Calgary police "image recognition" by Hootsuite identifies individuals in photos & videos posted online

Documents show that two years after being caught using Clearview AI facial recognition software, Calgary police signed contracts for AI software that scours photos and videos for individuals. Have police agencies across Canada taken a secret shortcut to facial recognition?

“At the moment, the Calgary Police Service has no intention of going near any facial recognition software that would utilize images we have no control over or we can’t verify,” a Calgary police spokesperson told the Calgary Herald in 2020. Two weeks earlier, its officers had been caught "testing" Clearview AI facial recognition software to scrape personally identifying images from social media posts.

While this about-face may have saved face under public scrutiny, new documents obtained by Drug Data Decoded suggest Calgary Police Service (CPS) quietly pursued its original intent. The documents reveal that its current social media surveillance capabilities include AI-based "image recognition" that identifies individuals in photos and videos.

In other words, CPS is paying for facial recognition technology.

The contracts, covering 2016 to 2024, show that CPS spent from $14,000 to over $100,000 annually on social media monitoring software. CPS maintained up to one hundred user accounts with four different companies: Hootsuite, Salesforce, Meltwater and Talkwalker (acquired by Hootsuite in 2024). Up to nineteen user accounts were for non-investigative activities, likely reflecting those held by media relations staff.

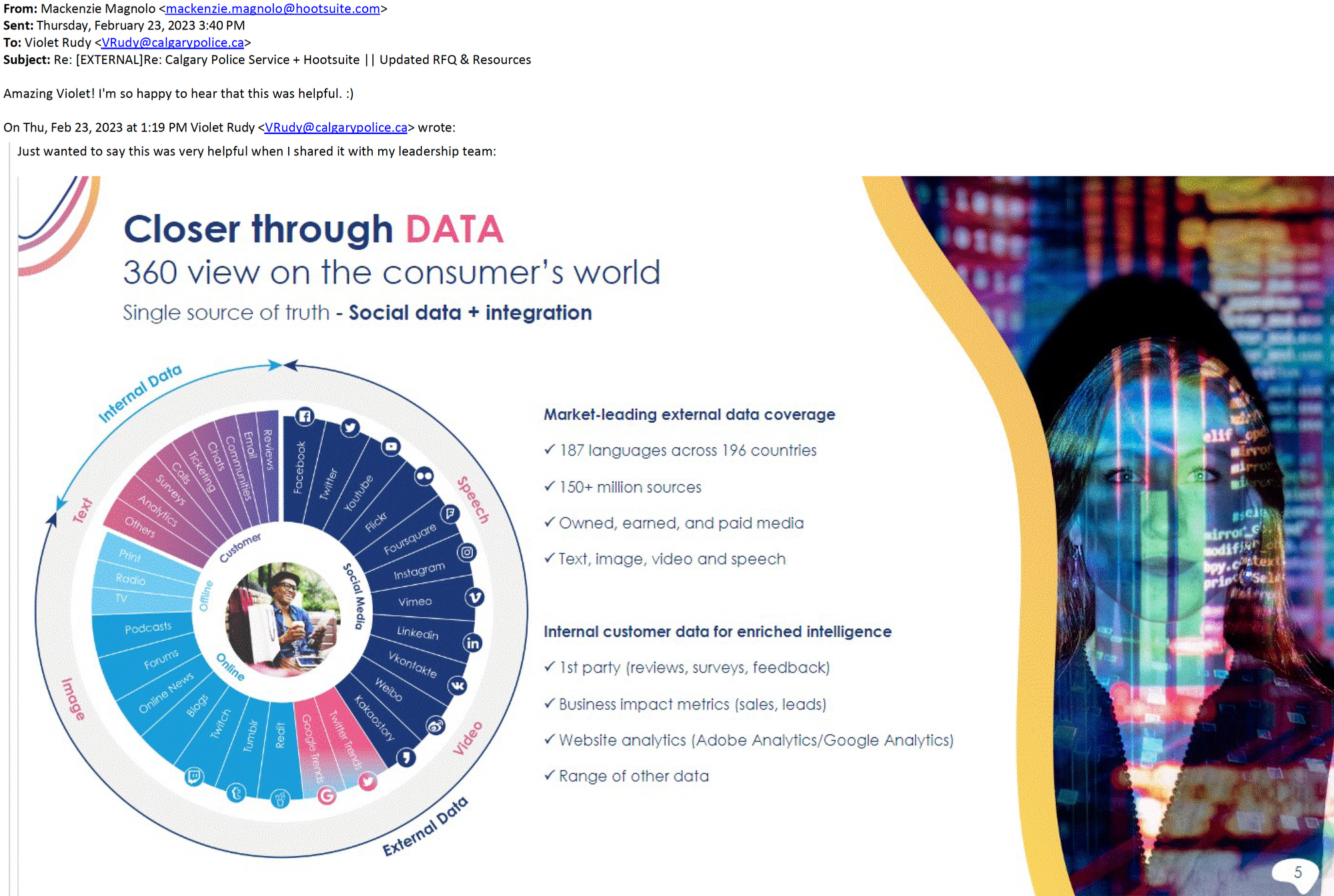

Two of the companies contracted since 2022, Meltwater and Talkwalker, use AI-based image recognition. Both companies explain that this technology can identify people within photos in their online materials. Meltwater defines image recognition as "a type of artificial intelligence (AI) that refers to a software‘s ability to recognize places, objects, people, actions, animals, or text from an image or video.” Meanwhile, Talkwalker boasts of its software's ability to identify a celebrity or influencer from an image, a clear example of facial recognition.

Hot stove, revisited

So, despite its previous declarations, CPS appears to have adopted facial recognition for social media surveillance by enlisting with Clearview AI competitors.

In the 1,566 pages of documents (many duplicated), CPS repeatedly refers to “open-source information,” reflecting how its internal policy categorizes social media posts. CPS conducts the surveillance to harvest and store posts that include specified words, tags or names of individuals, as well as to monitor press reports.

Given the image recognition software in place since 2022, CPS also has the ability to detect and catalogue people and places from photos and videos posted to social media. The analysis of video by Talkwalker appears to have been a major selling point for CPS, as its media relations procurement lead told the vendor that their “leadership” would find these capabilities most compelling.

