Clearing the Plains 2.0: Alberta Drug Policy is Indigenous Genocide

Framing drug toxicity as a tool of land occupation can guide settlers to reposition their grief from individual tragedies to collateral damage of genocidal policy.

This piece was conceptualized and written with Michelle Robinson (Mohkinstsis), Terrill Tailfeathers (Mohkinstsis) and Will Mawer-Cardinal (Amiskwaciwâskahikan). Follow Michelle at Native Calgarian, Terrill on Bluesky and Will on Instagram.

"The research tells us what [Indigenous communities] already know. It's the multi-generational impacts of historical traumas, residential schools, and sexual abuse that brought these young people to addiction and to the streets. This doesn't ‘just happen.'" -Kukpi7 (Chief) Wayne Christian, The Cedar Project

The project of Canada has always been to secure land for resource extraction.

Land occupation explains “Clearing the Plains” — starvation through buffalo eradication.

It explains the 1876 Indian Act, reserve and pass system to corral Indigenous peoples.

It explains the 1884 Indian Act to criminalize them via selective alcohol prohibition.

Land occupation explains the 1884 launch of Indian Residential Schools at High River, Alberta, and it explains why Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and the territories housed by far the highest concentrations of these ‘schools.’

It explains the 1895 Indian Act banning ceremonies across the plains and northwest coast.

It explains the Sixties Scoop and ongoing family separation that unplug Indigenous people from their cultures.

Land occupation explains why colonial governments deflect liability for failing to regulate poisoned drug markets by emphasizing “addiction” as central cause of toxic drug deaths, instead of histories and policies placing select peoples at greatest harm.

It gives rise to an alternative explanation for governmental inaction: that land occupation in an ostensibly peaceful state requires policy tools that inflict disproportionate harms on Indigenous populations. By eroding options for people at risk of drug toxicity and choosing carceral instruments including mandatory treatment, the Alberta Government stands out among provinces.

