BC government faces legal challenge as national news media promote forced abstinence

Two long-form articles in national news outlets are promoting the BC government's "secure care" policy the same week that the government faces a pivotal legal challenge on its expansive interpretation of the Mental Health Act.

On May 29, the BC government led by Premier David Eby will face a federal legal challenge concerning the province’s longstanding use of its Mental Health Act to detain people under involuntary treatment. The Act has recently been interpreted by Eby's government as an open door to mass medical incarceration of people who use drugs, and the government has begun opening hundreds of new spaces to accommodate it.

The legal challenge was originally advanced by the Council of Canadians with Disabilities in 2016. In 2022, a Supreme Court of Canada judge ruled that the case could proceed despite an argument by the BC government that the organization should not have the right to bring the case. On May 27, 2025, BC-based Health Justice announced it was granted intervenor status. The case will proceed as a challenge under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The weekend before the court proceedings are set to begin, Globe and Mail readers in BC awoke to a bleak front-page headline: "How fentanyl transformed Victoria’s Pandora Avenue from downtown hub to open-air drug market."

The story and a Maclean's piece that followed on May 26 are the latest examples of the way newsrooms are manufacturing consent for provincial expansions of forced abstinence. This follows a pattern that Zoë Dodd and this author documented for The Breach in February.

The Globe article invokes the trope of downtown apocalypse through standard visuals of "people on the sidewalk... semi-conscious and bent over" while "blankets, cardboard and trash clutter the pavement." It then proceeds to interview and quote six business owners, four police officers and a homeowner, among others variously embedded in the city's power structures.

The sum total is a call to arms against the unhoused population in Victoria, many of whom are portrayed as beyond help.

Though the article claims to have surveyed thirty unhoused residents of Pandora Avenue on how many overdoses each had experienced, none was quoted or allowed to respond to the accusations levied by police, business and home owners that they were ruining the city's streets, businesses and homes.

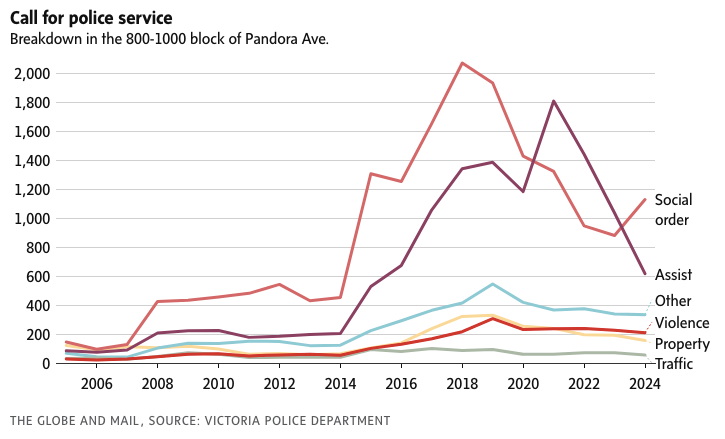

One police officer is quoted describing his inability to solve the disorder as "shoveling water with a rake,” suggesting the need for new enforcement tools. The word "crisis" clocks its seventh count in the article shortly before the police data describing the situation are provided. The data show that all calls to police along Pandora Ave have seen steep declines since 2019, and property crime has fallen to near-2010 levels. Violent incidents, still above their baseline, have also declined roughly 30% since their 2019 peak.

So despite the repeated claims that the problem is intensifying, police data suggest that crime and disorder on Pandora Avenue have been steadily resolving for five years.

The article then cites a Leger poll showing that "73 per cent of Victorians think downtown has gotten worse in the last year, far higher than any other Canadian city." Most respondents blamed homelessness and drug addiction for the decline.

These perceptions, linked throughout the article to crime, also do not align with the trend shown in the calls for police service.

In February, Leger's VP for Western Canada told a Victoria radio station that "even though the state of deterioration perceptions are higher, the number who have experienced any one of those [crimes] is actually about on par with the rest of the cities.”

Pivoting to the solution

As the story builds sympathy for frightened Victorians and failing businesses through selective framing, an ominous spectre takes shape in the background: that the solution is the BC government's new measures to institutionalize potentially thousands of people each year under long-term forced abstinence from drugs, or "secure care" in the government's preferred language.

Julian Daly, executive director of Our Place Society, is quoted as making "no apology for saying" he supports the BC government's manoeuvring, as it rushes to open hundreds of new ’secure care’ beds.

Notably, the board of directors for Our Place oversees the executive director and includes a lawyer in the BC Ministry of the Attorney General, a senior bureaucrat in the BC Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, a 28-year Victoria police veteran and a VP at the corporation that operates BC's "first point of contact for 9-1-1 callers." The BC government is currently undertaking an independent review of that company after concerns were raised about its "lack of operational and financial transparency and performance, and escalating costs."

Next in the Globe article, Victoria city councillor Dave Thompson, who describes himself as a pragmatic progressive, is quoted saying the city's biggest problem is the dysfunction created by social disorder.

After publication, Thompson replied to the Globe's Bluesky post of the story, stating "what is needed for Pandora [Avenue] is more mental health supports, more detox-treatment-recovery supports, and for the few who need it more secure care.” (Emphasis added.) He highlighted that these are provincial responsibilities. His spouse, Diana Gibson, is a sitting member of the BC cabinet.

In the online exchanges that followed, Thompson held firmly that that there is a meaningful distinction between secure care and forced abstinence, which he says he does not support. According to Thompson, "secure care can [also] include harm reduction and medication- assisted-treatment approaches."

