Alberta drug policy is executing unhoused people

Across the province, risk of death from unregulated drug poisoning among people experiencing houselessness is skyrocketing.

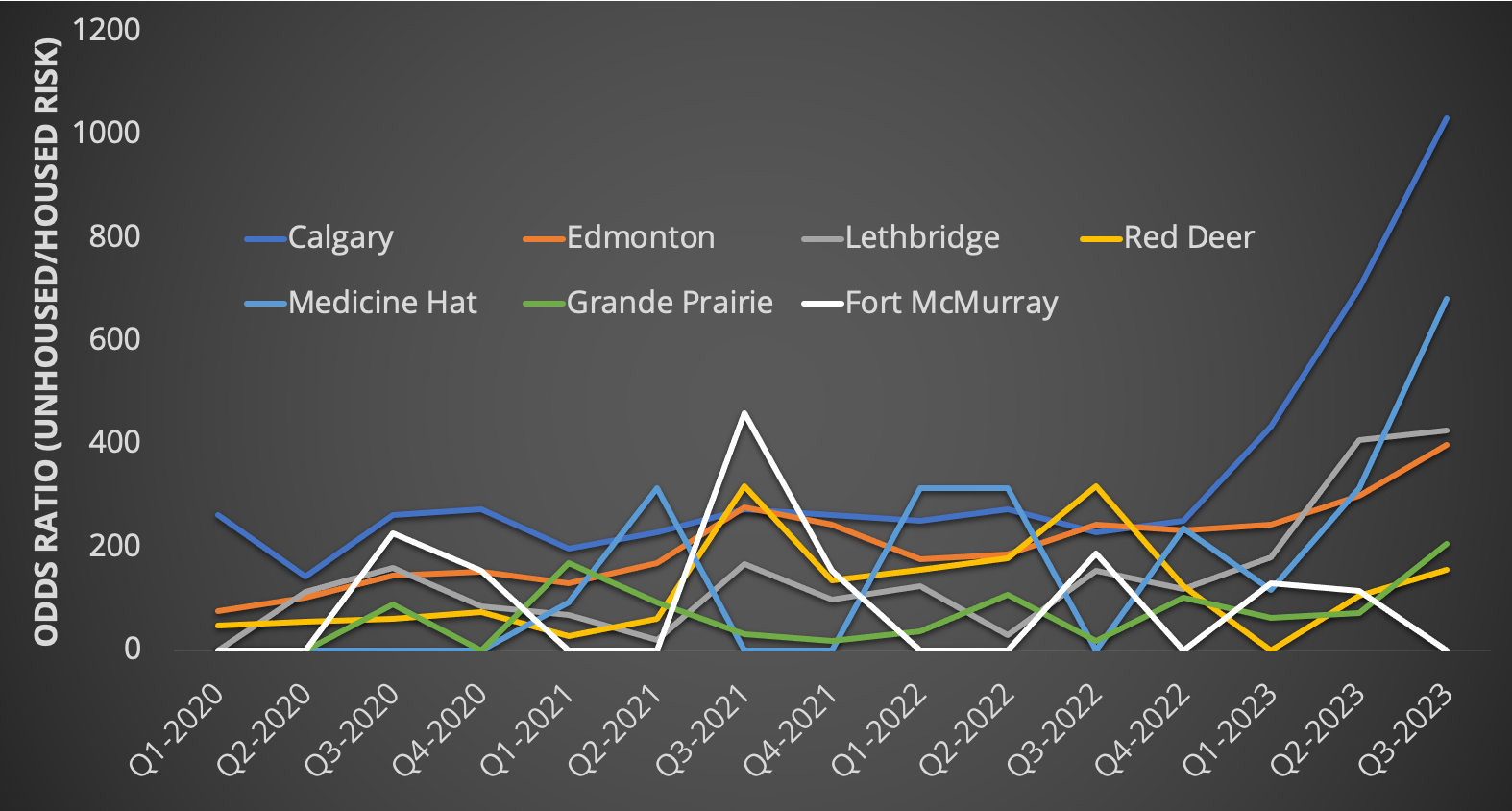

Across Alberta, people experiencing houselessness are now hundreds of times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people.

