Legal review of Health Canada decision could sever the anatomy of the overdose crisis

A lesser-known legal case involving the Drug User Liberation Front could finally permit meaningful intervention in the toxic drug supply.

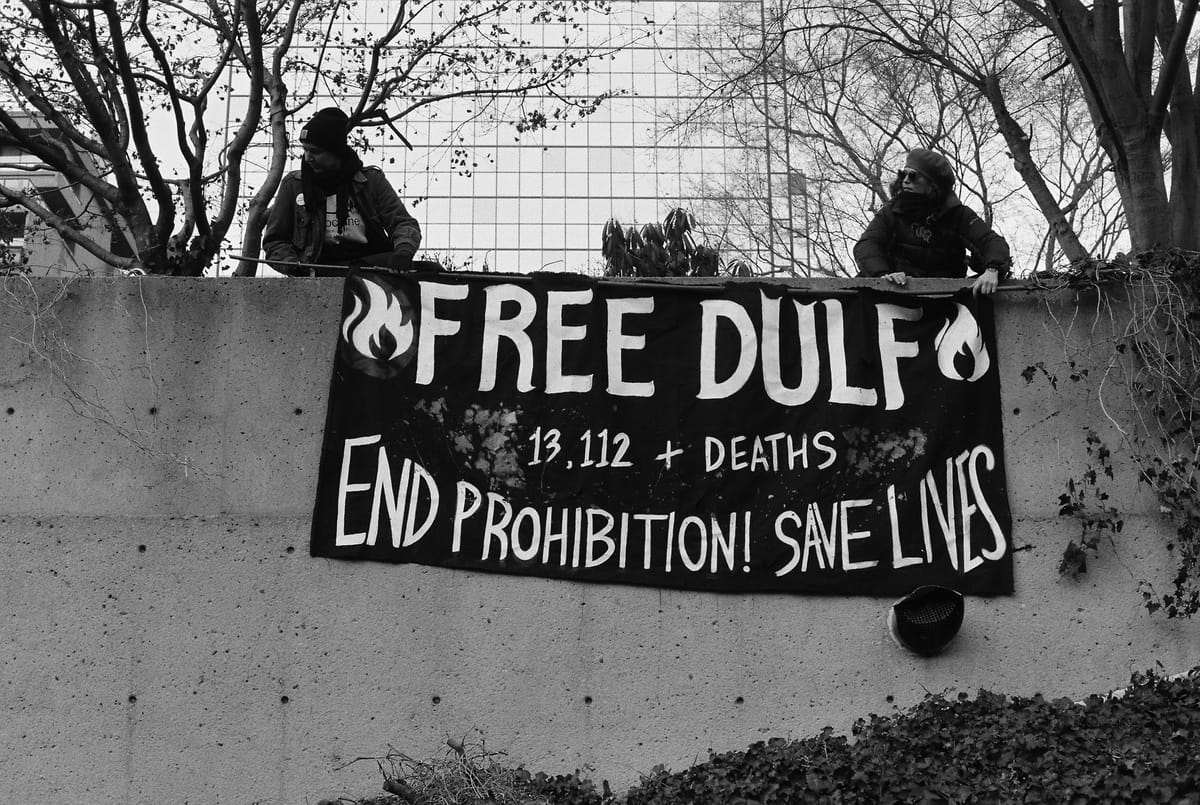

On March 7 and 8, the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF) and co-plaintiffs Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) will hear a judicial review of Health Canada’s 2022 decision to deny their application to legally run a safe supply compassion club during the drug toxicity crisis.

Unlike DULF’s pending criminal charges – arguably a spectacle for police and politicians in a provincial election year – this administrative challenge is being led by the two drug user rights groups.

In 2022, DULF and VANDU appealed Health Canada's denial of their request for a legal exemption from the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) to operate a compassion club. This is the same exemption that upholds “decriminalization” in BC and the operation of safe consumption sites across the country.