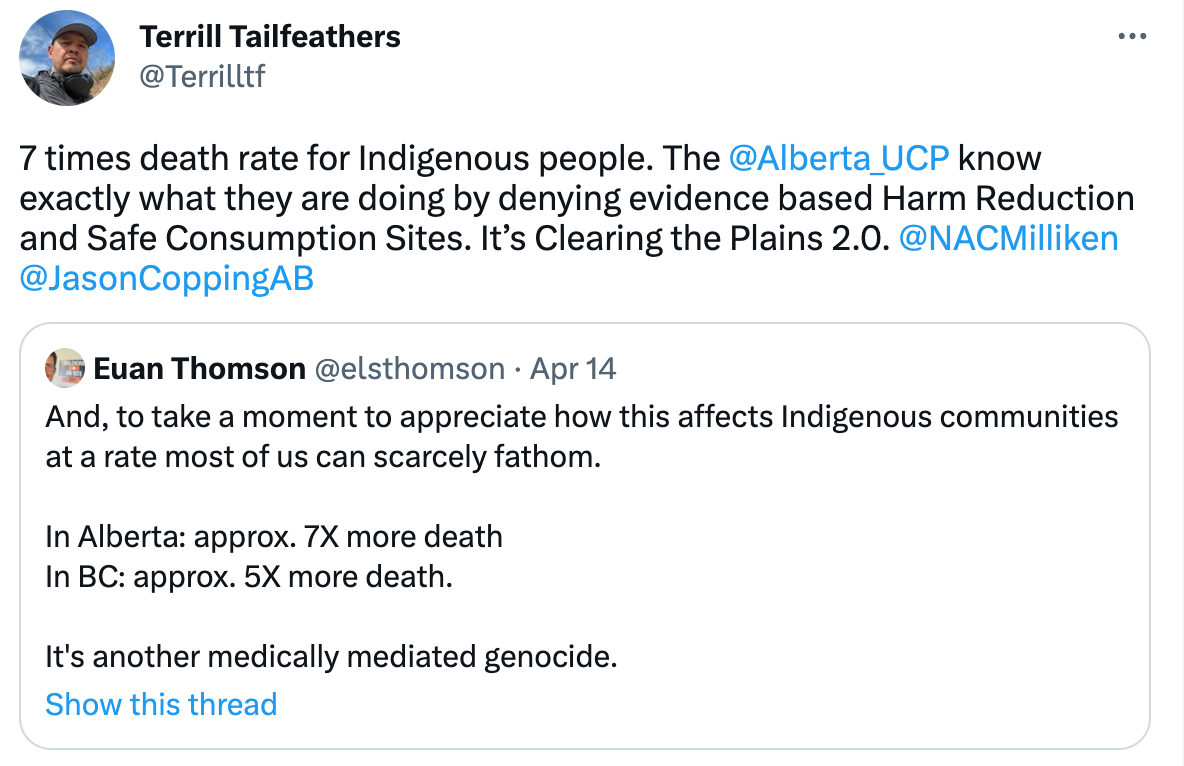

Public conversations should locate the impacts of drug prohibition on settler populations within the recognition that, by accelerating drug toxicity harms disproportionately borne by Indigenous people, drug prohibition legislates Indigenous genocide.

In adopting this lens, we must guard against ways that forces of land occupation will reinvent genocide as intensifying public outcry dismantles drug prohibition.

