Edmonton set opioid poisoning records while Province quietly hid medical examiner review

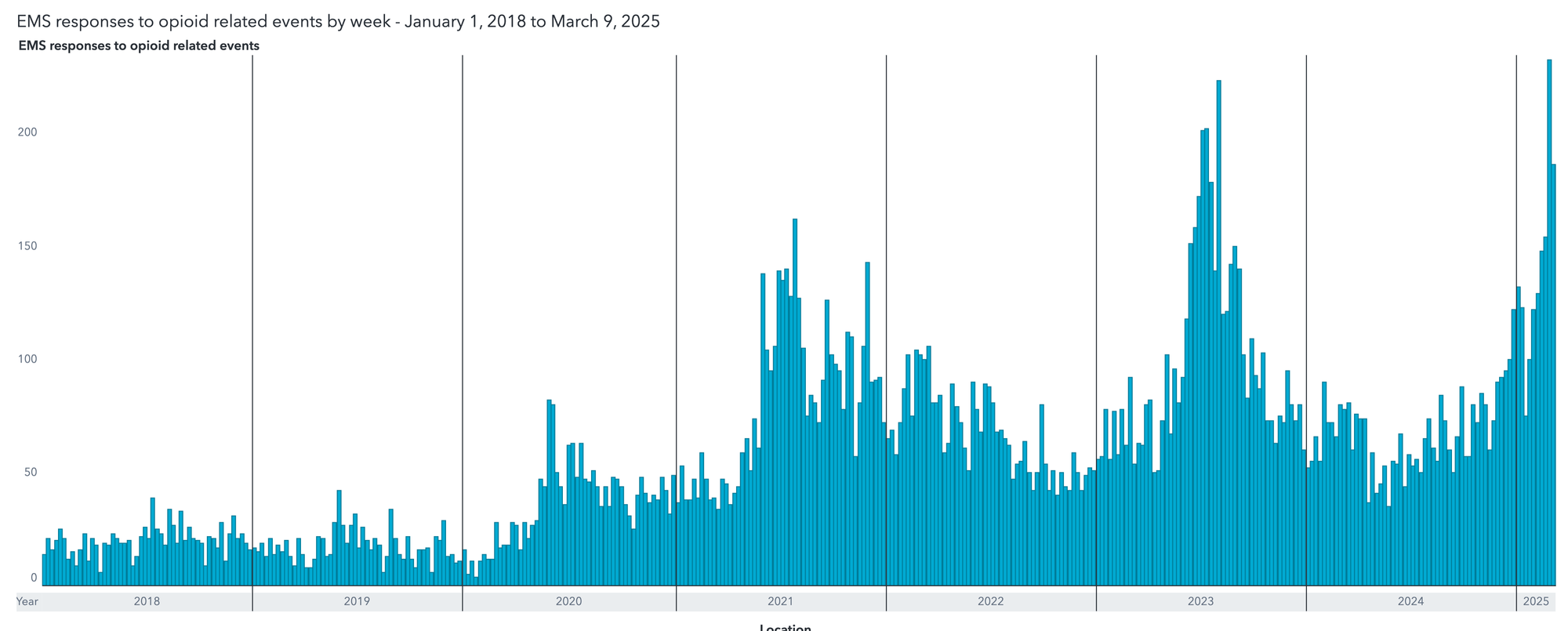

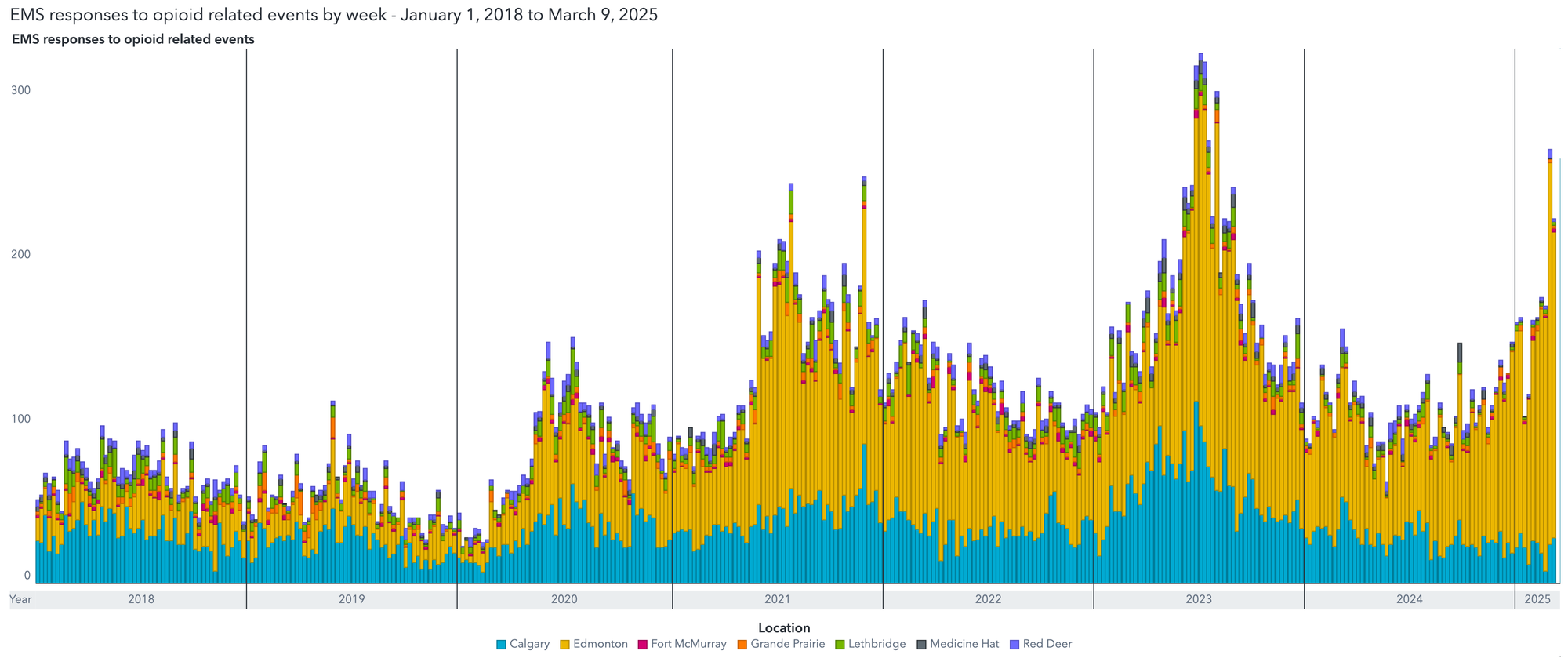

Edmonton EMS dispatches for opioid poisoning have hit their highest weekly count ever. While other provincial governments issue warnings, Alberta has been hiding a key mortality report that could have informed solutions on the ground.

Edmonton is setting new records for EMS dispatches to drug poisoning emergencies – a pattern that has tracked closely with fatalities for many years.

And while health authorities from Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia issue warnings about the unusual toxicity of the current unregulated drug market, the Alberta government is choosing silence.

Previous spikes in drug poisoning EMS dispatches have correlated tightly with drug poisoning mortalities, suggesting a high likelihood that coming months will show a sharp uptick in both Edmonton and provincial drug mortalities beginning in January 2025.

This is the first instance on record where EMS dispatches for drug poisonings have decoupled between municipalities – previously, EMS dispatches followed similar patterns among Alberta municipalities. Edmonton has never shown greater than 3-fold-higher dispatches than Calgary, but the current disparity is nearly 20-fold.

This coincides with outgoing Edmonton Police Chief Dale McFee assuming a new role as Alberta's most powerful unelected official, and his Alberta government is holding its silence about the emergency.

Approached for comment, Angie Staines of 4B Harm Reduction described to Drug Data Decoded the current situation in Edmonton:

There is an air of desperation for community and front line and it feels so very dark. Community tells us all the time they feel scared and that they have just been forgotten and don’t matter. It feels like we are trying to fix a breaking dam with a piece of gum.

During his tenure as Chief of Police, McFee launched the most aggressive campaign to dismantle encampments ever seen in Edmonton. Research has shown that decampments are followed by heightened drug poisoning risk.

Decampment action by Edmonton Police has been driven in part by commercial development near the Boyle-McCauley neighbourhood, home to Edmonton's highest density of unhoused and precariously housed people.

The campaign led by McFee overlapped with the dismantling of harm reduction services by the Alberta government and Edmonton's city administration.

In 2020, the most recent year for which such data are available, unhoused or unstably housed people comprised between 16 and 39 per cent of all unintentional opioid poisoning deaths, with the uncertainty owing to an uptick from one per cent in 2017 to 23 per cent of people who died of drug poisoning in 2020 with undetermined housing status.