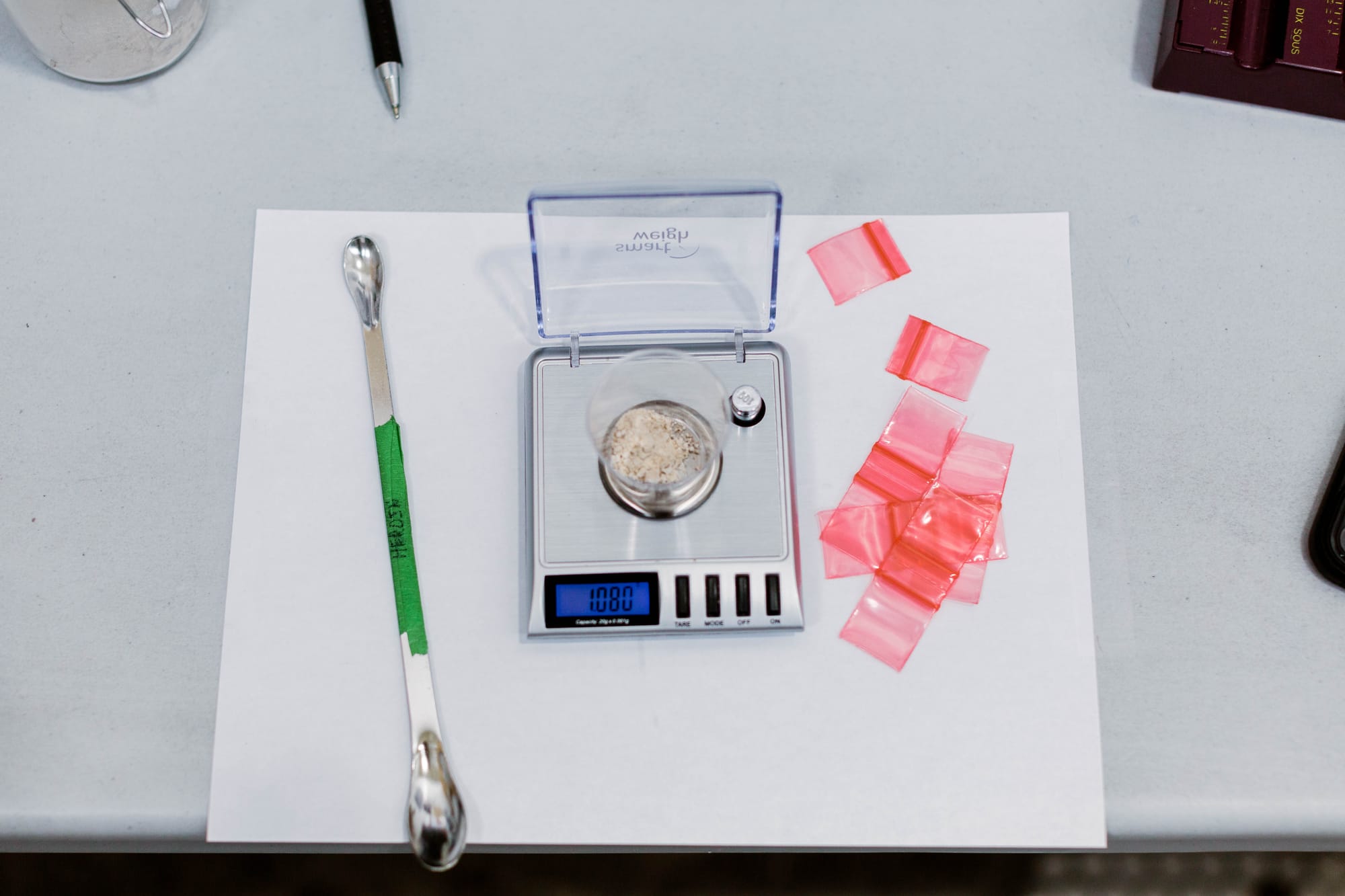

Compassion clubs are non-medicalized drug distribution sites that offer predictable, tested and labeled substances to members who already use them, at appropriate potencies and the most useful points of community access. DULF’s preference is to distribute drugs produced in a legal pharmaceutical context, but, forced into a corner without government permission, they have been willing to purchase from dark-net markets.

