Survival of Alberta children forced into drug withdrawal is not monitored

The Alberta government has yet to release its proposed Compassionate Intervention Act but indicated in 2023 that the Act would extend existing legislation for forced abstinence of children to adults. Documents show that survival and other data are not tracked after children exit the system.

Note: Contents of this piece may evoke trauma among readers who have been involved with forced abstinence.

Documents obtained by Drug Data Decoded reveal that outcomes are not monitored for children forced into temporary abstinence from drugs through the Protection of Children Abusing Drugs Act, or PChAD – nineteen years after the legislation was enacted.

Key outcomes would include survival, overdose events, service access for substance use and involvement in the criminal justice system, in the medium and long terms.

According to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, children should have access to the "highest attainable standard of health." This becomes impossible if outcomes are not measured.

Meanwhile, children and their guardians have a right to informed consent. But without outcome measurement providing risks and benefits to the patient, a procedure fails to meet conditions for informed consent.

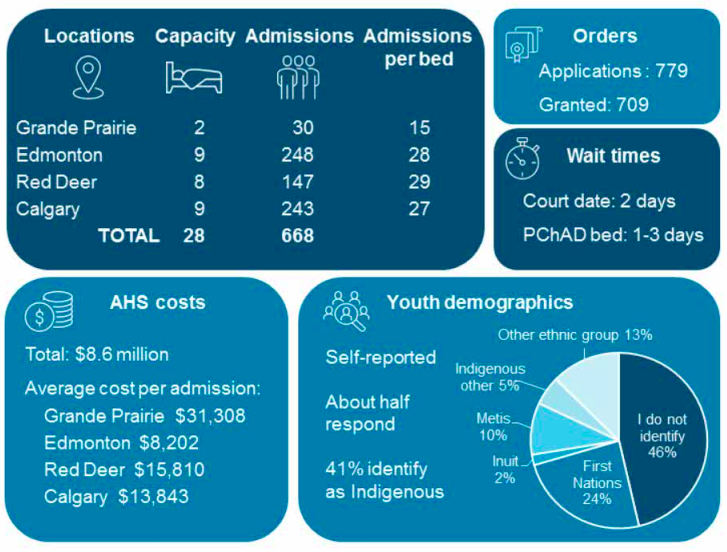

Furthermore, over 40% of children in the system are Indigenous, while Indigenous children make up only 10% of the total in Alberta. According to 2023-24 reporting by Alberta's Office of the Child and Youth Advocate (OCYA), nearly three-quarters of deaths among youths (up to age 24) in provincial care were Indigenous.

Without outcome monitoring, it becomes impossible to determine if there is a link between Indigenous PChAD admissions and deaths of Indigenous youths in provincial care.

PChAD allows parents and guardians to obtain a court order compelling children (below 18) into detox at a "protective safe house" without medical review. Alberta is the only jurisdiction that provides this unilateral power to guardians, and police are frequently involved to forcibly transfer children to detox sites.

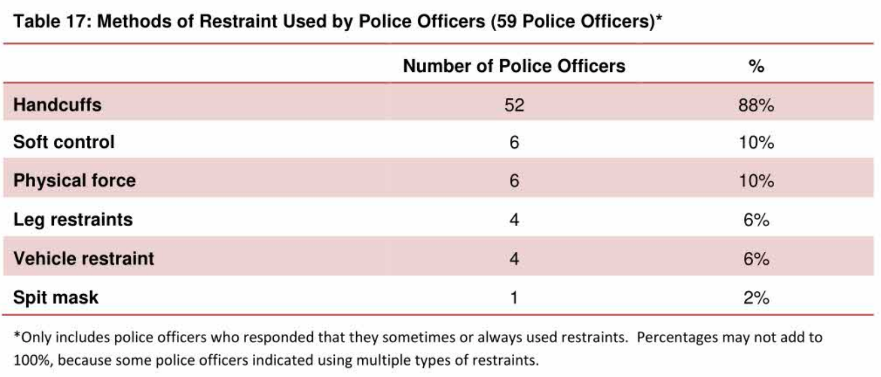

Of around 140 police officers interviewed by Alberta Health Services in 2017, 52 reported using handcuffs to restrain children during these renditions, while 6 officers reported using "physical force" and one reported using a spit mask.

In 2018, the OCYA reviewed the drug-poisoning deaths of 12 youths forced into PChAD, concluding that "the Ministry of Health should undertake a review of the Protection of Children Abusing Drugs (PChAD) Act and its policies, so the related services better meet the needs of young people and their families."

This review was completed in 2020, as detailed in the obtained documents, but was not made public. Instead of serving children and their families, the review was apparently used to design the government's forced abstinence legislation.

The Alberta government's proposed Compassionate Intervention Act, or CIA, is planned for 2025 and will allow "families and communities," including police, to compel adults who use drugs into abstinence. A month after The Globe and Mail uncovered these plans in April 2023, the government admitted that the CIA would extend PChAD "for families and communities to intervene if someone is a danger to themselves or others beyond youth." (Emphasis added.)

PChAD facilities can employ "social detox" or cold-turkey withdrawal on children. According to the International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy, this is a form of torture. The Canadian Research Initiative on Substance Matters (CRISM) states that "withdrawal management alone [abstinence only] is not recommended" for opioid withdrawal, instead recommending opioid agonist treatments like buprenorphine or methadone, under supervision of a medical professional.

Because of the evidence that forced abstinence puts people at higher risk of overdose death, the design of the CIA around PChAD raises critical questions about the safety of people who use drugs in Alberta. It also raises the question of how successive governments have allowed the country's most domineering system for youth substance use to operate unmonitored for two decades.

