The Alberta Drug Model is a Christian institution: Part 1

At least half of long-term addiction care beds are Christian and almost all are 12-Step abstinence-based. Part 1 of a series on Alberta addiction services.

Note: this piece was adapted and reprinted by The Tyee. For that version, head to their site!

On March 12, fierce drug policy author and journalist Maia Szalavitz published a stinging indictment of the Christian domination of addiction treatment across the United States. Her New York Times piece describes the 12-Step addiction recovery model, which she asserts helped her become abstinent in the early 90s.

She then asks why this Christianized approach consumes such a large slice of the funding pie.

I was recently provided a list of every detox, short-term and long-term residential facility across Alberta that details each facility’s approach and offerings, maintained by senior staff at Alberta Health Services Mental Health & Addictions to help clinicians make informed referrals for people seeking help.

From this document, I calculated the proportions of various treatment modalities, including abstinence requirements, Christian approaches and the use of 12-Step.

With four people in Alberta dead each day from unregulated drugs that abstinence strategies do little to address, the data are shocking.

It’s important to note that I am not against any voluntary coping strategy, even if it lacks evidence: people should be allowed any approach they feel will do something positive, whether it’s a crystal necklace or crystal meth (the latter of which, in oral form, is both available and evidence-based for treating ADHD).

If you are going to comment on my article, please read it carefully. I am not saying that some people don't benefit from AA; I'm not saying AA is bad; I'm not saying atheists can't benefit. I'm saying it shouldn't be paid for via rehab or mandated as the only way to recover.

— Maia Szalavitz (@maiasz) 6:16 PM ∙ Mar 13, 2023

What should be publicly funded is a different story entirely. Public dollars should be limited to evidence-based treatments and pilot testing. In the press release explaining our protest of the Alberta Recovery Conference in February, definitions of recovery and treatment were contributed by the strategic communications co-ordinator of the Alberta Alliance Who Educate and Advocate Responsibly, or AAWEAR, a group created “by and for people who use drugs in Alberta.”

“‘Recovery’ is a non-linear, socially constructed practice, and success is contingent on an individual’s goals related to drug use. ‘Treatment’ is an evidence-based medical practice that insists on verifiable, objective medical outcomes, evaluation, accountability and voluntary consent,” the co-ordinator wrote.

Unfortunately, 12-Step abstinence-based approaches do not make the grade for treatment, particularly as the extremely high rate of drug use resumption following current treatment modalities spells death for countless people. And we still don’t have the foggiest evaluation data for Alberta’s ‘recovery-oriented’ system of care, as detailed in our June 2022 open letter, so it’s impossible to say what is even working.

Formats of care

The AHS document categorizes the facilities into five groups for substance use care:

- Withdrawal Management / Detox

- Intensive Adult Concurrent Disorders Treatment

- Intensive Adult Substance Use Treatment

- Indigenous / NNADAP Substance Use Treatment

- Supported / Transitional Recovery.

Here in Part 1, we’ll focus on Supported / Transitional Recovery, which represents both the clearest delineation of government ideology and the area of greatest provincial investment. Among these facilities are the “therapeutic communities”.