In short, DULF and VANDU winning the appeal could set a precedent for legal compassion clubs in Canada.

DULF requested the exemption in October 2021. Since then, thousands more people have died from the drug toxicity crisis. In 2022, DULF opened a compassion club anyway.

But in October 2023, the compassion club was raided and its founders, Jeremy Kalicum and Eris Nyx, were arrested. They were since released, only to be kept in limbo about whether they will face charges. The club has been shut down since the police raids, putting the former membership at greater risk of overdose and other harms from the unregulated supply.

“I was very proud of actually being part of that,” says Howard Calpas, a member of the compassion club and long-time advocate for harm reduction measures in Vancouver.

Calpas believes Nyx and Kalicum “did a lot of good for a lot of people.”

DULF launched a compassion club, ran it for a year, tracked and evaluated the program, showed extensive positive results, and were subsequently raided, arrested, and released. In that same time, Health Canada has created an endless feedback loop of bureaucracy.

The International Journal of Drug Policy published DULF’s findings last month. Among several positive outcomes, there were zero deaths among the club’s membership and major decreases in non-fatal overdose.

“No, I was not surprised. I knew that was going to happen,” says Calpas, comparing DULF’s supply to the street supply with multiple psychoactive components and cutting agents, “and all kinds of nonsense.”

“We did not lose one person,” emphasizes Calpas.

Non-fatal overdoses are much more common and have contributed to strains on services, including harm reduction workers, firefighters and paramedics who have been working in a crisis context for almost eight years.

To date with little exception, mostly only physicians have been permitted to allow (or deny and de-prescribe) people access to a regulated drug supply. Prescribed alternatives programs have had positive effects for the less than 5% of people who use drugs that they reached at their peak.

The medical system is surveillance-oriented, and to date has only focused on a small, select number of drugs – despite the diversity of the province’s estimated 225,000 people who use the unregulated drug market each year.

Calpas is just one example of how use patterns change drastically from person-to-person.

“I don’t use heroin like most people. I don’t inject it and I don’t smoke it,” he shares. “I take it orally. What I would do is, I would take 2 ½ points, put it under my tongue, and let it dissolve, and if there was anything left, I would wash that down with coffee.”

Calpas says this would last him for 12-16 hours and help him manage the chronic pain he has, generated by a long list of medical diagnoses linked to his back and spine.

In November 2023, the BC NDP government outright rejected intervening in the unregulated drug supply outside of the medical system, despite pleas from the Chief Coroner and a team of experts that made up the Death Review Panel to take these measures reduce deaths – a deliberate strategy that will permit the crisis to persist and worsen.

Section 56 Exemptions

If the federal government is not going to grant a CDSA exemption to a small compassion club now – to see if a novel intervention could help end a crisis of mass death – when will they?

In an affidavit for the upcoming court case obtained by Drug Data Decoded, Carol Anne Chenard, Director of Health Canada’s Office of Controlled Substances, affirmed that “public health and public safety objectives of the CDSA” is a common consideration for granting exemptions to the framework.

Health Canada declined an interview but provided a written statement that reiterated Chenard’s claim that they are “taking into account all relevant considerations” of the CDSA, “and evidence of potential benefits and risks or harms” when deciding on Section 56 exemption requests.

The statement added that “Health Canada is aware of the [DULF] publication from the International Journal of Drug Policy and is reviewing it,” but would not be providing further comment based on the upcoming court date.

The anatomy of a crisis

There is an arc to how and when the drug toxicity crisis started in BC, the province impacted hardest so far in Canada.

