Overdose app falters as Alberta government accelerates war on supervised consumption

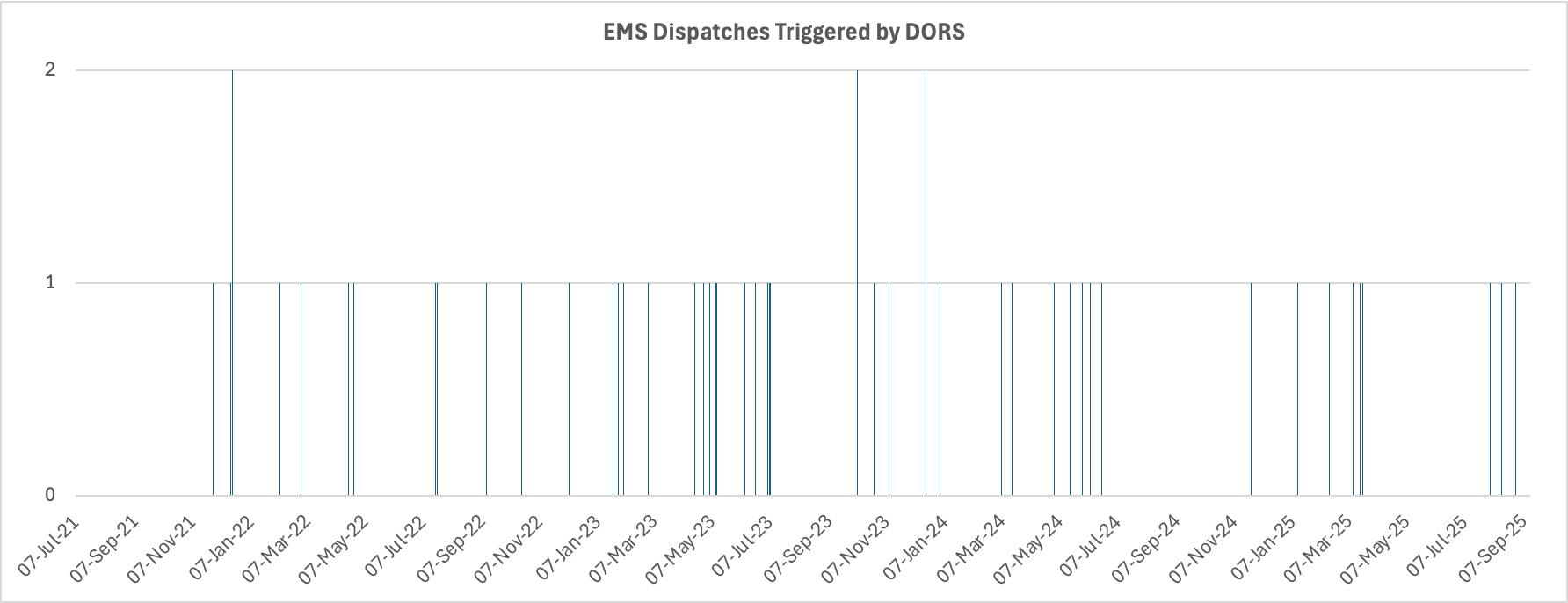

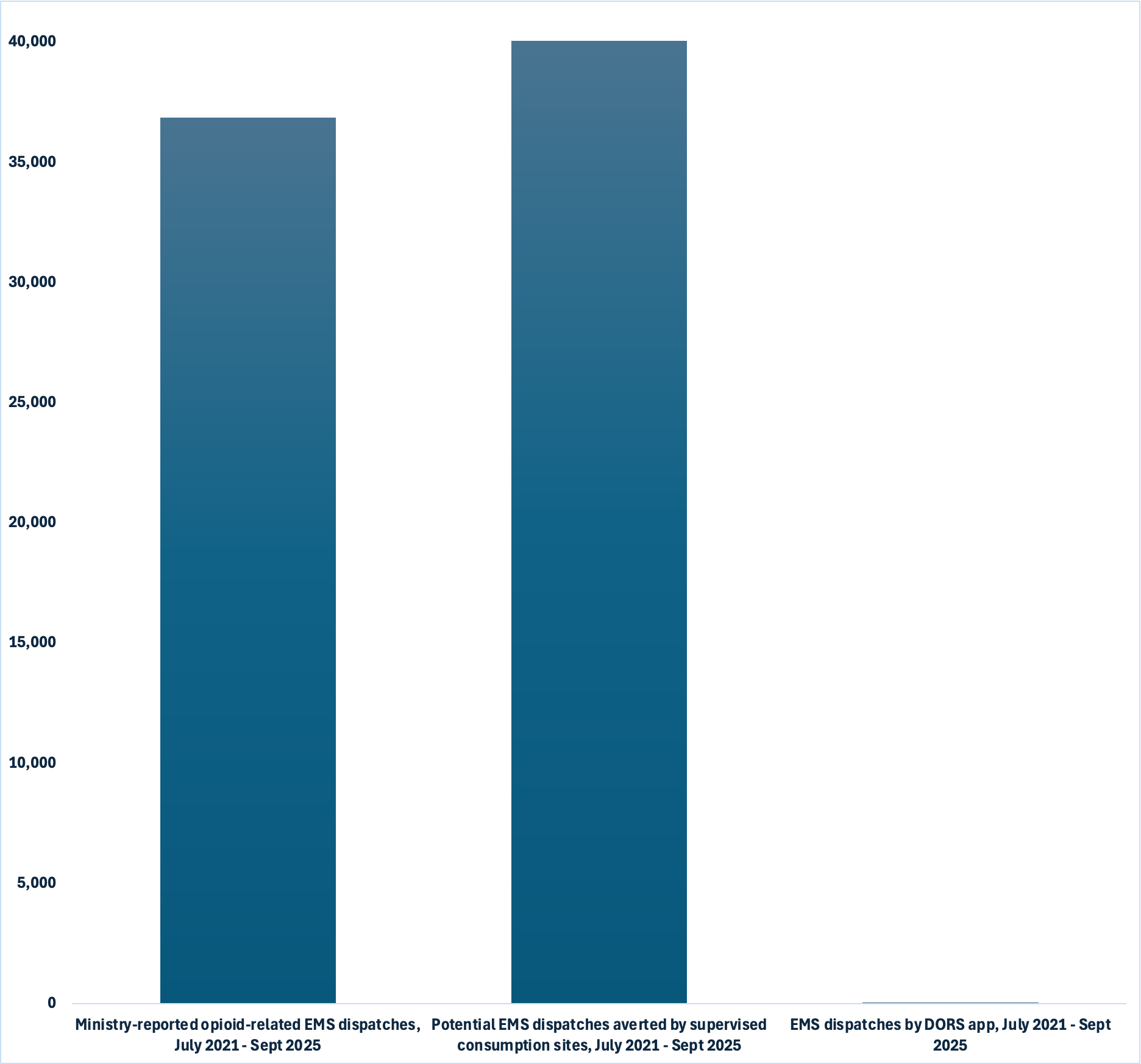

Launched to government fanfare on sole-source contracts, the Digital Overdose Response System app is barely used most days and has registered just 51 ambulance dispatches over four years –– around 0.14 percent of the ministry's under-reported dispatches for opioid toxicity in that period.

In July 2021, the Alberta government launched the Digital Overdose Response System (DORS) smartphone app to alert 911 if the app determined a person engaged in a session may have experienced a drug poisoning. The app was piloted in Calgary, then expanded to the rest of the province in June 2022.

For years, the Ministry refused to provide data on DORS use rates and overdose reversals. In June 2023, Global News reported that just eighteen app sessions resulting in EMS dispatch, an undisclosed fraction of which were genuine drug poisonings.