Spaces and beds

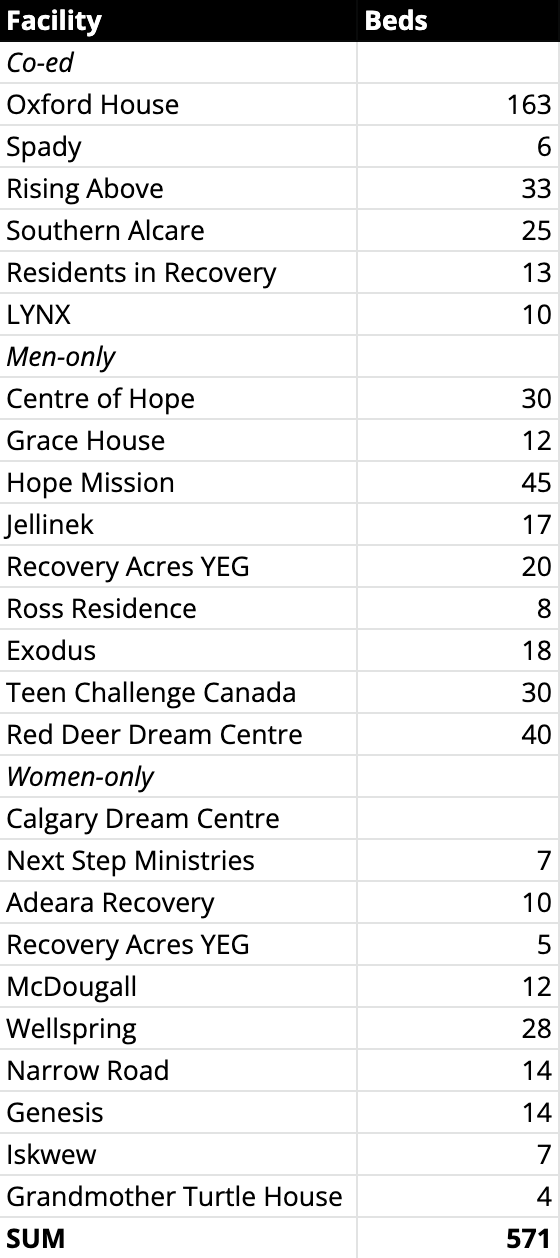

The AHS document counts the beds at each of 25 facilities across Alberta. These range from 4 at Grandmother Turtle House to 163 at Oxford House. No bed count is provided for Calgary Dream Centre. Typically, we’d be more interested in spaces: how many people can use a bed over a given year based on average length of stay. Since length of stay varies from a few months to indefinite with Supported / Transitional Recovery, we get a better look at the overall picture by focusing on beds.

One facility’s entry from the document is shown below. I’ve redacted bed count for anonymity. In this case, the facility was counted as abstinence-based and Christian but not offering 12-Step (even if it likely does). Therefore, the data that follow are under-estimates of the Abstinence, Christian and 12-Step focus of the facilities.

The Alberta Model is a Christian abstinence model

In her New York Times piece, Maia Szalavitz outlines the 12 Steps:

To put it bluntly: 12-Step is Christian. It is also explicitly abstinence-based.