Strip-mining safe spaces

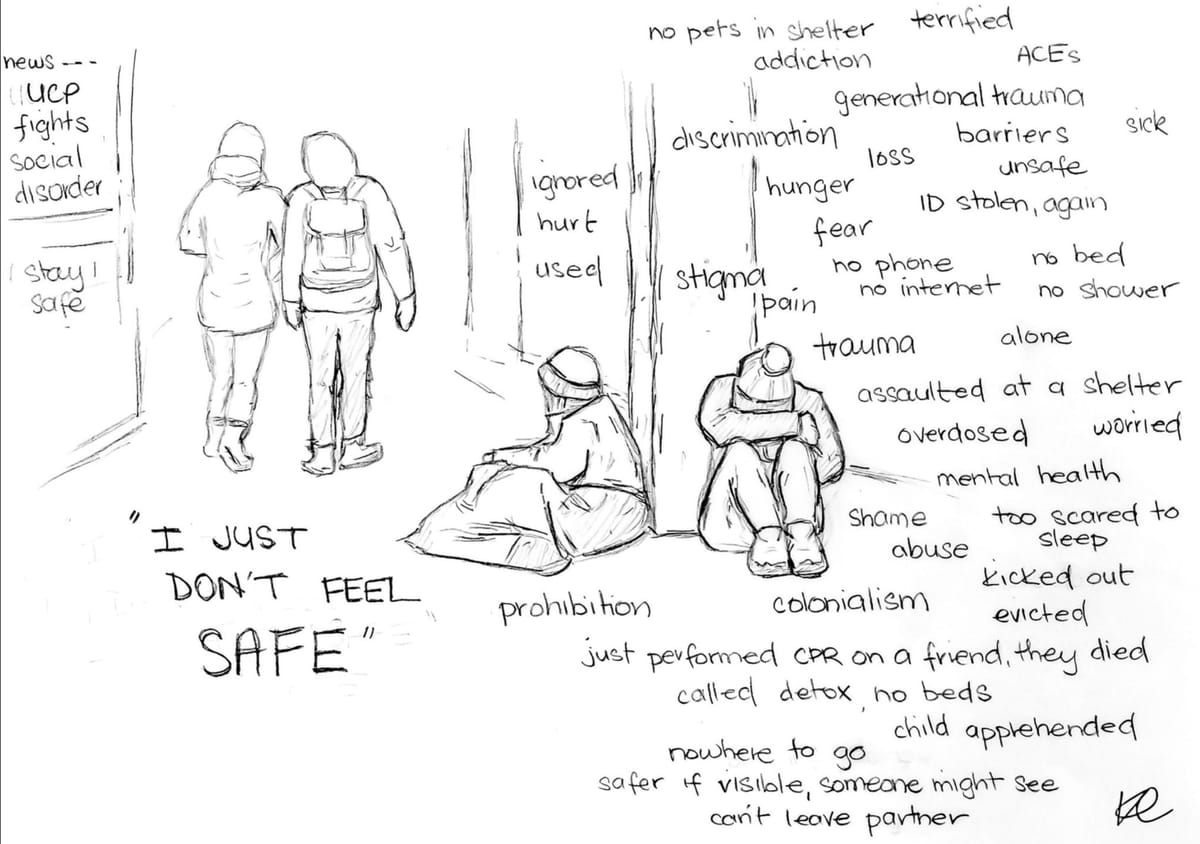

Take any media platform on any given night, and you’ll find unhoused people being cast as dangerous. But criminalizing people for being unhoused is ironic, when you realize half of unhoused people in Alberta cities are Indigenous – descended from people for whom “unhoused” is largely meaningless.

And yet, we still insist on occupying their space.

It’s in the way we spend city resources: encampment evictions, unsafe shelter spaces, hostile architecture and enforcement of loitering laws in public spaces such as train stations.

Between Calgary and Edmonton, nearly 500 people died unhoused in 2022, most frequently from drug poisoning. Many others froze to death. Tragic, easily preventable deaths. How does the erosion of options for urban Indigenous peoples reflect on our society, as we claim to work through the Truth & Reconciliation Commission findings?

