Ophelia Black v. the UCP

Irony in the court!

The Overdose Prevention Site of King’s Bench

The hearing opened up with lawyer Avnish Nanda making a rather unusual request: for Ophelia Black to inject her hydromorphone dose onsite at 11am sharp.

Justice Feasby — did I see a glimmer of appreciation in his eye? — granted the request with instruction that the neighbouring board room be left “spic-and-span”.

Spic-and-span! Have you seen Ophelia inject drugs before, Justice?

I guess not, but still — Ophelia has better aseptic technique than most microbiologists I know. She once called me to ask if she needed to re-autoclave all of her gear after she spotted a single fruit fly in her room.

But before we get into the muck, a moment of appreciation: a court hearing to determine someone’s right to inject an opioid, interrupted to secure space in the courthouse for the complainant to inject an opioid.

Dr. Nathaniel Day, expert

At the start of February, Dr. Nathaniel Day was promoted from official UCP Ribbon-Cutter & Medical Director of the Virtual Opioid Dependency Program (VODP) to Medical Director of all AHS Addiction & Mental Health Services.

Strangely, at that moment, the grace period in which Ophelia could be forced off her take-home prescription and into the downtown Calgary clinic three times a day was cut short by a full month. This triggered a February 7 emergency hearing on Ophelia’s case that forced the UCP Minister of Mental Health & Addiction, Nicholas Milliken, to write a letter reaffirming the cutoff at March 4.

During the March 1 hearing, Nanda argued that the UCP Government lawyer narrowed the scope of Dr. Day’s cross-examination on the grounds that he was not providing testimony as an expert on opioid prescribing, but rather as an expert on the services offered by AHS.

Let me say that again, in bold font: the physician in charge of Alberta’s Opioid Dependency Program, who now governs all opioid prescribing in the province, was partially shielded from cross-examination on the basis that he was not put forth as an expert on opioid prescribing.

The good doctor also said this in his cross-examination, which fits perfectly alongside my last post investigating the UCP’s overtures to forced abstinence:

He even went on to say this, which really fits with the UCP’s entire approach to drug policy: since they don’t like drugs, nobody else should either.

Note: affidavits and other testimony will be made public at some point, but for now must remain private to protect sensitive information. I obtained them through consent of the complainant, Ophelia Black.

Dr. Sharon Koivu, expert

Another angle of attack used by Nanda to dismantle the UCP Government’s case was an attempt to have Dr. Sharon Koivu’s affidavit struck from the record owing to some problematic testimony that arose.

Dr. Koivu lives in London, Ontario, within a kilometre of the London Intercommunity Health Centre (LIHC) which opened its Safer Opioid Supply program in 2016 that scaled up with federal funding in 2020. Part of Dr. Koivu’s testimony attempted to transplant her anecdotal experience with property crime into a broader argument against safe supply: essentially, since she knew someone who had a bike stolen, the program must be at fault.

First, crime is not the least bit relevant to Ophelia’s case. Ophelia is one person quietly using drugs deep in a suburban enclave, obtaining utterly decentralized daily prescriptions from a nearby drug store. That didn’t stop Dr. Koivu from applying the common drug war propaganda method of stigmatizing harm reduction services wherever they pop up by connecting them to crime, disease or disarray.

As someone told me outside the hearing, Ophelia’s “not taking her evening shot, donning a Catwoman suit and hitting the streets to steal bikes from her neighbours.” Which brings up the point that we could eliminate subsistence crime by helping people off subsistence lifestyles. In other words: ensure everyone’s basic needs are met, including medicines.

Wait so they tried cutting off her take-home script and mandating she go to a central clinic and then brought in Dr Sharon Koivu to provide “evidence” that centralized clinics increase crime and thus she should go… to a clinic?

— Juls Budău (@JulsBudau) 6:21 AM ∙ Mar 3, 2023

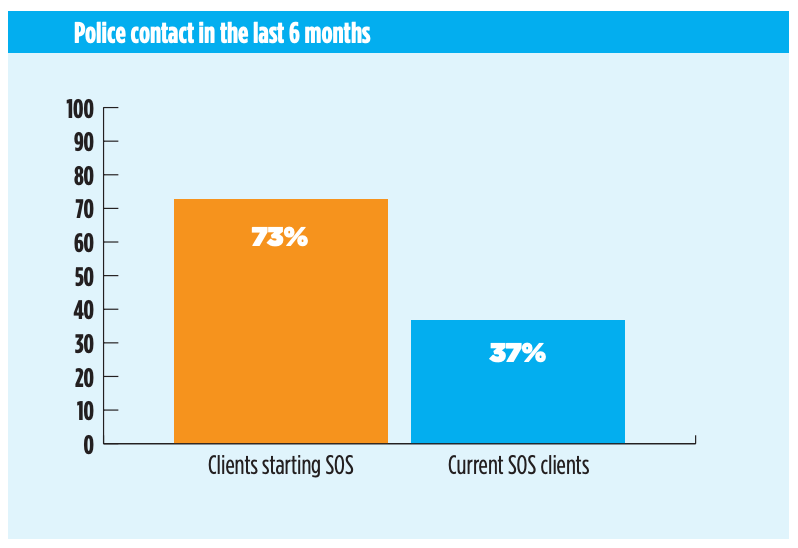

Second, it’s very odd that Dr. Koivu wouldn’t have instead focused on the remarkable statistics published by the LIHC Safer Opioid Supply program evaluation team.

For example, only 37% of active SOS program participants reported having contact with police over a 6-month evaluation period, versus 73% of incoming participants.

Another figure shows a massive reduction in criminal activity to obtain drugs among active participants. There are many more such figures from the preliminary evaluation published in January 2022, with peer-reviewed studies now being published (the first, on clinical outcomes, was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal).

Ophelia Black, non-expert

Finally, a key UCP angle was to present Ophelia as being ready for the Narcotics Transition Services program — to have her take-home prescription cut off and to begin appearing daily at the central clinic for her transition to abstinence.

To achieve this, they used a medical record from February 23 in which Ophelia’s prescriber described her as “coherent” and “thinking linearly”. The UCP’s lawyer then argued that since Ophelia was so put together, she was clearly no longer in need of her prescription.

It’s hard to convey the sick irony of this argument without having been in Ophelia’s shoes, but the gist of it is she is being pulled off a medicine that is working for her on the basis that it is working. It also creates a highly stigmatizing visual of people who use opioids, which of course is the entire mandate of the Ministry of Mental Health & Addictions, so no surprise there.

Related, the UCP lawyer at one point actually stated that Ophelia is not an expert, in an effort to discredit her testimony in favour of listening only to the doctors. I have a lot to say about this, but I’ll leave it here: if you’re a health care provider offering a legal affidavit in a case involving someone who uses drugs, you had better provide testimony reinforcing the individual’s expertise on their own health.

At this point in the crisis, failing to do so should be grounds to dismiss your testimony.

Anyway, like I said: ironies. Hope you enjoyed that, Mr. & Ms. Smith ;)