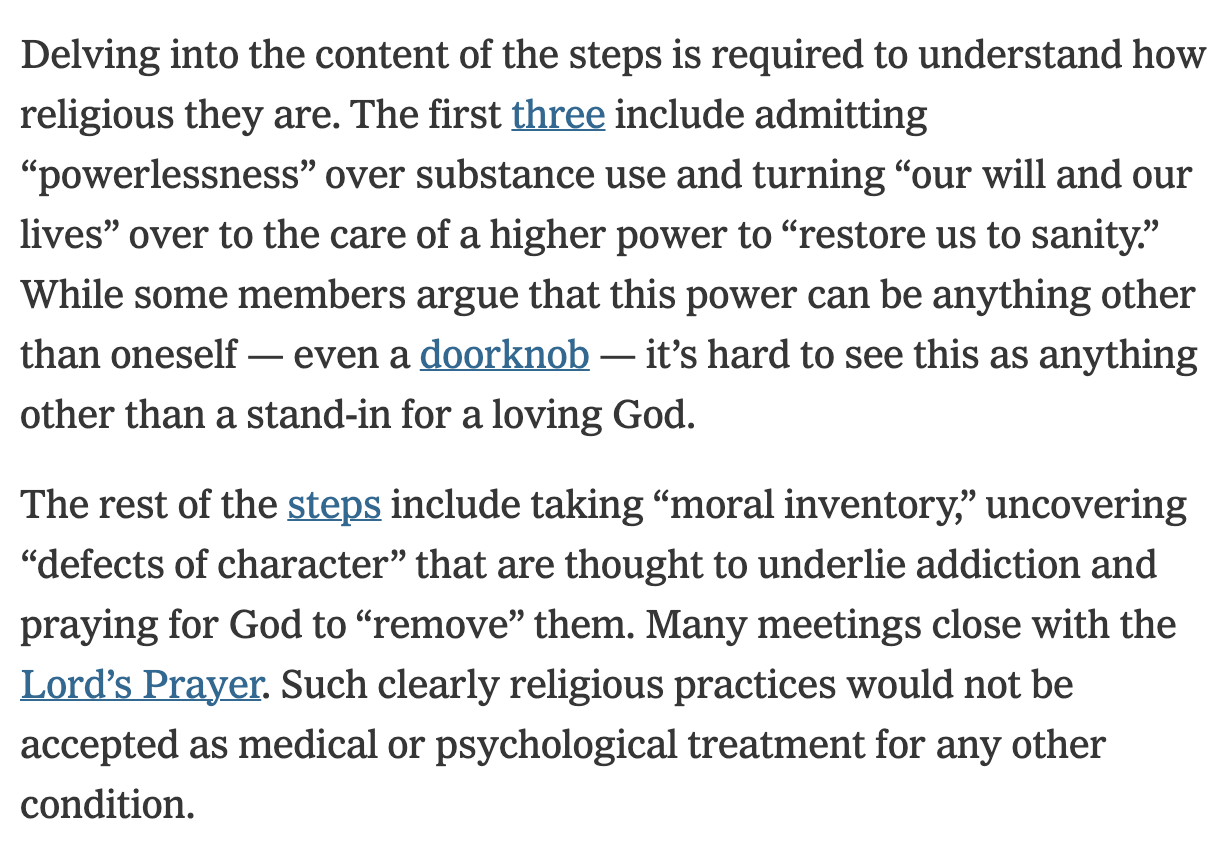

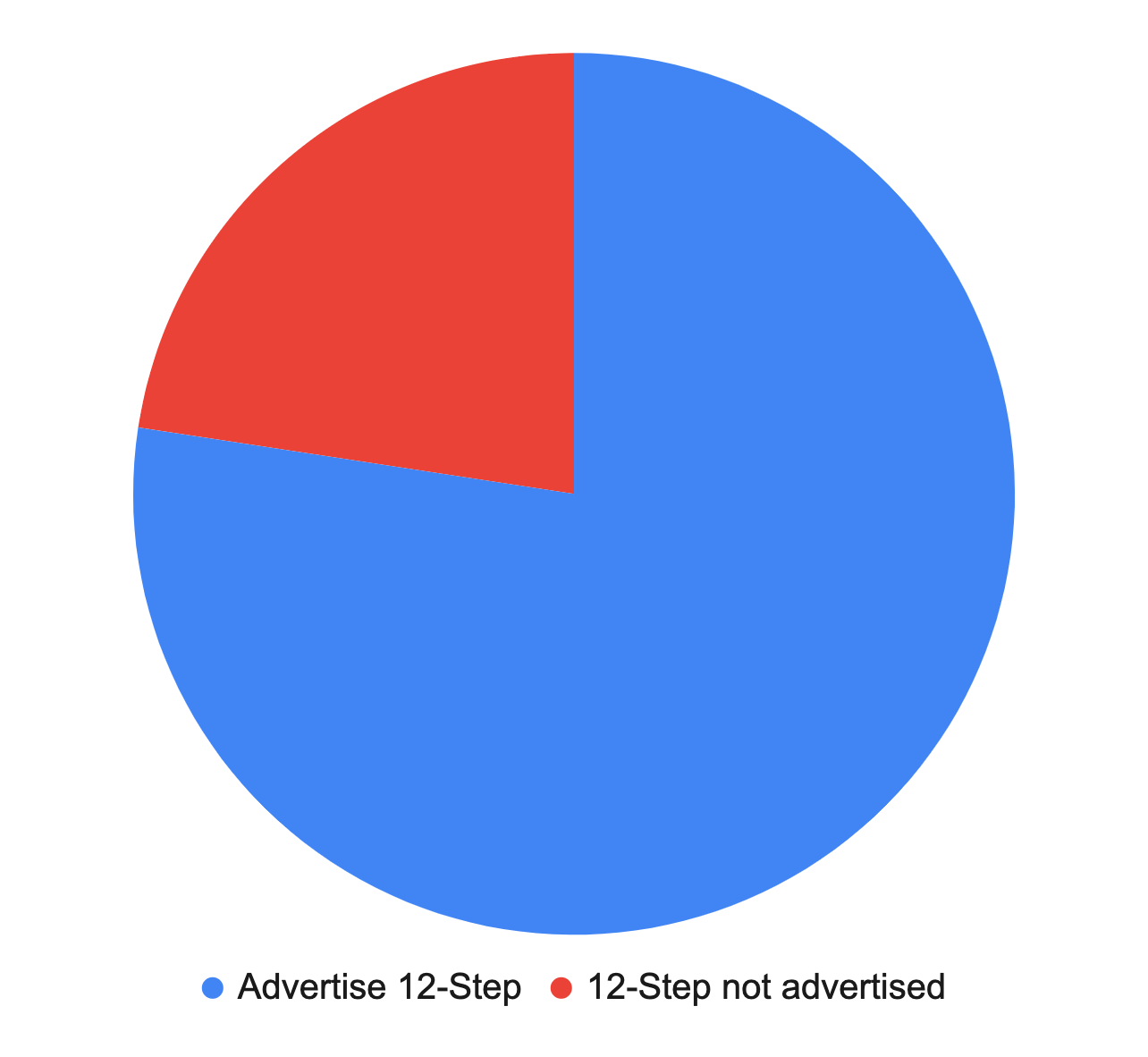

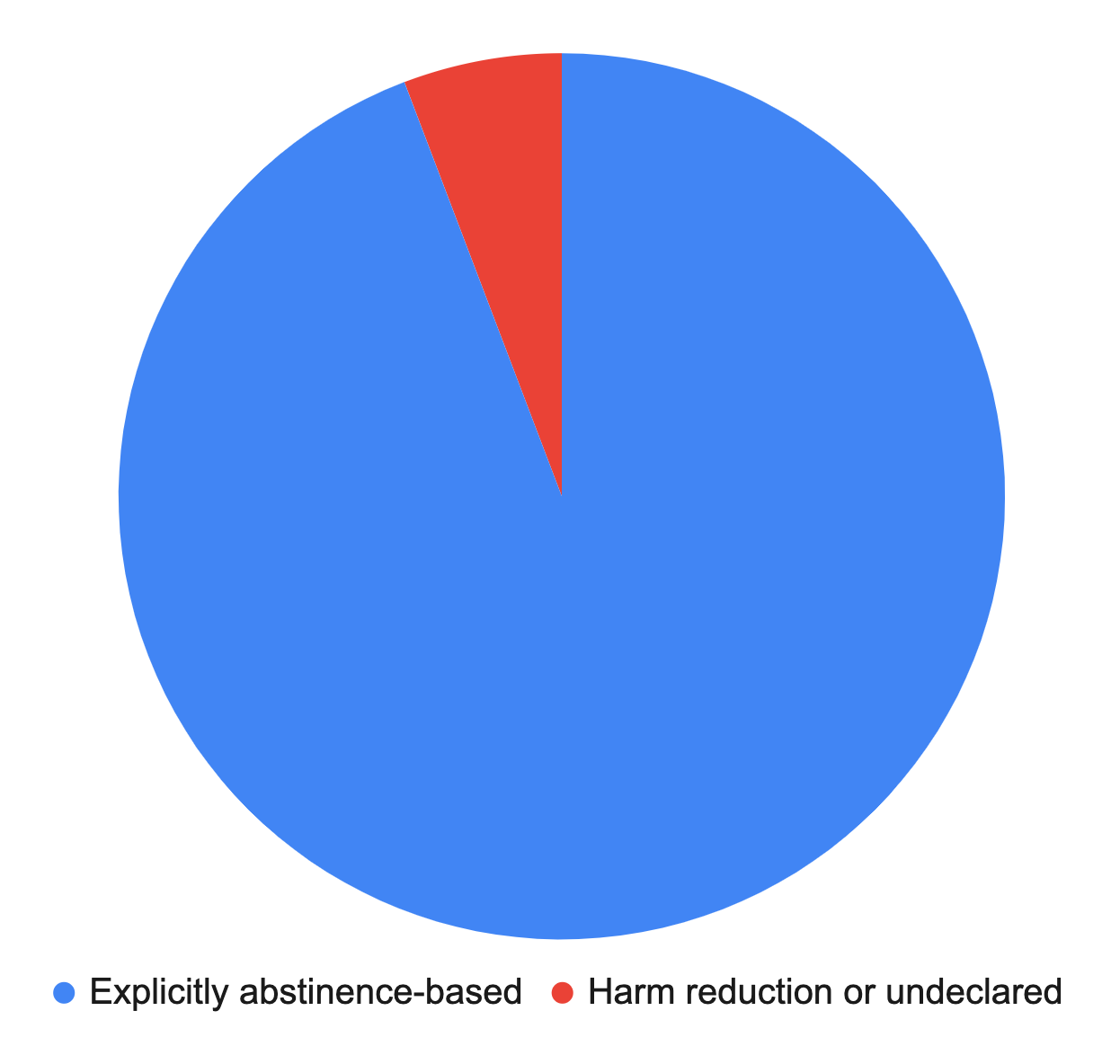

According to the AHS document, at least 47% of the beds are in facilities describing themselves as Christian or “faith-based.” Meanwhile, the 12 Steps are used in facilities representing 77% of the total beds, and abstinence is the focus of facilities representing a whopping 94% of beds. So much for harm reduction in Alberta.

This is problematic. As Szalavitz puts it: To make real progress in fighting overdose and addiction, we need to separate medical care and religion in treatment, as we do for every other health disorder. And given that 12-Step groups are freely available and ubiquitous, why are we funding this modality with public dollars?