Leading the province in this grim statistic is Calgary, where unhoused people are now over 1000-times more likely to die of drug poisoning. In Lethbridge, Edmonton and Medicine Hat, the difference in risk is over 400-fold.

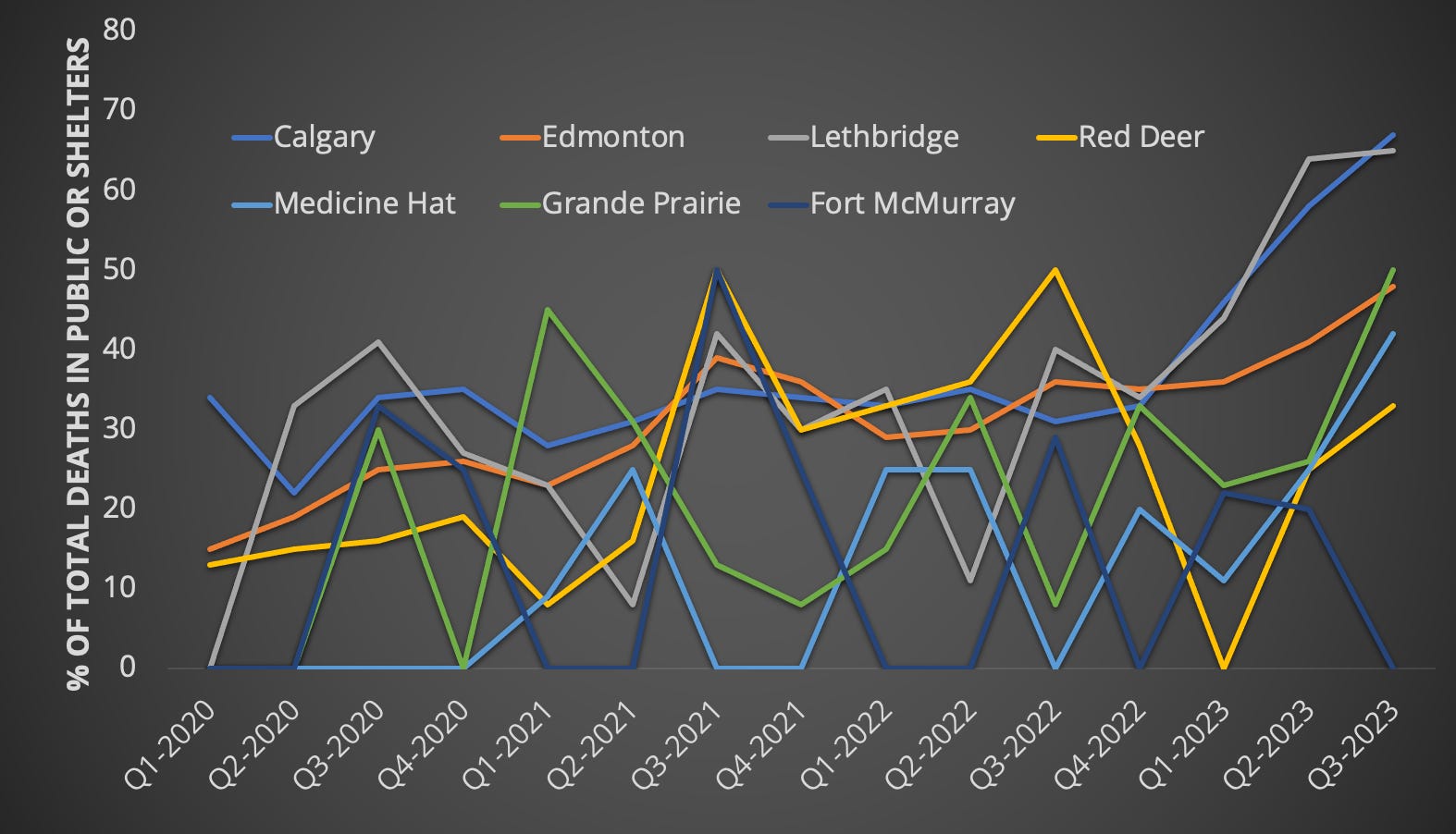