These data were released as part of the government's "Review of Medical Examiner Data: Substance Toxicity Deaths in Alberta in 2020," which the government was forced to release following a freedom of information request submitted on November 6, 2024 by Drug Data Decoded.

The report was likely compiled in 2021, but the Alberta government used every tool at its disposal to delay releasing the document.

Despite internal documents revealing that the Ministry of Health located the 48-page document by November 8, its January 6 FOIP response insisted that "Alberta Health conducted a thorough search for records and found no responsive records related to the subject matter." The Ministry then suggested that the records might be held by the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction and offered to transfer the request to that ministry.

Deputy Minister of Mental Health and Addiction Evan Romanow told the Ministry's Privacy department on December 3 that "the Ministry of MHA will work to publicly release the report so this should not be disclosed under FOIP." This was two days before the initial FOIP deadline and a month before the Ministry of Health stated it held "no responsive records," despite clearly holding the records.

On December 4, internal correspondence showed that the Ministries would be "working...to update and finalize the report. It will then be released publicly online similar to the 2017 report." Two hundred and fifty pages of internal correspondence obtained through a follow-up freedom of information request appears to include the initial version of the Review, but the Ministry refused to disclose that version along with 100 other pages of documents under Section 24(1)(b) of the FOIP Act (consultations or deliberations).

The Review was not posted publicly until the end of February 2025, and no announcement was made by the Ministry when it was posted. As a comparison, the 2017 Review was released publicly in 2018. The release of the 2020 Review required more than 200 emails involving dozens of officials at two ministries, following the November 6 freedom of information request.

