Alberta hits new peak in opioid poisoning deaths

A year ago, discussions stalled on new overdose prevention sites at Calgary Drop-In and Alpha House. As drug poisoning resumes its upward spiral across Alberta, Calgary shelters are being hit hardest.

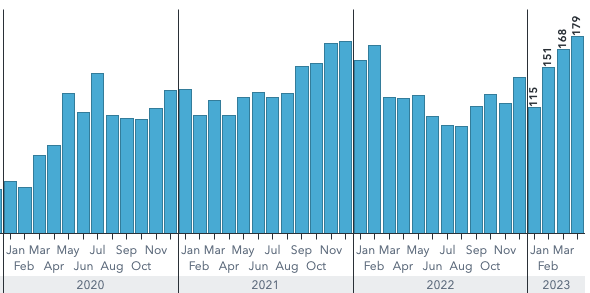

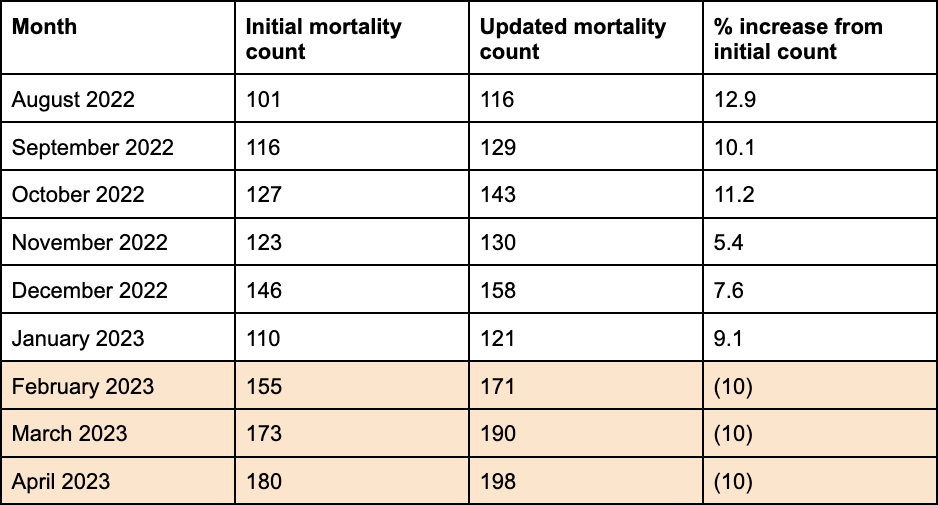

In January, two months before the UCP released its data, I predicted that December drug poisoning deaths would reach 160 and signal a turn to new peak poisoning mortality rates in Alberta. Yesterday’s provincial update, which was not announced by the government, increased December’s mortality total to 158 and finally revealed data for February, March and April.

The forecast of 160 deaths in December was based on a rapid spike in poisonings under supervised consumption in Calgary. It’s a good proxy measure because it reflects drug supply toxicity — the main reason so many people are dying. We’ve since realized EMS dispatches can also be used for mortality forecasting while we wait on the next politically expedient moment for the UCP to share mortality data.

Together, these predictors told us we’ve entered a new peak in drug supply toxicity in Alberta. Yesterday’s announcement confirmed it: Alberta experienced its highest and fifth-highest opioid poisoning mortalities in April and March.

Later, when updates are made to February-April drug poisoning mortalities, we should expect 10% increases from the current reporting. These numbers will place April and March at the highest and third-highest counts for total poisonings involving all drugs.

What is going on here?

A generous read on this situation is that this government’s “recovery-oriented” interventions have no real bearing on drug poisoning outcomes, and Alberta remains completely at the mercy of fluctuations in the composition and strength of the unregulated drug supply.

However, since we were forced to listen to “mission accomplished”-style announcements from provincial and federal politicians around the temporary and overstated drop in deaths through summer 2022, it’s worth examining several provincial policy decisions since this upturn resumed last fall.

Failure to build overdose prevention into shelters

Last summer, there was a brief public debate over whether Calgary Drop-In should build an overdose prevention site. At the time, staff were responding to over a hundred drug poisonings every month. After an astroturf business coalition mounted a negative campaign and the East Village Neighbourhood Association made their feelings heard, the project was shuttered and later replaced with $4 million to build a detox centre at the Drop-In.