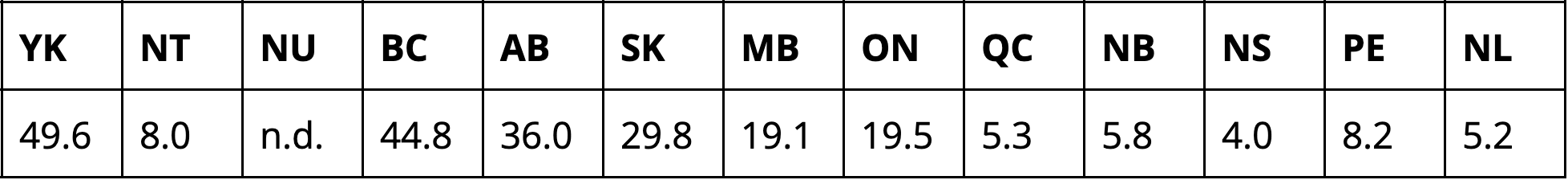

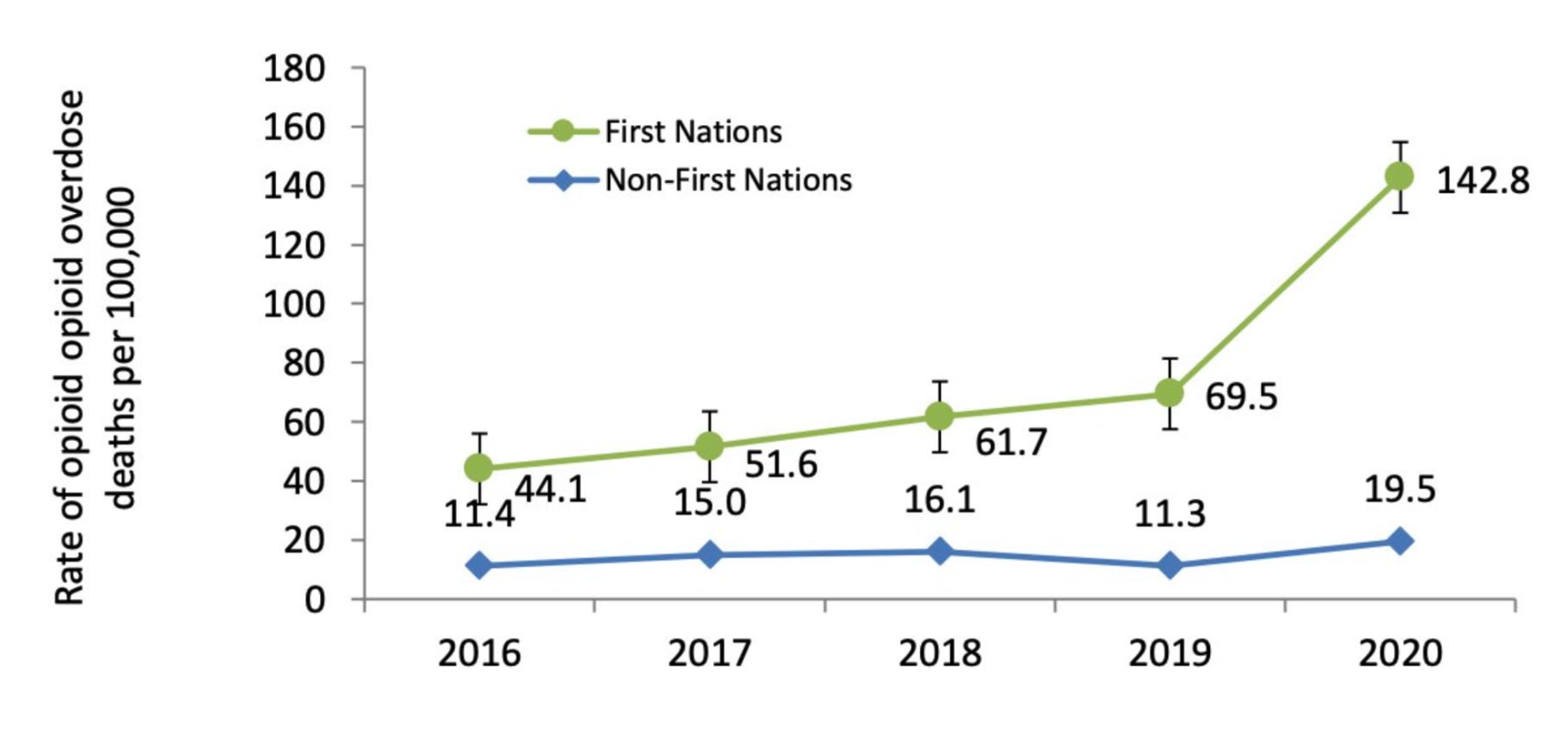

It's hard for most of us to face head-on. But what can't be ignored: in 2020, the last year for which these records were made available, First Nations people in Alberta were over seven times more likely to die of opioid poisoning than non-First Nations people. (Update July 2024: New data were recently released and revealed that First Nations people in Alberta were up to 8X more likely to die of drug poisoning than non-First Nations people in 2021 and 2022.)

This shows up in local policy, like in August 2021, after Wetaskiwin city council voted to close the town’s only shelter. Sixty people, primarily Indigenous, were driven out of town. They regrouped behind the local Walmart and set up a makeshift camp.

Two months later, four of them were dead, including one by suicide on the nearby train track and another by drug poisoning. A local told us folks in town were fed up with people building fires in their backyards to keep warm.

This pattern is replicated in towns and cities across the province. Erosion of services for urban Indigenous people while police crack down through fear mongering, bogus transit tickets and their ensuing warrant executions is an extension of the stigma that drove these deaths in Wetaskiwin.

The 2020 closure of Lethbridge ARCHES, the country’s busiest supervised consumption site, proceeded despite massive increases in drug poisoning early in the pandemic. Lethbridge now doubles the provincial death rate. Edmonton’s Boyle Street Community Services lost its SCS in 2021 and local EMS calls immediately shot through the roof. Red Deer looks to be next.

