raye approaching. This was written all over the woman’s face. She hugged him tightly before following her group toward the exit, back into the cold.

@elsthomson @RayeCameron171 @RayeCameron171 is a literal angel!!!! 💗💗

— Harm reduction saves lives (@treatysix) 2:10 AM ∙ Mar 7, 2023

To say these are ‘tough times’ for people experiencing houselessness feels glib and flippant. Life expectancy is halved. They lose friends every week. Calgary and Edmonton each allowed >240 unhoused deaths last year — roughly 1 in 10 unhoused people.

Imagine if the death rate of any working-age population hit even 1%. We have a values problem in this country.

Meanwhile, the crackdowns persist: more fences, more police, criminalization of outreach workers, deployment of an unaccountable UCP hit squad, replacement of loitering tickets with a hard ban on drug use, or administrative violence to force unhoused drug users into abstinence.

Always new framing, always the same effect.

In such times, moments of exuberance are priceless. Thanks Raye.