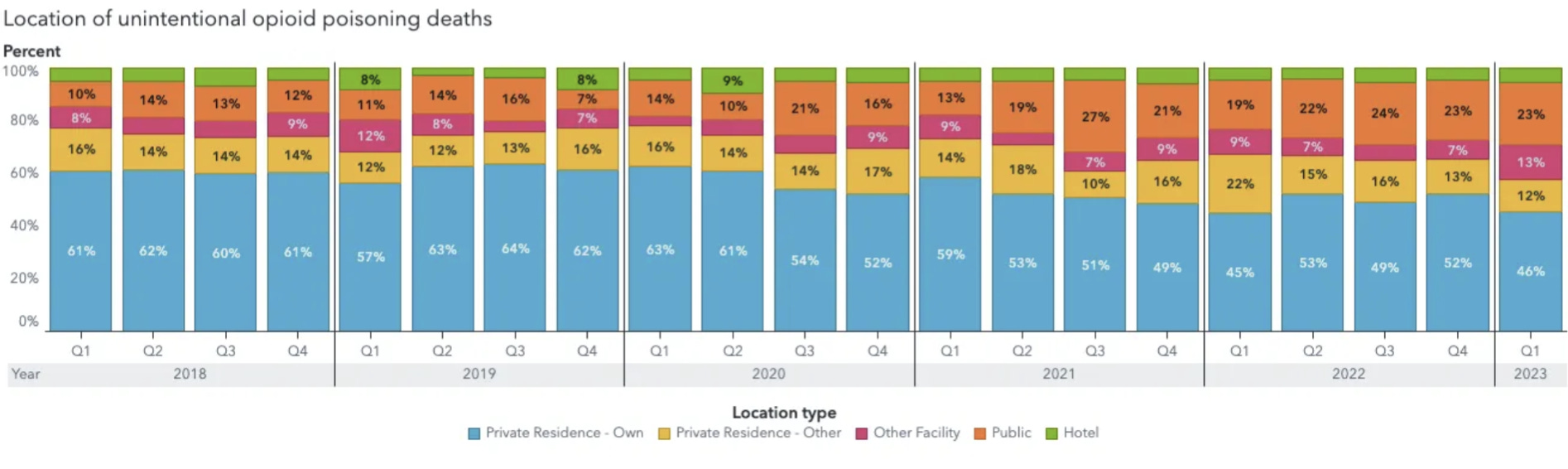

In April, Calgary Drop-In Executive Director Sandra Clarkson revealed that drug poisoning nearly tripled year-over-year at the Drop-In through the first four months of 2023. This adds up: examining the locations of drug poisoning deaths in Alberta for the first quarter, the largest proportional increase — nearly doubling the previous quarter — is seen in “Other Facilities.” That mainly means shelters. Calgary and Lethbridge are leading the way with 17% and 19% of opioid poisoning deaths occurring in “Other Facilities.” This is in contrast to 11% in Edmonton and a provincial average of 13%.

It’s hard to overstate the devastation resulting from the failure to open overdose prevention capacity at Calgary Drop-In. While this discussion is closed for now, people can rally behind Alpha House’s parallel effort. Beltline folks: consider informing your neighbourhood association or city councillor you want to see these move forward.

Elimination of safe supply

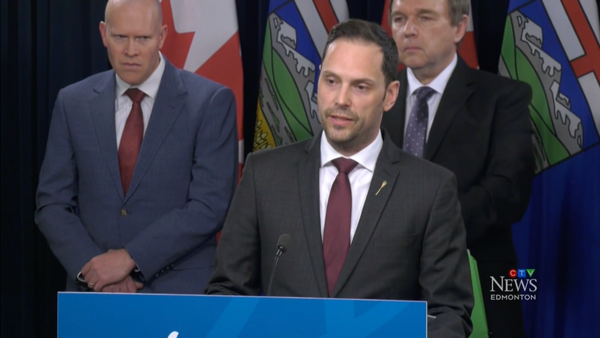

Two months after the formal cancellation of the Drop-In overdose prevention site, the UCP announced the Narcotic Transition Services (NTS) in parallel with an announcement including Dr. Robert Tanguay. Tanguay helped drive the abysmal 2020 Alberta Supervised Consumption Services Review, which helped the UCP justify closing one-third of the province’s supervised consumption booths.