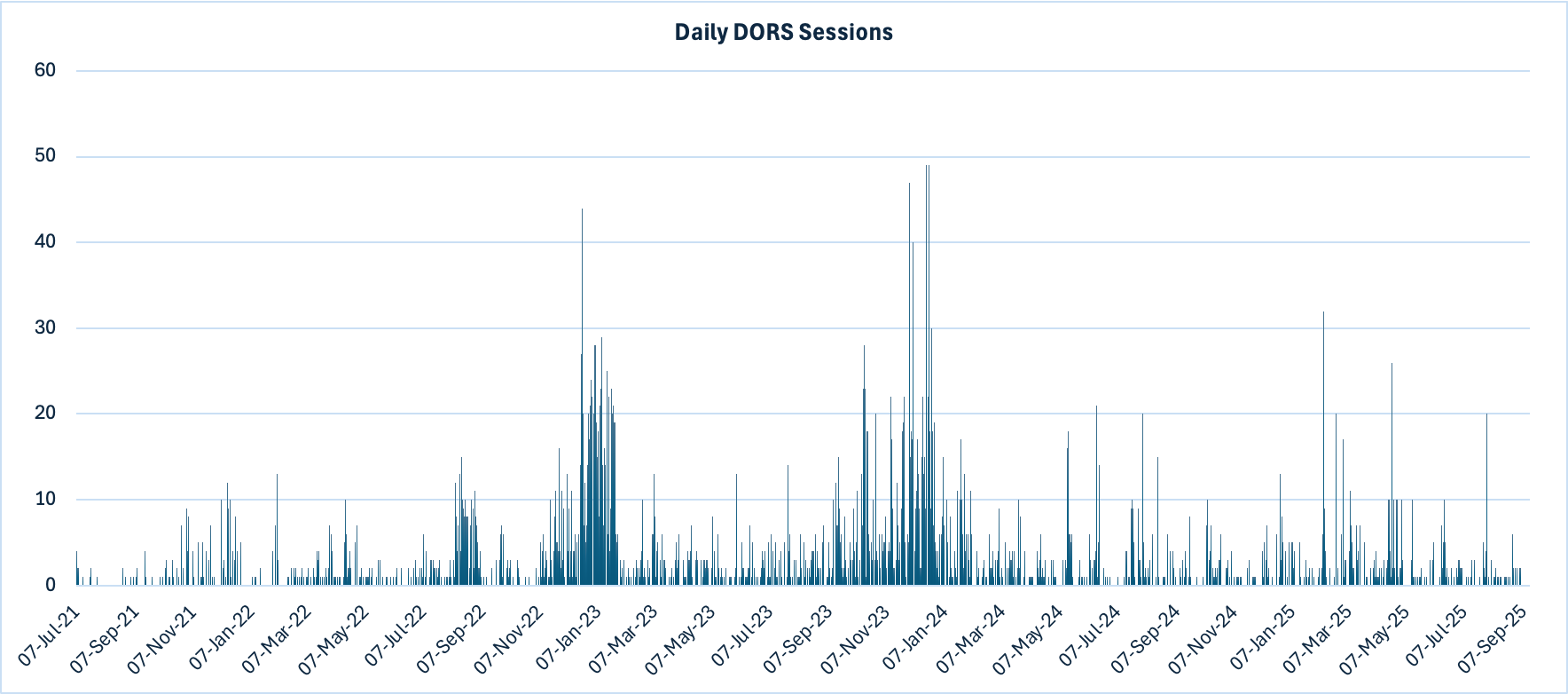

New documents obtained through freedom of information reveal that on most days since it launched, the app registered fewer than five user sessions. The app triggered EMS dispatch just fifty times in four years – 0.14 percent of the roughly 36,858 EMS dispatches for opioid-related events reported by the Alberta government during that period. (Separate documents obtained by Drug Data Decoded reveal the Alberta government has only been publicly reporting around a quarter of EMS dispatches for drug toxicity – story upcoming.)