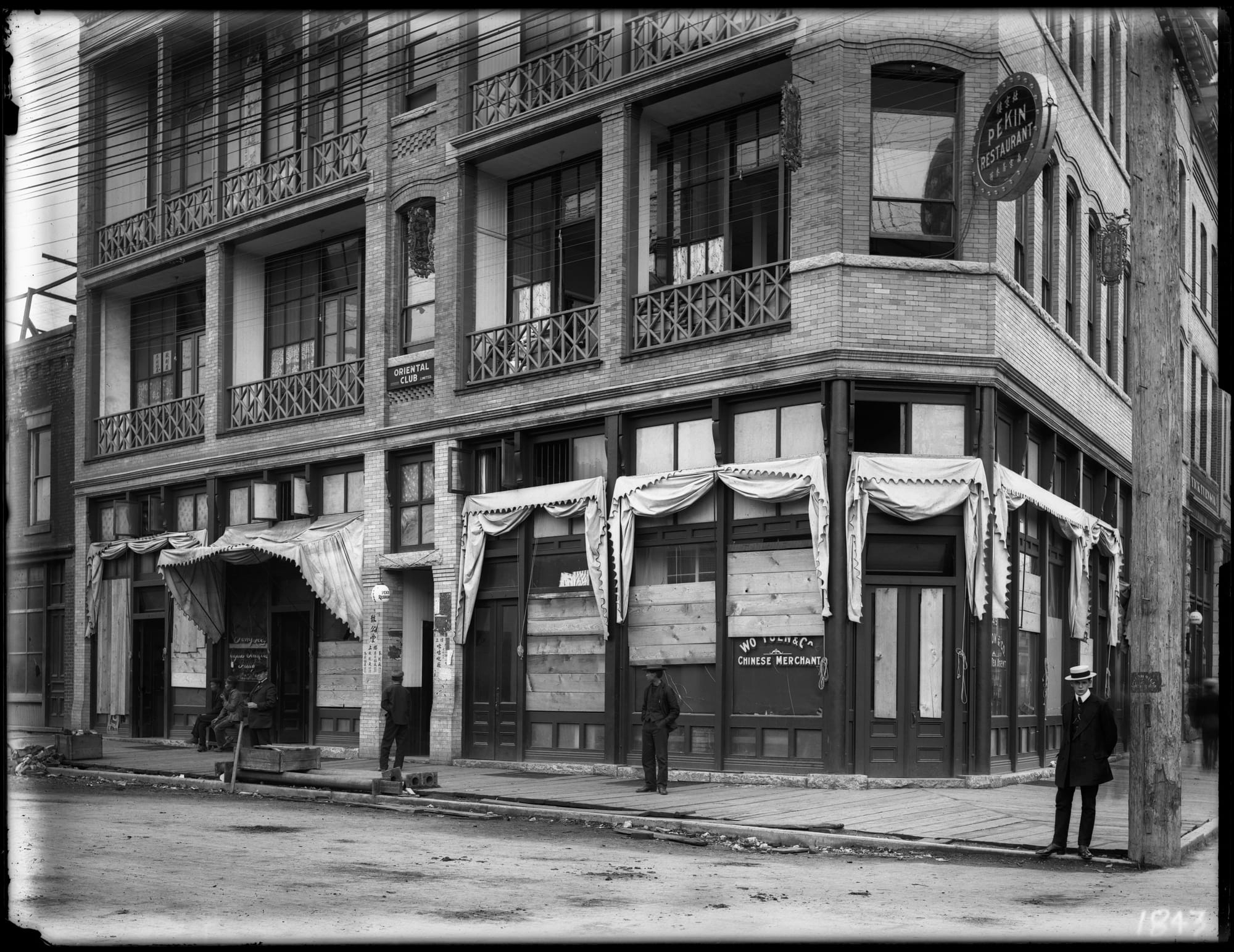

You could go back 110 years to the anti-Chinese Opium Act, which, as VANDU organizer Vince Tao writes, “was legislated on the heels of the 1907 anti-Asian race riot that burned Vancouver’s Chinatown to the ground,” and expanded prohibition beyond 1800s iterations of the settler colonial Indian Act.

We could then trace the history of drug prohibition through successive crackdowns on the unregulated supply, along with the modernization of surveillance evasion and synthetic drug production. Whether we call it the war on drugs or the Iron Law of Prohibition, the unregulated supply and market have become volatile under this framework.

In the mid-2010s, Canada’s political class, including some medical practitioners, began expressing concern about the over-prescribing of opioids and called for “stemming the flow of illicit opioids into Canada” and more stringent control over prescriptions to high-potency opioids (waves of international heroin shortages had already started).