In this parallel announcement with Tanguay, the UCP declared open season on psychedelics-based addiction and PTSD treatment. Tanguay’s company, the Newly Institute, sells its psychedelics-guided services to Calgary Police, so it’s a bit weird that he’s now a sitting Calgary Police Commissioner.

Anyways. The Narcotic Transition Services was effectively a framework by which to end opioid prescribing by family doctors and nurse practitioners and make safe supply less accessible for individuals. The measure targeted take-home doses of hydromorphone, the closest thing to safe supply that Alberta had until this point. With the help of lawyer Avnish Nanda, Ophelia Black obtained a court injunction to keep her take-home prescription, but dozens of others were forced into centralized facilities, which have largely failed to materialize. This means most of these folks are having to travel far — in many cases multiple times a day — to access this high-barrier, over-medicalized care.

Like I said, the point was to eliminate access.

The NTS was implemented between December and March, so everyone who previously had access to safe supply was transitioned into the central Opioid Dependency Program facilities by the end of that period. One wonders how many of those folks are counted among the mortalities in recent months.

Police crackdown on unhoused people

A month after the NTS announcement, the UCP convened public safety task forces in Calgary and Edmonton, comprising UCP MLAs and UCP-friendly city councillors. Calgary Mayor Jyoti Gondek had some time to prepare her response as the Calgary task force announcement was made several days after the one in Edmonton, but Edmonton Mayor Sohi was unimpressed with the rollout:

"I was not made aware of it. We were not, in any way, included in the creation of the task force" -Edmonton Mayor Amarjeet Sohi

The purpose of the task forces was, as I suggested in February, to augment city police powers and circumvent legal barriers to forcing unhoused people into addiction treatment (perhaps more accurately called conversion therapy) or locking them up for any available reason, such as outstanding warrants.

At the time, I described it as an election strategy to disappear unhoused people from the public eye. Judging by the election result, which followed a classic law-and-order campaign, the strategy was successful.

Many of us tried making noise about the deployment of more police while housing and safe supply remained inaccessible. Since then, a publication was printed that those involved with the task forces will surely do their best to ignore: it shows how police drug busts drive increased drug poisoning deaths in the immediate vicinity for weeks afterward.

It is not hyperbole to state that increasing police presence in the downtown cores of Alberta cities likely contributed to the rise in deaths we’ve seen through 2023.

Failure to decriminalize drugs

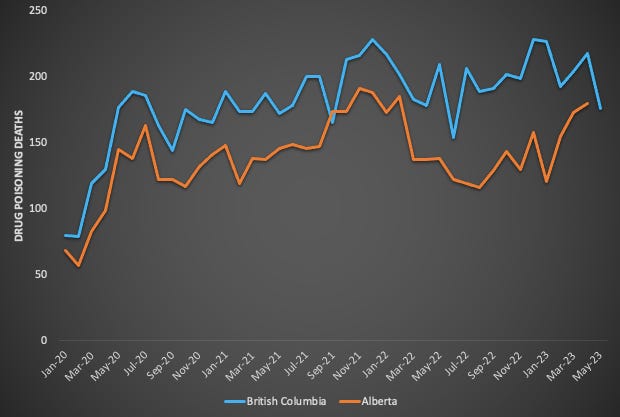

On February 1, the same day a dozen police hit the Edmonton City Centre Mall with a new lease on the lives of unhoused people, British Columbia’s decriminalization of drug possession under 2.5 grams took effect.

The two provinces have tracked closely on drug poisoning deaths for years. Whenever one goes up or down, the other tends to follow. If decriminalization is improving people’s ability to keep themselves safe while using drugs, this might be showing itself already.

Regardless of its impacts on mortality, decriminalization is the humane policy choice. But Alberta is stepping the other way: increasing police interference in the lives of people already struggling without housing, food security or access to regulated drugs.

Every politician, industry profiteer and pundit capitalizing on this crisis created through repeated policy choices should be held publicly accountable. Let’s begin this work in Alberta.