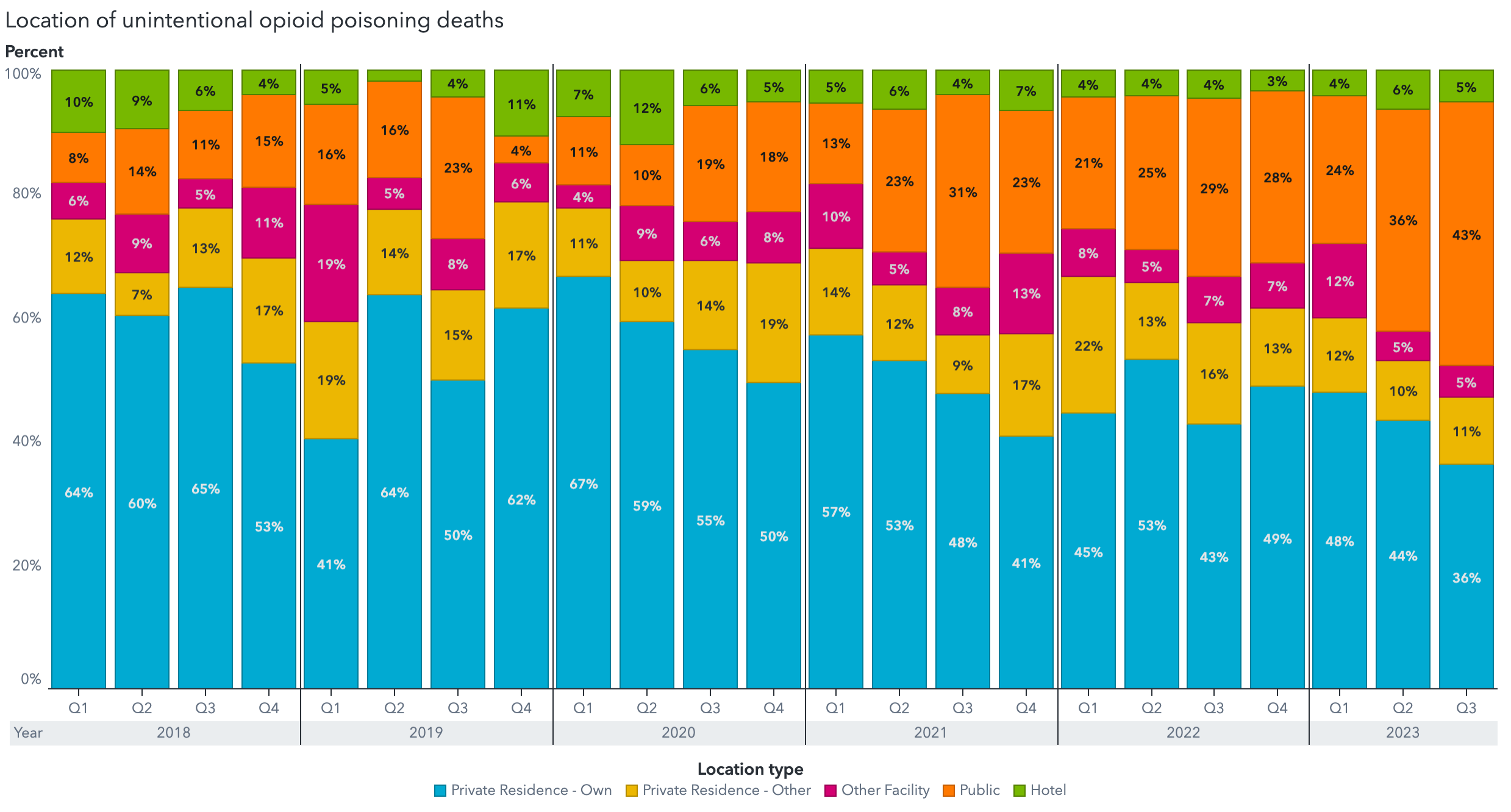

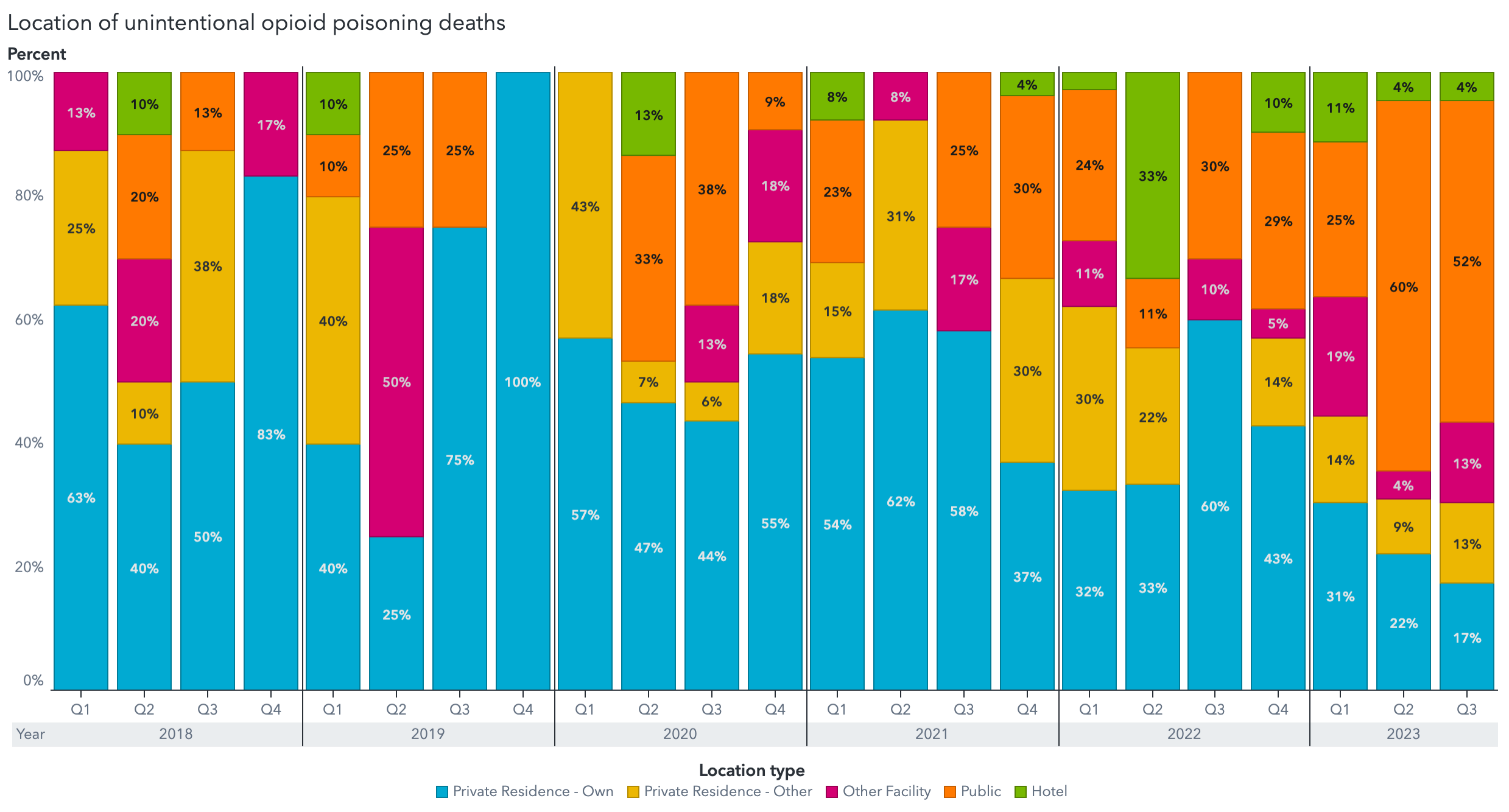