In comparison, supervised consumption sites in Alberta have registered more than 40,000 adverse events, the vast majority of which required naloxone or oxygen administration, and in some cases, EMS dispatch.

The Alberta government has repeatedly stated that the DORS app was designed to address the high percentage of drug poisonings occurring in people's homes. However, on 81 percent of days in its four-year history, the DORS app was used fewer than five times. Use of the app appeared to spike around Christmas Day in 2022 and 2023, but not in 2024.

Overall, these data show that it is impossible for the app to have had any serious mitigating impact on population-level drug fatalities inside or outside people's homes since its launch.

In November, the Alberta government announced the imminent closure of the supervised consumption site at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton. The reasoning given by Minister of Mental Health and Addiction Rick Wilson was low use rate of the site. “There's only like one or two people max, new inpatients per day. So the use was pretty low," Wilson told CBC. In 2024, there were 1,212 drug consumption events at the site – 55 percent more than the total sessions recorded in DORS during the same year.

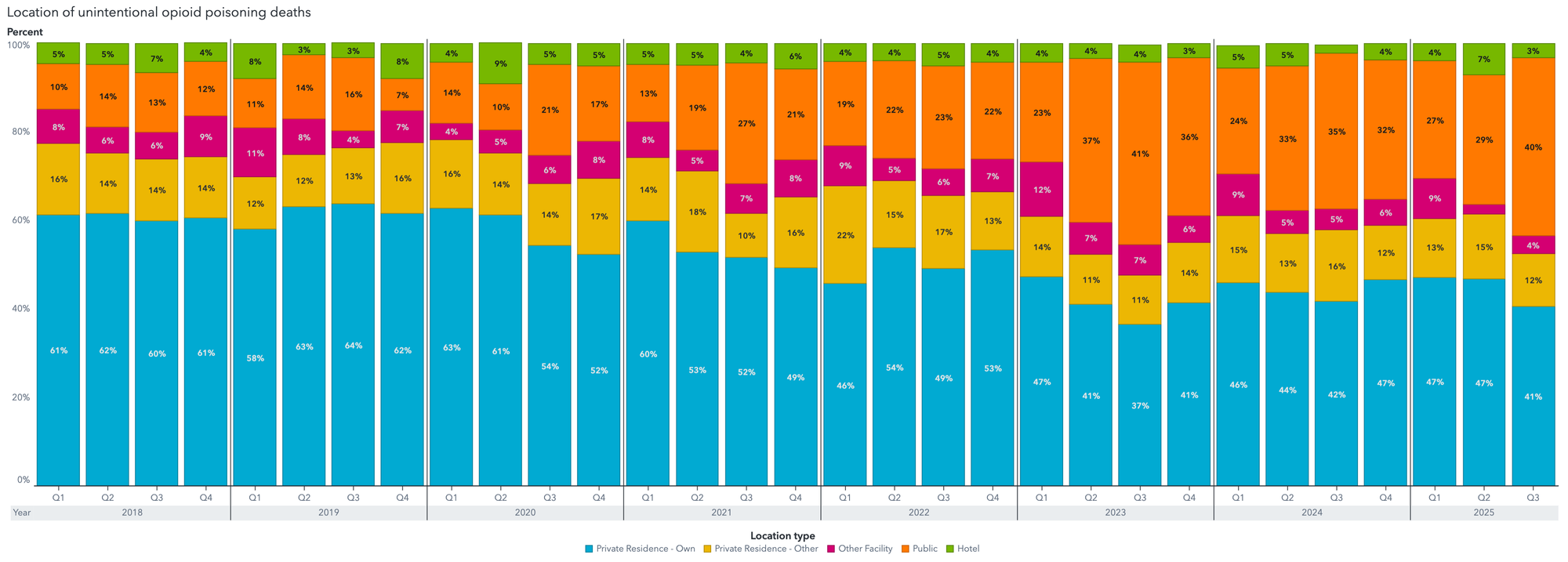

Around the time it was launching DORS in 2021, the provincial government buried a report showing the proportion of drug poisoning fatalities rapidly increasing among unhoused communities. The report remained hidden until February 2025. From 2021 to 2025, roughly one-third of opioid fatalities occurred in public spaces – a proxy indicator of deaths among unhoused people. A fraction of one percent of the total population is unhoused, meaning unhoused people are at hundreds-fold higher risk of overdose death than housed people.