It is unclear if this referred to the executive leadership team including the chief and deputies (who are not named in the documents) or the director of the media relations unit, which operates from the Office of the Chief.

"There is currently no control over police in Canada. They are out of control."

-Dr. Kevin Walby, University of Winnipeg

Dr. Kevin Walby, Professor of Criminal Justice and Director of the Centre for Access to Information and Justice (CAIJ) at the University of Winnipeg, told Drug Data Decoded that the activity carried out by CPS "is dragnet surveillance, this is mass surveillance, and this is not supposed to happen in a liberal democracy with a Charter of Rights and Freedoms. There is no reasonable probable grounds for this."

CPS is not alone in pursuing this "dragnet" surveillance. Meltwater's sales pitch to CPS named existing clients that included the municipal police services in Edmonton, Waterloo, Hamilton, Saskatoon and York, the provincial police forces in Ontario and Quebec, both the Ontario and Toronto police unions, and every ministry of the Ontario government.

Hootsuite is based in Vancouver, while Meltwater and Salesforce are based in the United States. Under the CLOUD Act, American tech companies can be compelled to provide the American government access to their databases, regardless of server locations.

Therefore, through these surveillance activities, police agencies and government bodies may be compromising the data sovereignty of countless people in Canada.

Even without image or facial recognition, gathering of personal information from social media by public bodies was illegal in Alberta while these contracts were signed. A 2021 Joint Report of Canada, Alberta, BC, and Quebec privacy commissions established that people's social media posts cannot be treated as "publicly available" for use by public bodies, including police.

However, a May 8 Alberta Court of King's Bench ruling concerning Clearview AI allowed that the definition of "publicly available" was too narrow in the current landscape of the internet and violated freedom of expression, which Clearview AI claimed to be exercising through its commercial activities. That ruling, however, ordered Clearview AI to destroy millions of photos of Alberta citizens. Clearview AI insisted this was impossible, as it would require manually sorting through billions of photos, a defence that Justice Colin Feasby rejected.

Michael Nunn, CPS media relations director, was asked on July 31 whether CPS is conducting facial recognition on social media posts, where these data are held by the contracted tech firms, whether the data are passed along to any other entities, and if CPS intends to cease its unlawful social media surveillance. Nunn did not respond.

Previous reporting by Drug Data Decoded showed how CPS and its sworn officers’ union use Hootsuite to monitor citizens‘ social media, but the potential for facial recognition, the contract amounts and their timelines, and the adoption of these tools by police forces across Canada were unknown at the time.