Meanwhile, several facilities occupying nearly 20% of the total beds employ the Genesis Process, which can only be described as religious indoctrination. Why are taxpayers funding facilities to educate people on a “biblical understanding of what causes their self-destruction”?

A suspicious mind might wonder if our institutions are working to drive people into Christianity at their most vulnerable.

Breaking loose

I recently translated several recent UCP overtures toward forced abstinence. We are entering a precipitous moment and it seems our institutions are fine to go along for the ride. It could take several forms, but many workers are already forced into abstinence by unwitting or uncaring workplaces. (Free evidence-based workplace substance use policy available here.)

Szalavitz explains an American legal precedent setting out the unconstitutionality of forcing workers into 12-Step programs for addiction because of their inherent religiosity. I am aware of only one sector in one Canadian province that has been forced down this road, after Byron Wood and maverick labour lawyer Jonathan Chapnick won their case against Vancouver Coastal Health:

I know people who are happy and healthy after participating in Christian 12-Step abstinence. For the most part, they shed the less useful stuff and hold onto what worked for them — as Szalavitz puts it, the active ingredient in their success is peer support, not the steps themselves, because secular groups seem to be similarly useful.

But for every story like that, how many are dead? We have no idea, because we have no data.

In Part 2, we’ll look at how detox and other facilities similarly limit options for people seeking help.