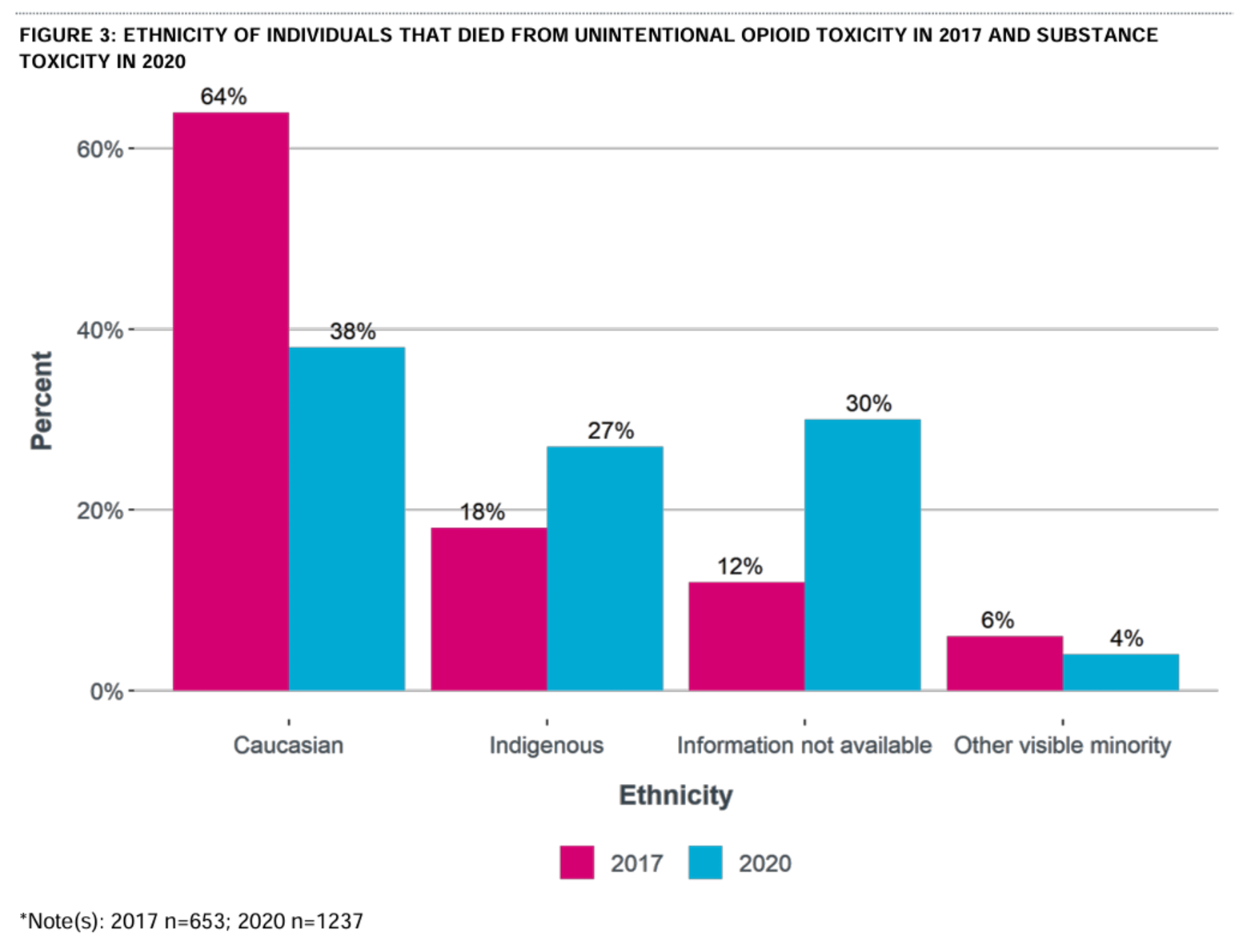

The Medical Examiner's 2020 Review reveals a sharp increase from 2017 in the proportion of Indigenous people dying from unintentional opioid toxicity, coinciding with a decrease from 64 per cent in 2017 to 38 per cent in 2020 in the proportion of deaths among white people in Alberta. Nearly one-third of the deaths in 2020 were people of undetermined ethnicity.

Drug toxicity deaths among people involved with Child and Family Services nearly doubled between 2017 and 2020.

The Review also revealed that only 35 per cent of people dying from unintentional drug toxicity were diagnosed with opioid use disorder, despite fentanyl being found in 85 per cent of deaths. People with any type of substance use disorder made up 78 per cent of deaths.

Just 8 per cent of deaths showed evidence of diverted prescription medications on scene. Hydromorphone, an opioid frequently dispensed for chronic pain that is also dispensed through safer supply programs, was detected in 2 per cent of deaths.

The report further reinforced the prevalence of drug poisoning mortality specifically among workers in the trades, transportation and equipment operation. Among people whose last known occupation was known at the time of death, these sectors made up more than half of deaths.

