Alberta virtual prescribing is carceral care: Part 2

Conflicts of interest, prison guards and police stand between health care providers and their patients in Alberta's Virtual Opioid Dependency Program.

We often talk about lacking evaluation data for heavily-funded measures like residential addiction care. So I was excited to find, while preparing this piece, a 2022 evaluation study on the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program (VODP) in Alberta.

It didn’t quite live up to my hopes.

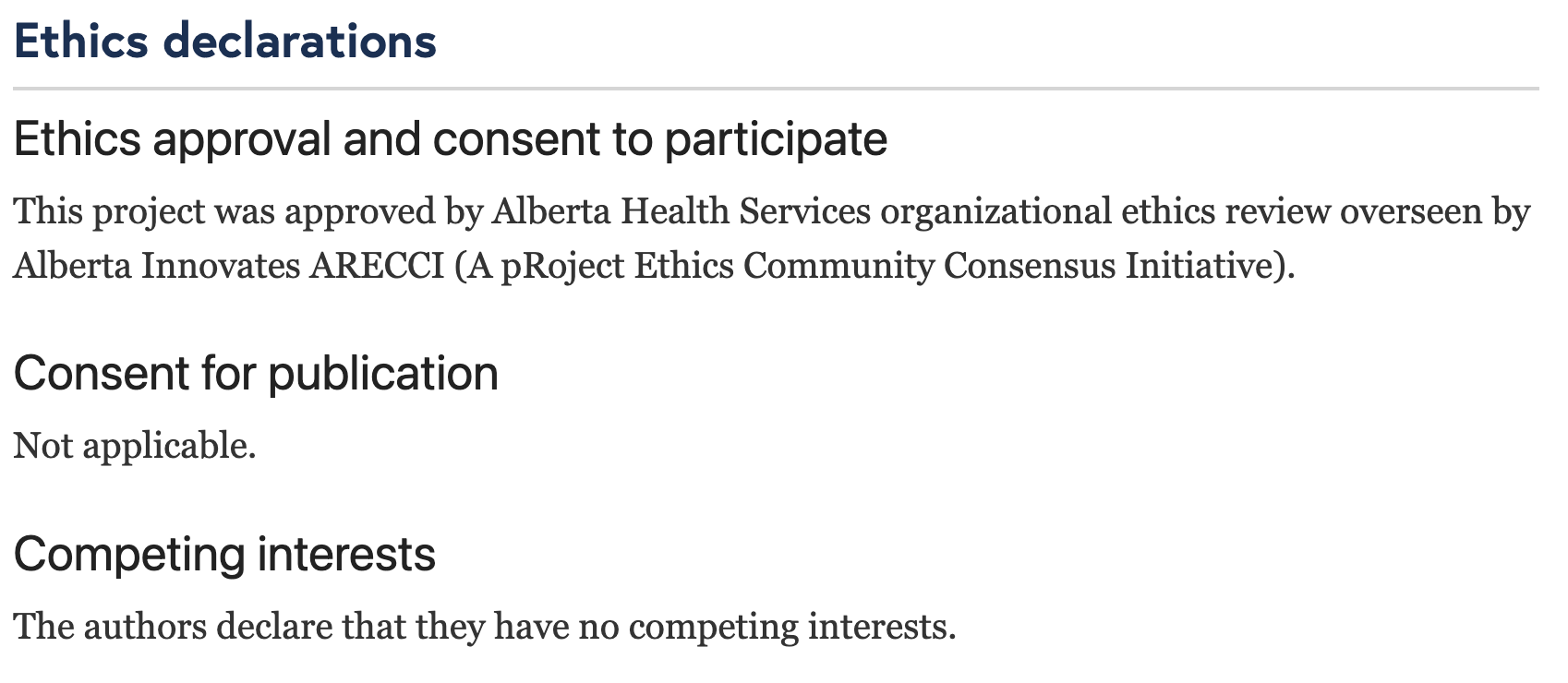

Co-authored by Dr. Nathaniel Day, Maureen Wass and Kelly Smith and published in the journal Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, the study authors declare “no competing interests.”

No competing interests, despite Dr. Day’s position as medical lead of the program under evaluation — presumably his main source of income.

No competing interests, despite Dr. Day’s repeated participation in the politicization of Alberta’s virtual care model.

No competing interests, despite Alberta Health Services cited as the only affiliate institution for the evaluation authors, and therefore the study’s sole funding source.

Failing to ensure the program’s evaluation is carried out with minimal bias is serious business, because VODP’s self-evaluation data are frequently trumpeted during politically motivated announcements by the Alberta Government.

Anyways.

In Part 1, we examined how prohibitionist logic may dictate the degree to which different opioid medications are dispensed in Alberta, including Suboxone, Sublocade, methadone and hydromorphone.

It was pointed out that of these, only Suboxone and Sublocade dispensing rates are increasing in Alberta. Both are sold by Indivior, which has heavily lobbied the Alberta Government since 2020 — the same year it landed in hot water with the American Department of Justice over illegal marketing.