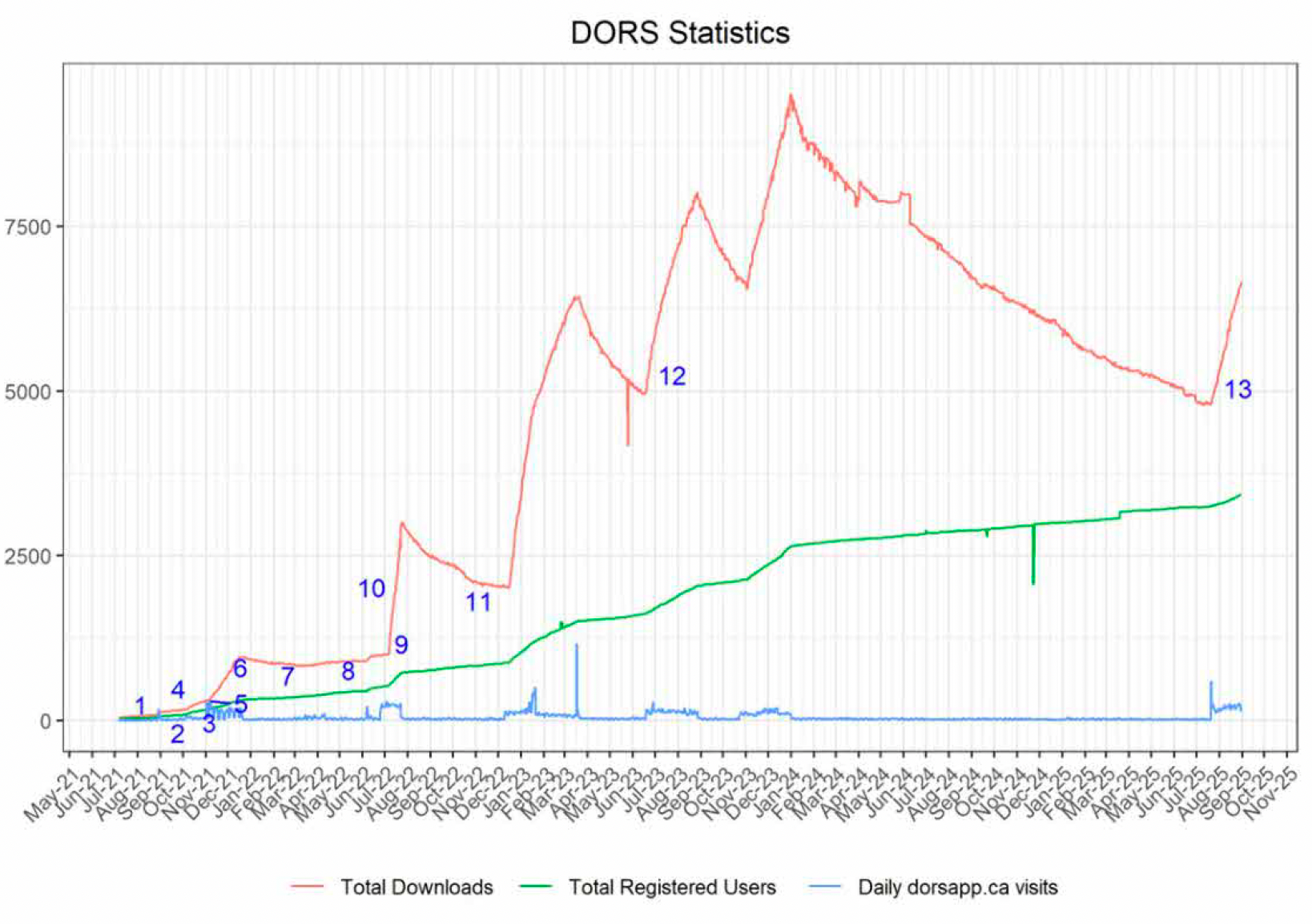

Instead of confronting the DORS app's minuscule impact on the drug toxicity crisis, the government has repeatedly pointed to its number of downloads and registered users as measures of success. These numbers are easier to distort than outcome data, such as app sessions per day and EMS dispatches. This parallels the government's broader aversion to demonstrating outcome data for its bed-based 'treatment' spaces, which have received hundreds of millions of infrastructure and operational dollars.

These new DORS app revelations come as the Alberta government intensifies its assault on supervised consumption services. The government closed the Red Deer site on March 31, which was followed by a new wave of overdoses in the city. This fall, the government also closed the site at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton, and is now threatening to close the sites in Calgary and Lethbridge. These closures would leave only the two remaining sites in Edmonton along with the site in Grande Prairie from the eight sites that existed in Alberta when the United Conservatives took power.

At their peak in 2019, supervised consumption sites had 1,307 daily visitors across the province. In the most recent quarter, the remaining sites had 426 daily visitors.

Aaron Brown was a regular visitor to the Red Deer overdose prevention site for years before the site's closure. In early 2025, he successfully obtained a court injunction delaying the government's closure of the site. The injunction was not extended by the provincial court on the basis that it could not conclude "that there is a real probability that Brown will suffer unavoidable irreparable harm if OPS closes," opening the door for the government to close the site.

In his affidavit, Brown had described the closure of the Red Deer site as a "death sentence." Validating his concern, Brown has been hospitalized twice for drug poisonings since the site's closure – one in April, soon after the site's closure, and the second last fall.

Without conducting a call for proposals, in 2021 the DORS contract was granted by the Alberta government to Aware360, a company that makes apps governing safety in the oilpatch and monitoring intoxication at work. This allocation took place months after a research partnership between Alberta Health Services and the University of Calgary was cancelled by the Alberta government just one day before its phone-based overdose response system was set to launch.