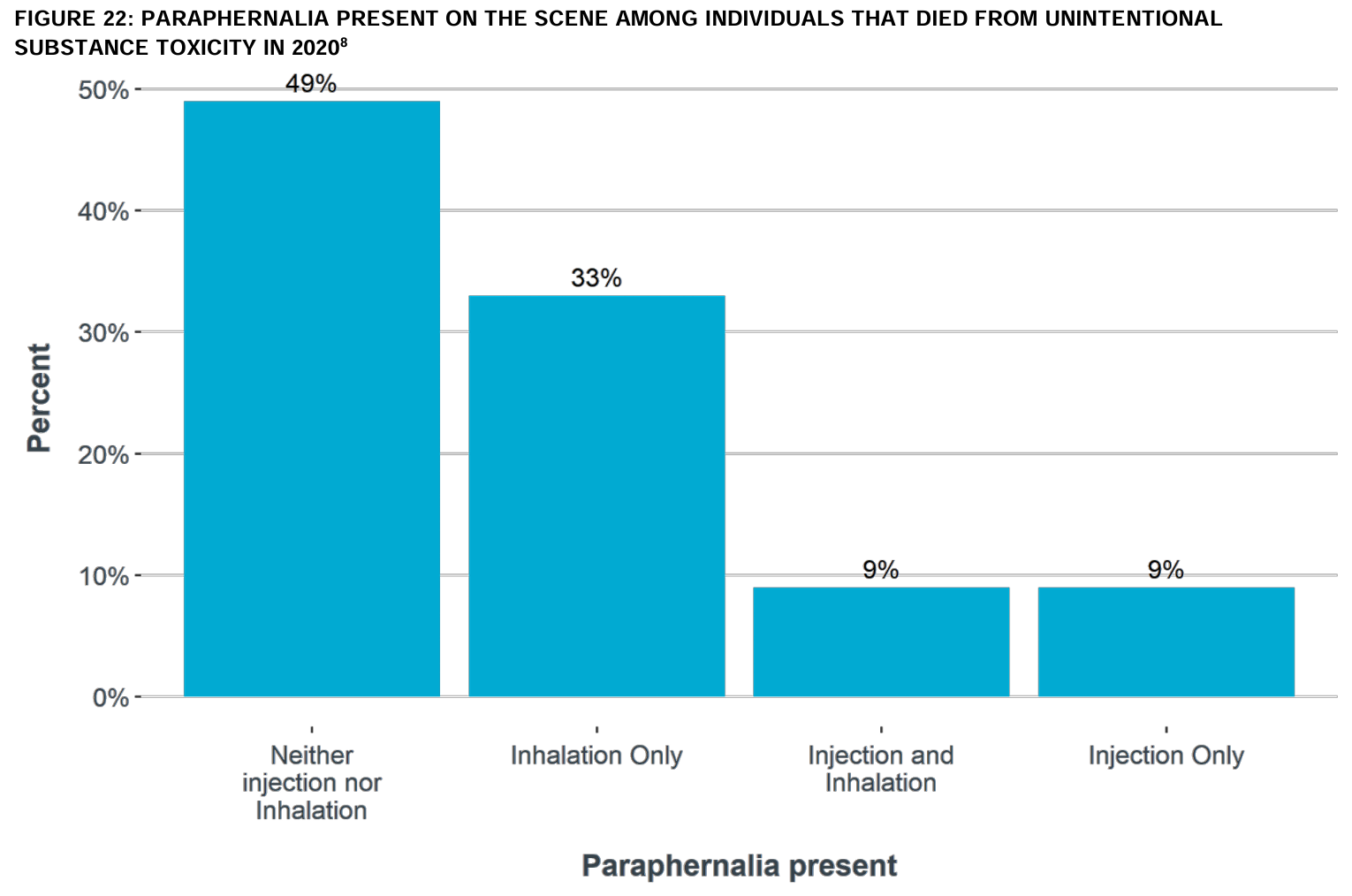

The government was also internally aware from the 2020 Review that inhalation equipment alone was being found 3.5-fold more frequently on the scene of drug deaths than injection equipment alone, suggesting that people were dying far more frequently following inhalation drug use. The Alberta government closed the province's only supervised inhalation site in 2020, in Lethbridge.