We also discussed how the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program (VODP), promised on paper to extend prescribing reach into rural settings, is seemingly being co-opted by the UCP as part of their push to coerce people in detention into addiction “treatment,” a misnomer when we consider the harms introduced by forced abstinence.

Here, we’ll take a frontline care provider’s perspective. How does the UCP’s carceral worldview interfere in relationships between providers and patients at high risk?

Virtual service in a physical void

For obvious reasons, virtual models of healthcare have gained acceptance through the pandemic. In Alberta, VODP dominates the Addiction Medicine virtual care landscape. As government money (and accolades for its directors) piles up, VODP has been increasingly introduced into institutional settings, like remand and prisons.

The expansion of VODP certainly improves access for a niche group of patients, but it can’t replace the wraparound care many patients require, nor should it relieve the government of its responsibility to provide accessible care to the most vulnerable.

For example, VODP requires a phone or internet connection — not something many people who are unhoused can consistently access. If VODP isn’t relevant to the patient populations at highest risk of drug poisoning, the UCP Government advertising it as a low-barrier service shows a poor understanding of barriers for people at risk.

Is a service opened in a void truly voluntary? Or is our bar set at ‘better than nothing?’

In the current climate, transit police are cracking down on people who can’t pay their fare, with people even being thrown in jail for warrants placed on them for unpaid fines. Combine this with the forced treatment model internally planned by the UCP, and we could easily see Charter rights violated for unpaid transit fare.

Risks created by virtual prescribing

The risks facing people in the custody of police or corrections are significant: top among them, that people are at highest risk of overdose or drug poisoning death after being forced into abstinence. Incarceration is one way this occurs.

We also know some incarcerated people are denied access to opioid agonist treatments (OATs). In Timothy James McConnell’s case, lack of access to OAT is believed to have driven his 2021 suicide inside the Edmonton Remand Centre.

Failing to provide people in custody with standard-of-care medical therapies is not acceptable. Is VODP meeting that need?

We don’t measure, so we don’t know.

Conversely, what conversations are taking place across jail cell bars? Are people in detention being made offers they can’t refuse? Are some treatments being unduly promoted over others? Recall that Indivior, which sells the two fastest-growing OAT drugs in Alberta, has lobbied the UCP government since 2020.

For health care providers, there’s no line of sight once a patient is pulled into the criminal legal system — no visibility through the prescribing database or sharing of medical records.

And it works both ways: someone exiting the carceral system needs to be safely reinitiated and connected with supports and prescribers in community. But people are being released from detention with nothing – no bridging scripts, no appointments booked, no records of care during detainment.

This all adds up to increased risk of overdose and death.

How do we improve transparency?

There’s no question that virtual prescribing can improve access for certain people. But when that power is in the hands of the wrong authorities with no accountability, we can be certain it will get abused.

Let’s return to the evaluation study of the VODP published by the program’s medical lead, Dr. Nathaniel Day. (Incidentally, the same Dr. Day who openly mused about forced abstinence as a UCP government witness during Ophelia Black’s court case.)

Earlier, I noted the glaring void under the “Competing Interests” declaration in the study. But even taking the study at face value, there are more problems: the study claims 58% (12 month) and 90% (6 month) retention rates, but only followed 440 patients of 1522 total people enrolled in the program. This almost certainly creates selection bias in the authors’ conclusions.

Put succinctly, we’d expect retention rates to be high for the clients who are retained in the program. The authors say it themselves:

“…because clients in the study sample were individuals who remained in treatment and were agreeable to completing assessments they may have also had more positive outcomes.”

The authors also acknowledge the lack of comparison group in the study design (i.e., a point of reference over which virtual prescribing interventions directly show an improvement) and bias from losing patients to follow-up — for example, how many of them dropped out of the program after a serious overdose?

Yet the study’s abstract — the only section most people read — emphasizes:

“90% of the study sample remaining in treatment over 6 months… Clients reported high levels of satisfaction (90%) and outcomes reflected reductions in drug use and overdose as well as improved social functioning.”

Dr. Day’s self-evaluation: fit for the pit.

At a high level, the public and the health care system should at minimum know:

- who is referring patients into virtual care,

- what are the demographics of people asking for and accessing virtual care,

- what follow-up records are being maintained,

- what actual retention rates look like (could be <30% by Dr. Day’s counts),

- how patient experiences are guiding quality of service,

- whether referrals elsewhere are being made, and

- why people are pushed out of programs — are we introducing survivorship bias?

That is: are we building a system of care into our “recovery-oriented system of care?”

Addiction and mental health care is already siloed: residential facilities don’t report to a regulator, so it’s impossible to know how people move through the system. And the “treatment” modalities at these centres are highly heterogeneous, with many facilities still not allowing opioid agonist treatments. Even for those who indicate they accept OAT medications, it isn’t clear if pressure is placed on clients to taper off.

We don’t measure, so we don’t know.