Sole-source contracts allocated to Aware360 for the app's development and implementation totalled $960,000, with at least $372,000 in operational contracts since then. The Alberta government also spent $3.3 million on advertising in 2022-23, in part to promote DORS, plus undisclosed amounts in other years.

A 2020 Calgary Sun column linked the government's pivot of DORS to a government-appointed panel led by Carson McPherson, who later co-founded ROSC Solutions Group.

In the mid-2010s, McPherson worked with Marshall Smith, former chief of staff to the Alberta premier, after Smith’s ill-fated stint leading Baldy Hughes therapeutic community. The year before Smith was hired into Alberta's Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction, McPherson and Smith again overlapped at the BC Centre on Substance Use (BCCSU), where they contributed to a document that closely matches the framework of the Alberta Recovery Model.

Recent reporting by Charles Rusnell links McPherson's company, ROSC Solutions Group, to the so-called CorruptCare scandal in Alberta health care procurement through a "tangled web of connections between the UCP government, RSG, [medical supply company owner Sam] Mraiche and the Métis Nation of Alberta." Mraiche's business dealings were detailed at length by The Globe and Mail last month.

The app's technical shortcomings were uncovered by journalist Alanna Smith five months after its launch. In her story, an app developer described DORS as "poorly constructed" with weak location pinpointing capacity, installation glitches, and a poor user interface.

The government's strategic direction set between 2019 and 2020 was characterized by increased surveillance measures and greater coercive powers over vulnerable people paired with eroding harm-reduction capacity. This has been shored up by the country's worst government transparency, dismantling of informed consent, nefarious data manipulation, untold billions in corrupt contract allocations, and multiple allegations of journalist and whistleblower intimidation.