Make no mistake: the government is fully aware that SCS closures mean more deaths.

Extractive capitalism takes root in land occupation but reaches deep into the institutions created to maintain it. Today, we can observe the extraction of value from people who use drugs, as the addiction treatment industry pushes for legislation to force abstinence on people who, according to the UCP government, need “compassionate intervention.”

Will this follow Australia, which repealed its 2013 Alcohol Mandatory Treatment Act after 97% of those forced into abstinence were Indigenous?

More likely, the harms that stem from forced abstinence are baked into the plan.

Removing safe spaces to force people into unsafe ones devastates Indigenous communities. The deaths that follow are colonial violence.

Can settlers see themselves or their families in the numbers?

Family values

“The doors are closed at the residential school, but the foster homes are still existing and our children are still being taken away.” -Old Crow Chief Norma Kassi at the Northern National TRC Event in Inuvik, 2015

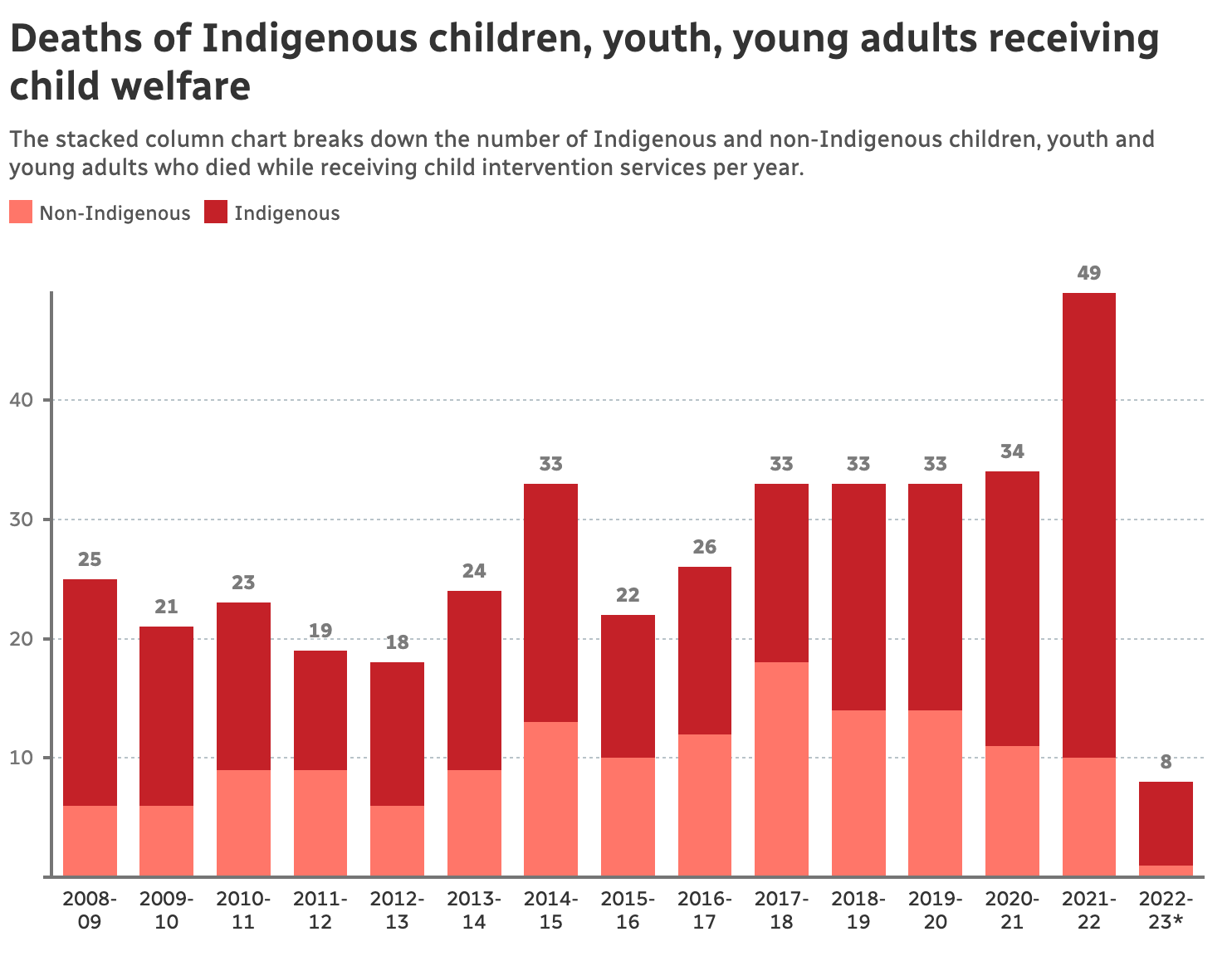

In Alberta, Indigenous children are 21 times more likely to be taken into provincial care than non-Indigenous children and make up a staggering 80% of deaths under provincial care. Forty percent of these deaths are from illegal, unregulated drug toxicity.

“Children who had been bullied and physically or sexually abused carried a burden of shame and anger for the rest of their lives. Overwhelmed by this legacy, many succumbed to despair and depression. Countless lives were lost to alcohol and drugs.” -Truth and Reconciliation Commission Final Report

The neglect doesn’t end in care settings: children “aging out” encounter increasing hurdles. In 2021, the UCP reduced the Support and Financial Assistance Agreements age cut-off, only to “restore” some funding in March. Despite opioid toxicity leading all causes of death among young people, the UCP opted against funding dedicated supports for opioid use.

Drug-related harms to family structures are woven between Indigenous children and their mothers. In BC, First Nations women are 11 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than non-First Nations women. As the Cedar Project reports, “After having a child apprehended by the state, women affected by substance use report deteriorating mental health, symptoms of PTSD and psychological distress, and increased drug and alcohol use to cope with loss and grief.”