Alberta government reviews PChAD

In 2022, the government compiled a series of reports on PChAD, which staffers appear to have mined for legal structures that might empower family, police, courts or medical practitioners to compel adults into abstinence under the proposed CIA.

Several reports underpin the review team's findings, including a program evaluation by Alberta Health Services in 2017, Alberta Health's 2020 Final Report on PChAD and an evaluation by third-party reviewer ThreeHive in 2020, drawn upon heavily in the Alberta Health report.

One of the staffers on the Alberta government review team was Robert Murdoch. Drug Data Decoded reported in early 2024 that Murdoch was hired to oversee the implementation of forced abstinence legislation. Together, the review team's documents detail the degree to which PChAD operates on unscientific assumptions made by a broad swath of "stakeholders" alongside little program oversight or evaluation.

Specifically, each report flags lack of outcome monitoring as a key issue to be addressed. Alberta Health lists among its eight Minister-approved actions that Alberta Health Services was to "develop and implement short and mid-term outcome measurement tools for youth leaving the PChAD program."

This appears to have never happened. On February 17, Drug Data Decoded asked the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction and the Ministry of Health if outcome monitoring had been put in place, and if so, whether the data were publicly available. Neither Ministry provided a response, and online searches for the data were unable to locate any system monitoring.

Exit surveys conducted by Alberta Health with 12 youths led its report authors to the conclusion that "the length of detention is not long enough... Upon leaving the PChAD program, youth may have physically detoxed from substances but are not yet mentally ready and willing to continue their recovery journey and accept voluntary treatment." Alberta Health also interviewed 12 guardians of children forced into the system, who told them PChAD "did not work" for the children in their care.

The report by ThreeHive also called for an extension of the confinement period, despite only interviewing one (non-Indigenous) child and two guardians. The "stakeholders" interviewed in these reports, many of which were private recovery providers, were presented as unanimously in favour of subjecting children to longer confinement durations.

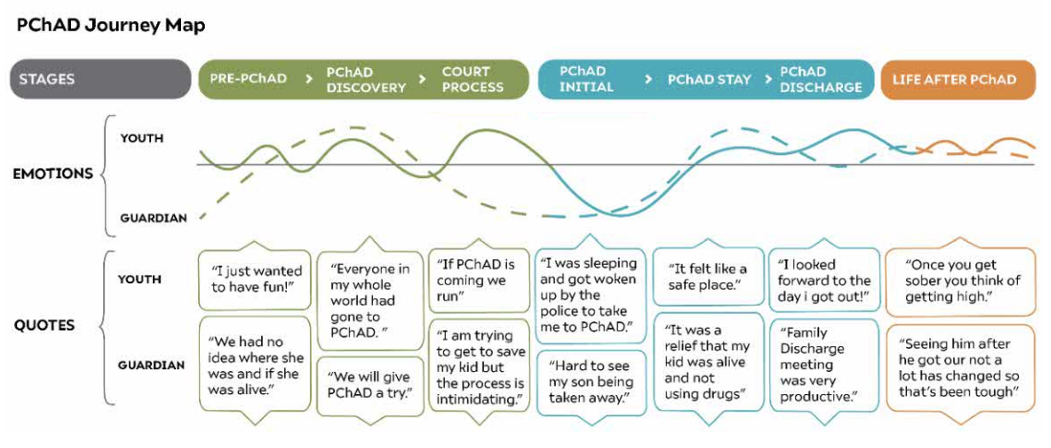

This recommendation, listed among the Alberta Health report's Minister-approved actions, is surprising in light of the PChAD Journey Map illustrated in the report's Appendix. In it, children are quoted as observing that "everyone in my whole world had gone to PChAD," and that "if PChAD is coming we run," evoking traumatic experiences of residential school attendees.

The authors of these reports arrived at the conclusion that children needed to be subject to longer-term trauma of confinement, despite providing no evidence to support the conclusion – or any evidence to support the program's existence at all.

American health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recently stated that the "therapeutic community" model favoured by the Alberta government will be adapted as forced labour camps for people who use drugs.

This may have precedent in western Canada: Marshall Smith, the former chief of staff to the Alberta Premier, has faced allegations of forced labour during his time running a therapeutic community in Prince George. Meanwhile, thousands of American children who use drugs are forced into the Troubled Teen industry's labour camps each year.

Meanwhile, opinion columnists like The Globe and Mail's Marcus Gee continue publishing fluff pieces on Marshall Smith while rashly endorsing forced abstinence legislation.

A fact that routinely goes unmentioned by these columnists is that expansion of forced abstinence is certain to have deadly outcomes. We do not know the survival rates of the 600 or more children ordered into PChAD each year. However, there is no shortage of horror stories investigated by the OCYA, including that of Gavin, an Inuit child forced through withdrawal via PChAD fourteen different times from age 14 to 17.

Among the twelve youth deaths compiled by the OCYA in 2018 was eighteen-year-old Zoe, daughter of Moms Stop the Harm's former Alberta director Angela Welz.

Welz and her son Max shared their experiences losing Zoe to a drug poisoning just four months after her second admission to PChAD — Welz pleading that "before any more support is given to PChAD, a review should be conducted of the act and its policies."

Although the Alberta government kept its review hidden, readers are encouraged to view it today alongside its AHS and ThreeHive counterparts.

This story was shared with Paid subscribers earlier on February 18 and is now publicly accessible.

Call for support: if you know professionals or academics who might be interested in supporting this work, they are likely eligible to claim the cost of a subscription as a professional development expense! Please share it.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis on topics concerning the war on drugs using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.