While thousands perished in Alberta to an unregulated drug supply, the Digital Overdose Response System was pushed by a government eager to show it was doing something about a crisis it appeared to have little intention of solving through policy. The evidence that DORS had any population-scale impact on the crisis is nonexistent. Meanwhile, the government vilified supervised consumption for "crime and disorder," contrary to evidence that now links declining crime rates to supervised consumption sites.

In its freedom of information response to Drug Data Decoded, Alberta's Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction provided a graph showing the total downloads (including both iOS and Android), the total registered users, and the daily visits to the DORS website.

Drug Data Decoded approached Gordon Casey, who co-designed the Brave Overdose Detection app, to understand the periodic declines in download numbers observed since the app's launch. Casey explained that the number of downloads is a largely meaningless metric because of the differences in how downloads are counted and retained over time between Apple and Android, as well as interference from app updates. He suspects that some of the large spikes in user sessions are related to app trainings and product demonstrations.

"It's probably more interesting to see what number of metric 'X' results in a certain threshold of escalations or dispatches," Casey said. "Then you'd know what to drive for, whatever it actually means." The graph provided by the ministry does not show the daily sessions or EMS dispatches, which are the key outcome metrics.

In contrast to DORS, Casey’s Brave app was designed with guidance from dozens of people who use drugs, settling on a model that maintained full anonymity of users. However, owing to lack of uptake by governments, who appear eager to gather user data through other apps such as My Recovery Plan, Brave ended its overdose app last year. The Alberta government revealed at a November committee meeting that personal data of 7,480 people was collected by My Recovery Plan.

With the ongoing implementation of the Compassionate Intervention Act, which legislates the detainment, substance use withdrawal, and forced medication of people who use drugs in Alberta, concerns around data privacy could evolve into real-world consequences for app users.

The obtained documents show DORS has collected the personal data of 3,427 registered users, an unknown number of which are people who use drugs (versus ministry staffers, training recipients, or other non-app users). The app’s privacy impact assessment, which was mostly redacted in the ministry's freedom of information response, explains that data collection is “limited only to that information required to contact the user to determine if they need assistance, and to dispatch emergency services if required. No health information (e.g. name, gender, Personal Health Number) is collected.”

This indicates that personal information including address, phone number, and perhaps IP address are being collected – enough to triangulate a person’s identity. The DORS privacy policy also tells app users that their data can be shared to “provide personalized experiences and offers about relevant products and services, “to comply with any applicable law or regulation, to respond to a governmental request, to detect, prevent or aggress fraud or other security concerns,” and “to protect against personal or property harm.”

While it is conceivable that DORS user data could be turned over to the government through a court order under the Compassionate Intervention Act, no evidence indicates this has yet occurred. The ministry provided 'no responsive records' to a request for instances of government requesting personal data from DORS.

The ministry's response to the freedom of information request was made as a PDF, which cannot be used for data analysis. When asked for the original spreadsheet of the data, the ministry refused:

The Act does not require the public body to provide records in a specific format chosen by the applicant. The duty to assist does not extend to re‑creating, restructuring, or re‑formatting records into a preferred format when that is not how the public body normally discloses information.

Unfortunately, we are only able to provide you with access to the responsive information in the format in which it is processed and approved for release, that is, as a PDF. This fulfills our duty to assist and our obligation to provide access to the records that exist, while ensuring compliance with the Act and with secure disclosure procedures.

In place of the ministry’s refusal, Drug Data Decoded converted the DORS usage data into a spreadsheet that is shared below and available for public and media use. (Note: formatting of the "Daily Average Session Length" column could not be adjusted, rendering those data unreliable for graphing.)

An early version of this story was shared with Paid subscribers on January 9, 2025.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.

This content is not available for AI training. All rights reserved.