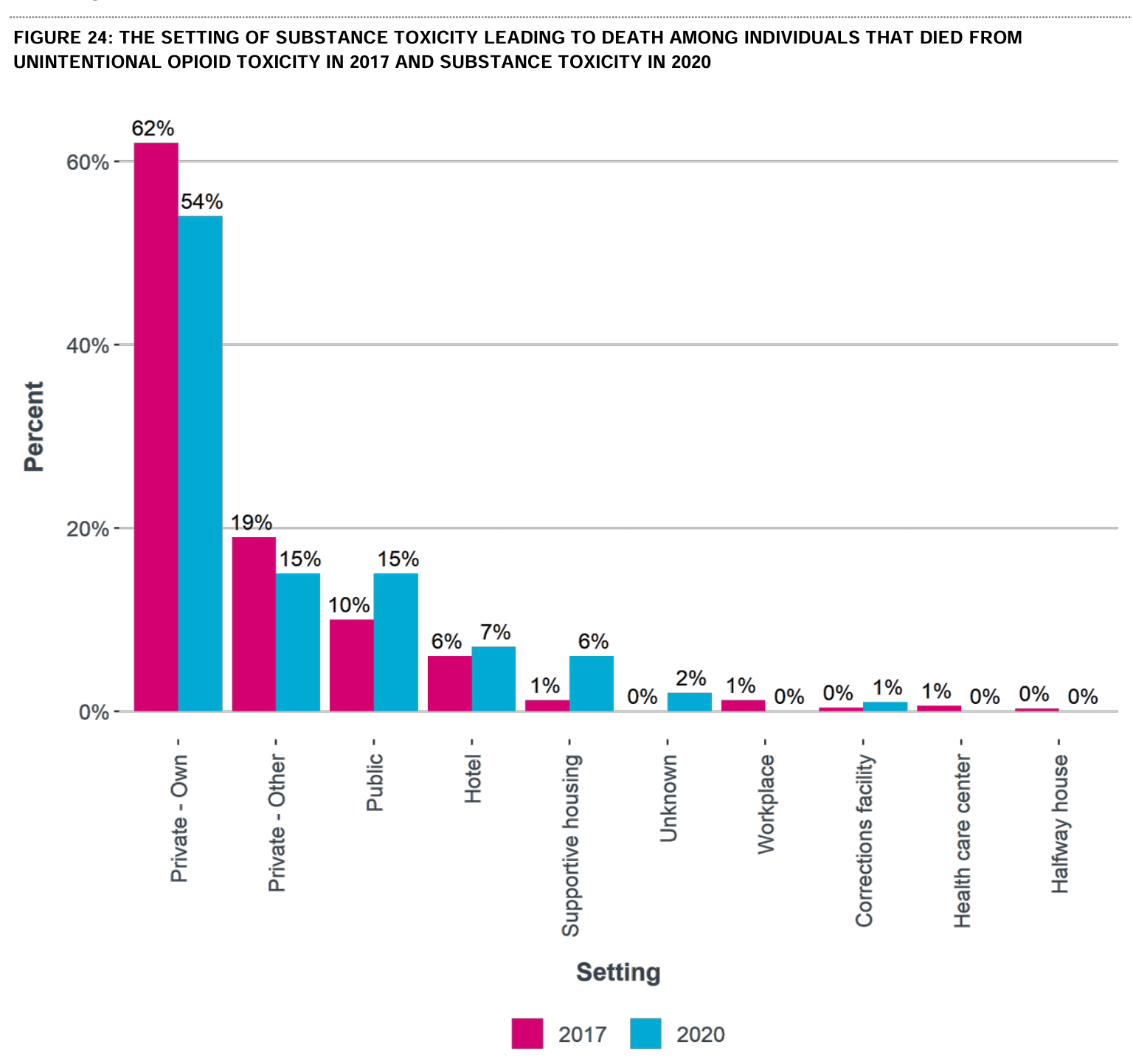

Deaths in public and in supportive housing saw large upticks, while deaths in private residence decreased from 2017 to 2020. Despite this, the Alberta government persisted with planned and actual closures of additional supervised consumptions, including at Edmonton's Boyle Street Community Services, that would mitigate these trends where they were occurring.

A naloxone kit was only found on scene in 15 per cent of mortalities in 2020, and in only two-thirds of these cases was naloxone administration even attempted. Reasons for a bystander not attempting administration included not being able to find the kit, not knowing where to inject the antidote, and deciding it was too late to attempt resuscitation.

The 2020 Review helps clarify several mortality patterns on which Alberta government policy had direct bearing: Edmonton's large unhoused population, which is over half-Indigenous, tends to prefer inhalation drug consumption –people who would have accessed supervised inhalation sites if they were available. They should also be granted full clemency from decampment operations—at minimum through the winter months and while drug supplies are at highest risk.

The city's large population of tradespeople, transport workers and equipment operators could have benefited from alerts, drug checking and supply regulation. The largely Indigenous population of youths dying in provincial care are similarly being neglected in favour of residential "treatment" and forced withdrawal measures.

After all, the government's own data show that 65 per cent of people dying from fentanyl poisoning do not have opioid use disorder.

Moreover, the government's decision to bury the 2020 Medical Examiner Review for four years should be deeply concerning to the public as the net continues to widen across the government on allegations concerning questionable dealings at the Ministry of Health. The public deserves to know who is benefiting from the privatization schemes being hatched in every provincial ministry.

Angie Staines had some more personal observations she was willing to share about what the government is allowing to unfold in Edmonton:

People are wired to the benzos, and to be honest that grind is incredibly hard – as if time doesn’t exist. It’s dystopian and surreal. Every single day I think about how thankful I am that [Angie's formerly unhoused son] Brandon isn’t out there stuck in that grind, but I also see the sadness and pain on his face during outreach when he runs into his friends and he sees people who have saved his life, been there for him, and sat with him in some of the worst days of his life. The suffering and trauma is some of the most unimaginable that I’ve ever witnessed. To be honest, it’s really hard to put into words or wrap my head around the fact we as a society are OK with letting people remain in that grind.

Note: Bag-valve-mask ventilators are critical additions to any drug poisoning kit. Make sure you get trained and carry a BVM if you're likely to encounter drug poisonings. BVMs can be obtained through formal training, at medical supply shops or agencies supplying harm-reduction equipment. Detailed instructions for conducting a BVM resuscitation are available here. Outreach groups are struggling to keep these stocked at $30 each, so please consider donating if you can to 4B Harm Reduction (Edmonton), Street Cats (Calgary), Prairie Harm Reduction (Saskatoon) or any local organization–they are all in need.

If your organization wants to be listed among these donation requests, please reach out at info@drugdatadecoded.ca.

If you have additional information on this story, please get in touch at info@drugdatadecoded.ca, where media can also request FOI documents related to this story.

This story was shared with Paid subscribers early on March 13 and made publicly accessible later that day.

Call for support: if you know professionals or academics who might be interested in supporting this work, they are likely eligible to claim the cost of a subscription as a professional development expense! Please share it.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.