Vancouver Island-based Doctors for Safer Drug Policy dispelled this notion in a reply to Thompson, describing secure care as "the government’s preferred euphemism for forced abstinence." The doctors also contested Thompson's assertion that doctors broadly support the government's approach. Thompson agreed to consult with the physician group following the exchange.

A separate group has created an open letter where BC health care workers can express dissent to forced abstinence of patients and clients. The letter currently has nearly 150 signatures.

Another Victoria city councillor, Susan Kim, was presented in the Globe story as holding an outdated, harm-reduction oriented position that has seen its "public support... collapse," a claim made without evidence in the article.

Although Kim's position is juxtaposed against the article's constructed image of "lawless and violent" encampments, Kim was not interviewed for the story.

Omitting key facts

While crime statistics do not bear out many Victorians' perceptions of lawlessness, the Globe article fails to discuss the most important factor driving houselessness in every Canadian city: housing cost.

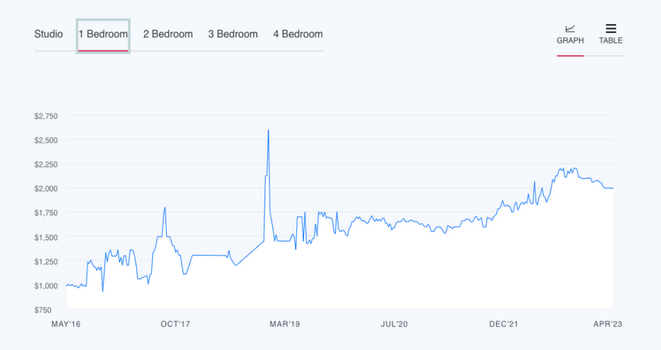

Graduate students at the University of Victoria compiled rent patterns from public data sets. Between 2016 and 2023, monthly rent on a one-bedroom apartment in the city doubled.

These data are useful context concerning the failure of businesses in Victoria's downtown core and elsewhere in the city. As one downtown business owner explained in agreement with local workers, lack of housing affordability is a big problem for business sustainability.

And while the executive director for Pacifica Housing corporation was quoted in the Globe story stating “everyone was offered shelter. Not everybody took us up on it," the story again failed to interview unhoused residents on Pandora concerning reasons for not accepting the housing that was offered, whether they recalled such an offer being made, and, if they had failed attempts in that system, what they believed were the reasons for the failure. The article takes for granted that some people are "unhouseable," in the phrasing of one police officer.

The Pacifica housing website describes its Nanaimo facility as its "lowest-barrier" site, suggesting that the barriers for housing are higher at the Victoria site. It is unclear what these barriers are, as no residents were asked.

Timing is everything

After leveraging the Lapu Lapu massacre to advance public support for institutionalization of people suffering mental illness, the BC government appears to be shoring up its legal defence of forced abstinence.

And shortly after disorder on Pandora Avenue splattered the front page of the Globe, a parallel story was disseminated in another national news outlet.

On May 26, Maclean's published a long-form piece titled "The Fight Over Forced Rehab" that lays out extensive arguments in favour of BC's moves toward forced abstinence while simultaneously rehabilitating the image of Marshall Smith. Smith has long manoeuvred to advance forced abstinence policy in Alberta but resigned his post as chief of staff to the Alberta premier in October 2024. His resignation was three months before the Globe published on his alleged involvement in procuring lucrative government contracts at inflated prices for a private health care investor.

Unlike the Globe piece, the Maclean's story briefly notes the Charter challenge against involuntary treatment but fails to explain that the challenge begins the same week the Globe and Maclean's pieces were published. The Maclean's piece limits the perspective of the legislation's opponents to just 2 of 36 paragraphs – the same space it gives to instilling fear around harm reduction services and people "smoking crystal meth right out in the open."

Maclean's also interviewed Guy Felicella, who consistently opposes forced abstinence. While the story discusses his voluntary path to abstinence, it avoided quoting him on his position concerning involuntary treatment.

In an interesting twist, a version of the story was available on Apple News the week before it was published on the Maclean's home site. During that previous week, the Globe's Alberta team published a new story revealing that Marshall Smith lived in a house owned by the sister of the private health care investor embroiled in the alleged procurement misdeeds.

But when the Maclean's story was finally published on its home site, the story was updated with the following paragraph added, according to a side-by-side analysis conducted by Drug Data Decoded:

The [Alberta government's forced abstinence] plan is proceeding without the involvement of Marshall Smith, who left his government role last October. (This February, the former head of Alberta Health Services alleged that he and others in government inappropriately interfered in procurement processes. Smith has denied the allegations, which are unproven, and has sued for defamation.)

Drug Data Decoded asked Maclean's editors why the version of the story published early on Apple News was delayed on the home site. The editors did not reply.

News media have long played a role in manufacturing consent for government policy. In his new book Copaganda: How police and the media manipulate our news, Alec Karakatsanis lays out three foundational roles of police propaganda: first, to narrow the public's understanding of public safety to that which is easily captured in police-controlled statistics; second, to manufacture fear using high volumes of selective stories; and third, to promote punishment as the solution.

The Globe and Maclean's pieces meet this definition of copaganda at a moment when the BC and Alberta governments need them most.

If you have additional information on this story, please get in touch at info@drugdatadecoded.ca.

This story was shared with Paid subscribers on the morning of May 28 and made public later the same day.

Call for support: Know professionals or academics who might be interested in supporting this work? They may be eligible to claim subscription costs for professional development – please encourage them to chip in.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.