These latest documents were obtained fifteen months after the initial request for information was "lost" by Calgary police. A formal complaint eventually prompted Alberta's Information and Privacy Commissioner to issue Order F2025-14 on April 11, 2025, forcing the release of the documents. CPS demanded payment of $1,133 to release them, then violated the commissioner’s order by delaying their release another two weeks. During that contravening period, the G7 Summit came and went – under surveillance by Calgary police.

Seventeen days after the commissioner's order, Calgary police chief Mark Neufeld resigned. Two of his deputies, Raj Gill and Chad Tawfik, followed him days later. All of these resignations remain unexplained to the public.

"This is dragnet surveillance, this is mass surveillance, and this is not supposed to happen in a liberal democracy with a Charter of Rights and Freedoms. There is no reasonable probable grounds for this."

-Dr. Kevin Walby, University of Winnipeg

The CPS policy intended to guide these practices, titled Internet Investigations and Criminal Intelligence, is from approximately 2018 – after CPS began conducting social media surveillance. The policy is not publicly posted and is possibly unknown to Calgary Police Commission, which ostensibly oversees CPS policy. The commission declined to respond to questioning about it from Drug Data Decoded in May.

In the policy, CPS asserts its legal authority to "conduct online investigations." It bases this on the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, which “permits the collection of personal information from a source other than directly from the individual the information pertains to for the purpose of law enforcement." However, a considerable portion of the data-gathering activity does not constitute "law enforcement," and neither the former nor the current privacy laws in Alberta provide for police to collect or share data outside of a law enforcement context.

As Walby points out, any sharing of these data to third parties would constitute another privacy law violation by the police. He wonders if the data collected by Calgary police and other agencies in these software platforms are being sold to data brokers. The Electronic Frontier Foundation describes data brokers as individuals or companies that "sell sensitive data gathered from people’s phones to a wide range of clientele," including law enforcement.

CPS media relations director Michael Nunn was asked if people's data are being tracked after being shared to these software platforms. He did not respond.

Please consider sending this post to friends or sharing on social media

The state of Montana was recently the first in the United States to close the "data broker loophole." In other jurisdictions, this continues to allow police to buy a user's location or other personal data – without a warrant.

It is unknown if Calgary police use this back door to access personal data for warrants or other reasons.

Outside of a law enforcement context, police are using these systems to keep up with news reports. To this end, Meltwater claims to be unique among its competitors in offering exclusive alerts from Postmedia and Glacier Media through its subsidiary, Meltwater News. This is a telling integration between a tech company selling services to police and media conglomerates whose reporting tends to favour police.

While this integration was central to a proposed $210,000 sole-source contract between Meltwater and CPS from 2023 to 2026, the City of Calgary rejected the proposal and forced CPS to open the competition to other companies. In the end, Meltwater lost the competition to the Hootsuite-Talkwalker partnership. Hootsuite began onboarding CPS in March 2023.

"They chicken out each and every time"

Walby suggests these findings reflect a pattern of privacy invasion with only one solution: "The database and program should be shut down. The police service should be audited and investigated by outside agencies from top to bottom."

"There is currently no control over police in Canada. They are out of control."

Following this problem to its oversight bodies, Walby directs criticism at privacy commissioners' repeated failure to take a hard stance against mass surveillance. Instead of banning camera surveillance, license plate readers, facial recognition, data brokers and social media monitoring, the commissioners routinely "chicken out and cede power to police and corporations."

While scores of privacy experts criticize federal Bill C-2 as an unconstitutional expansion of surveillance powers, cascading personal privacy violations by police may already be flying under the radar under the guise of "image recognition" by surveillance tech companies.

And as people across the country awaken to their collective complicity in the Palestinian genocide, they may come to recognize these technologies as central scaffolds of Israeli apartheid and accelerants of its genocide.

Readers are encouraged to submit a freedom of information request to Calgary Police Service concerning their personal information by filling in the form below and sending it to access@calgarypolice.ca. To adapt this request for other police or government agencies, the language on "records" in this request can be slightly modified to match the sections and subsections of your local freedom of information law:

Read the 1,566 pages of documents released under OIPC Order F2025-14:

If you have additional information on this story, please get in touch at info@drugdatadecoded.ca, where media can also request documents related to this story.

An early version of this story was shared with paid subscribers on August 5.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.

This content is not available for AI training. All rights reserved.