In keeping with the default militarization of the war on drugs, meeting these shifts required increased enforcement and surveillance.

By 2016, people who use substances, including those who were previously prescribed opioids, moved from having direct and diverted access to a regulated market to being compelled to source their drugs from the unregulated market.

Predictably, overdose death rates started to climb. By now, the crisis has been deemed by some to be a forever emergency in BC – and the supply is as toxic and unpredictable as ever.

Compassion clubs against drug war violence

After Vancouver Coastal Health management defunded, and police raided the DULF compassion club last fall, five club members published an open letter. The members expressed their belief in the compassion club for their own safety, despite its legal precarity.

The group wrote, “We do it because we have to: to save ourselves, to save each other, to create a more just and equitable present and future.”

Despite DULF’s compassion club work being made public through many media stories, including features in Time Magazine and The Guardian, it was not until the compassion club released its preliminary results that the police and province abruptly moved to shut them down in October 2023.

Just as Kalicum, Nyx and the DULF membership began to clearly reveal the cracks in society’s drug war logic, institutions and structures who have long upheld prohibition mobilized against them.

As social worker and PhD student Jenn McDermid stated in The Bind the day after the raids, “DULF actually tried to undercut the toxicity of the supply, and these institutions [invested in the status quo] likely saw that as a threat.”

The sudden undoing of DULF closely resembles concepts of backlash politics, defined in part by the resistance generated by a social movement crossing over from periphery to success in challenging dominant discourse, beliefs and policy.

Legal community-based compassion clubs could unravel more than a century of societal inertia against substances that are defined by their prohibition, as well as the people who use them. This inertia is ultimately rooted in colonialism, racial capitalism and carcerality.

And though Health Canada, the province and the police have been successful floodgates for continued prohibition and its violence – if a single administrative review can open them up, drug war power will face constant existential threats of being undone.

As Karen Alter and Michael Zürn theorize, backlash dynamics can be destabilizing and fundamental change can follow – that is, the drug war could be on its death rattle – but the outcome likely depends on what happens next socially, politically and judicially.

NDP-United Against Drug User Lives

The NDP, who have governed BC since 2017, have claimed over the years that they are combating the drug toxicity crisis by pouring boatloads of cash and resources into the provincial response.

But the claims are janky in practice.

Under the BC NDP, the government has invested most heavily in issues adjacent or loosely linked to drug toxicity – a small proportion of these resources have been used toward supply intervention. Within the fraction that has, much of it has gone toward non-enforceable prescribing guidelines that meet the needs of few people.

The NDP, along with the opposition BC United led by Kevin Falcon, have been consistent in conflating privatized treatment sites with drug toxicity, despite the fact that outcomes are not measured at these opaque businesses, nor are deaths. Most relevant though, these sites do not have a noticeable impact on the toxic drug supply, which, sadly, can make attending these inpatient treatment sites more dangerous for people seeking support in changing their use patterns.

Alberta sees similar patterns in a system Drug Data Decoded editor Euan Thomson called, “a flimsy raft in a storm of toxic drugs” last month. A Globe and Mail headline from the week prior read, “Alberta drug deaths soar to highest level ever recorded.”

More recently, NDP Premier David Eby seemed to give up on the charade altogether, telling the Northern Beat, “Recovery really is the only way to guarantee that someone is going to be less likely to overdose and die if they are not using these drugs. Even prescribed supply is highly toxic and potentially fatal.”

To address the drug supply, address the drug supply

“It was the easiest decision I’ve made since I got elected,” then-Vancouver City Councillor Jean Swanson told Filter in 2021, after joining DULF and VANDU during a free, community distribution of tested and predictable drugs.

More than 13,000 people have been killed by the unregulated drug supply in BC since it was formally declared a public health emergency.

A long list of supporters, the coroner’s expert Death Review Panel, and plenty of evidence for needed novel interventions into the drug supply to reduce the death rate all support DULF’s model. And so does Calpas.

“It would be fantastic, in my eyes,” Calpas says of DULF and VANDU potentially overturning Health Canada’s decision, and having the exemption granted.

“My own family thinks it's a wonderful thing. They saw how it helped me.”