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Women, Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA already showed us how our systems neglect atrocities against women. That this systemic neglect has metastasized into the toxic drug crisis should surprise no one. At what point do we recognize it as intentional?

Our carceral system plays a central role too: Canada just passed a morbid milestone with Indigenous women making up more than half of incarcerated women. Over 40% of incarcerated people in Alberta and over 80% in Saskatchewan and Manitoba are Indigenous. Around half of Indigenous incarcerations in Alberta are for “administration of justice” offences: charges levelled primarily through heavy policing of a population. Sure enough, this is double the rate seen among non-Indigenous prisoners.

When Pierre Poilievre, Danielle Smith, Mike Ellis and others rage about bail reform, they are not pointing out legitimate flaws that decrease public safety. They are dog-whistling for more Indigenous incarceration – more family separation, more cultural disconnection, and more downstream harms for Indigenous people.

Cultural connection is a determinant of health

Through a series of landmark studies that followed cohorts of young Indigenous people in Vancouver and Prince George, the Cedar Project is uncovering colonial underpinnings of the devastating statistics we have discussed. For example, Indigenous women who grew up with a traditional language were half as likely to attempt suicide. Conversely, participation in drug treatment programs (largely rooted in Christian values) was associated with increased suicide attempts.

Consider what urban Indigenous peoples experience at the hands of civic authorities: encampment “sweeps,” closure of services to make way for hockey arenas, crackdowns on unhoused transit riders and routine stripping of their property rights by police as they hear their nylon tents being shredded.

And yet, Indigenous cultures aren’t broken: their injuries heal through channels of community connection, resurrected identity, and reclaiming of space that are invisible to most settlers.

Will Mawer-Cardinal explains how ceremony – long throttled by the prison guards of land occupation – nurtures community healing as urban Indigenous people share their cultures through these invisible channels.

These are acts of resistance against a genocidal system: if culture is protective, then ceremony is survival.