Alcohol is toxic but so is public health right now

Thoughts about the new CCSA alcohol guidelines, after a decade working in alcohol and building a harm reduction approach in my own life.

If you follow me on the bird site, you probably know what I’m about.

But just in case: I run a business that works with small, locally-focused beverage producers, and I run a business coalition seeking to end the drug poisoning crisis through legal regulation of the illegal drug supply. I have a history volunteering in restorative justice but swam upstream a bit to attack the racist, classist war on drugs at its root. I see much of this work as honouring my partnership in Treaty 7. I try my best to see the whole field of battle.

First, let's acknowledge the elephants.

The first elephant is that we're watching public health lie to us in real time about the dangers and appropriate mitigations of a virus that remains our biggest threat to long-term health.

This failure of public health policy is closely tied to the interests of capital, and I'd recommend Spin Doctors by Nora Loreto for further reading.

Second, and more immediate to alcohol, we're also seeing public health policy fail working-age people in the unregulated drug poisoning crisis. Supply regulation is needed to save lives, but instead we get moralizing, fear, stigma: carceral thinking. In Alberta, illegal drug poisoning is the leading cause of reduced life expectancy. Where’s the public policy to regulate the supply?

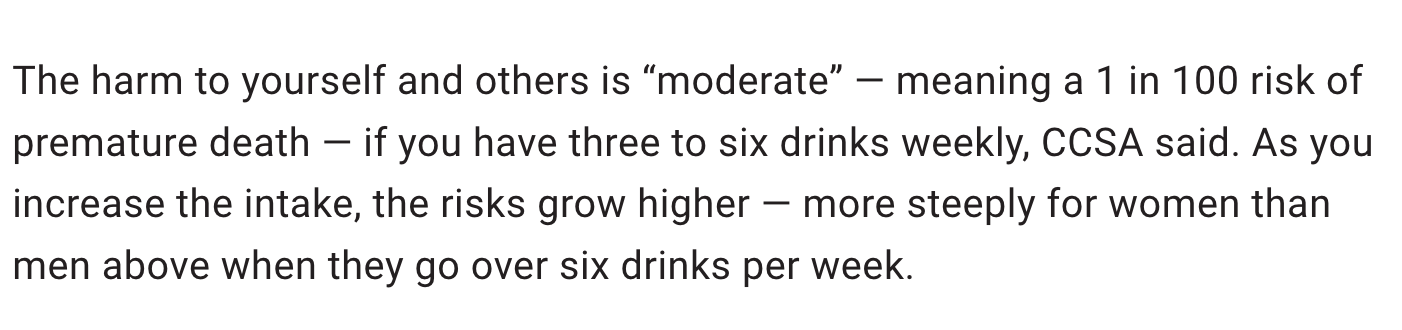

The third elephant is that alcohol IS inherently dangerous. It DOES cause cancer. It DOES cause accidents. It should be more tightly regulated, and Big Alcohol IS a real thing: international monopolies with real political power. Further reading on this (I haven't read it yet but will soon): Drinking Up the Revolution by James Wilt.

The fourth elephant is that many people need drugs, including alcohol, largely because our economy relies on exploitation and indifference that causes widespread suffering for the benefit of the few. Drugs ease suffering. Stigmatizing their use places those who need them at greater risk by reducing their access to health services and causing them to be cast aside when they do seek them out.

But this conversation must reconcile:

1. Public health is being visibly squashed under the foot of capital.

2. Greater regulation of alcohol should be paired with legal regulation of illegal drugs.

3. Alcohol's societal and political harms should be accurately identified and mitigated.

4. Most people will still want or still need alcohol - stigma can’t enter the equation.

The answer is harm reduction.

A non-moralistic, non-carceral, trauma-informed response that addresses structural reasons driving people to unsafe consumption and provides informed consent of consumption is the way forward. Informed consent means an accurate reading of evidence and the centring of people’s right to make their own choices.

What does this mean practically?

Different things for different people, but policy that only serves the privileged would ignore how systems of oppression drive people to use drugs. Consider the Sixties Scoop: Did you know more Indigenous families are currently separated than at its height?

Did you know Indigenous men make up over 30% of the imprisoned population, and Indigenous women over 50%, despite Indigenous folks making up only 5% of the total population? That Indigenous people in Alberta are 7X more likely to die of drug poisoning than non-Indigenous?

Statistics like these should be on the tip of everyone’s tongue because they clearly illustrate racialized systems of oppression that reinforce precarity. Measures to destroy these systems must accompany any calls for reduction of drug consumption. Otherwise, these calls simply reinforce privilege for those in a position to back off consumption and reinforce stigma for those who aren’t.

The point is not that any group of people inherently needs any drug (though some individuals absolutely do). The point is if we’re not willing to address the reasons they use them, we’re papering over real problems with disingenuous policy - a hallmark of neoliberal thinking.

What about more privileged folks?

Anyone willing and able to reduce consumption should be supported. How? Rein in advertising, incentivize lower-alcohol products, and require warning labels, for example. I love seeing craft breweries put out products with reduced alcohol. I still want the effect but I’d prefer more options than “standard strength” (how did we land on 5% anyway?). A good basic rule is that we don’t push drugs on people, but regulated versions should be available for anyone who wants them.

To keep your money off Wall Street and circulating closer to home, drink less but drink local. And that means identifying and avoiding multinational corporations dressed up as local producers

My worst instinct.

Morbidity and mortality from unmitigated spread of COVID will likely far outstrip harms of alcohol, and yet capital-friendly public policy places us directly in its path.

Which begs the question that if public health policy visibly isn’t working in the public interest on COVID (or regulation of illegal drugs), could public health policy on alcohol also cause us harm?

Among the scariest current trends in health is privatization of care. Care can be contingent on medical history — including substance use. Think liver transplants. Under a private model, insurance coverage and access could be significantly reduced by a history of alcohol consumption in excess of recommendations.

That should awaken people into protecting public medicine as our party bus exits onto the toll road.