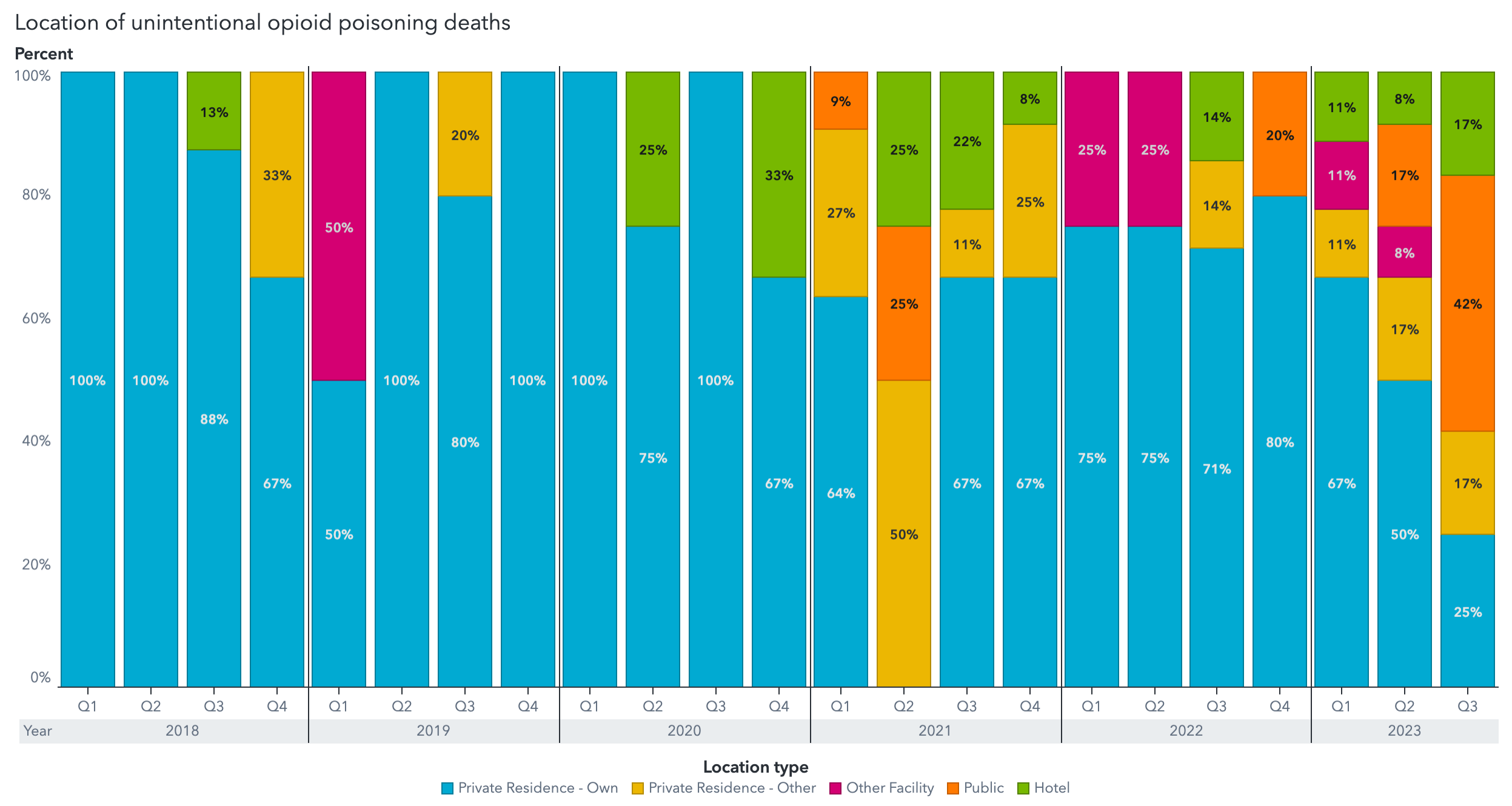

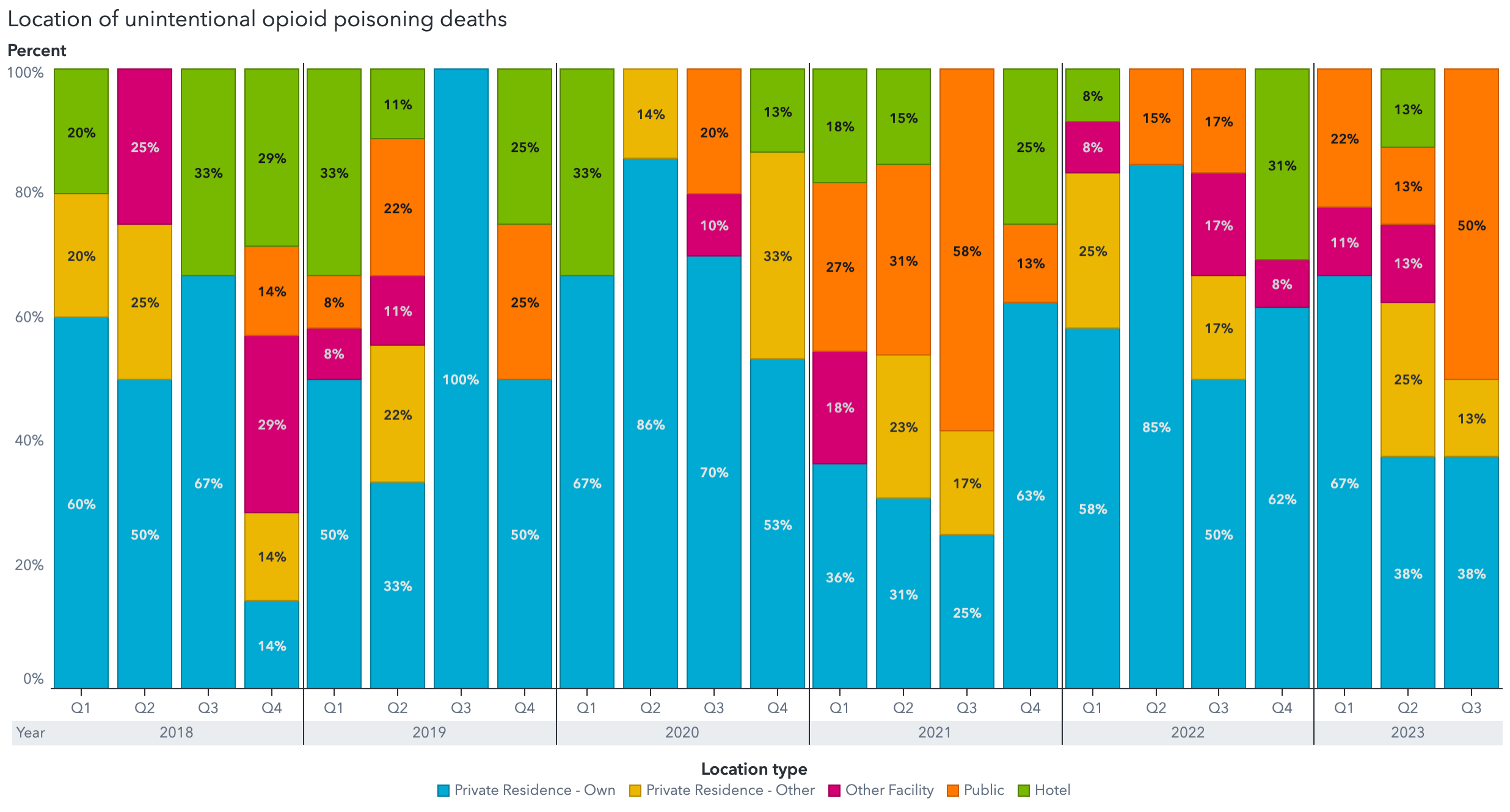

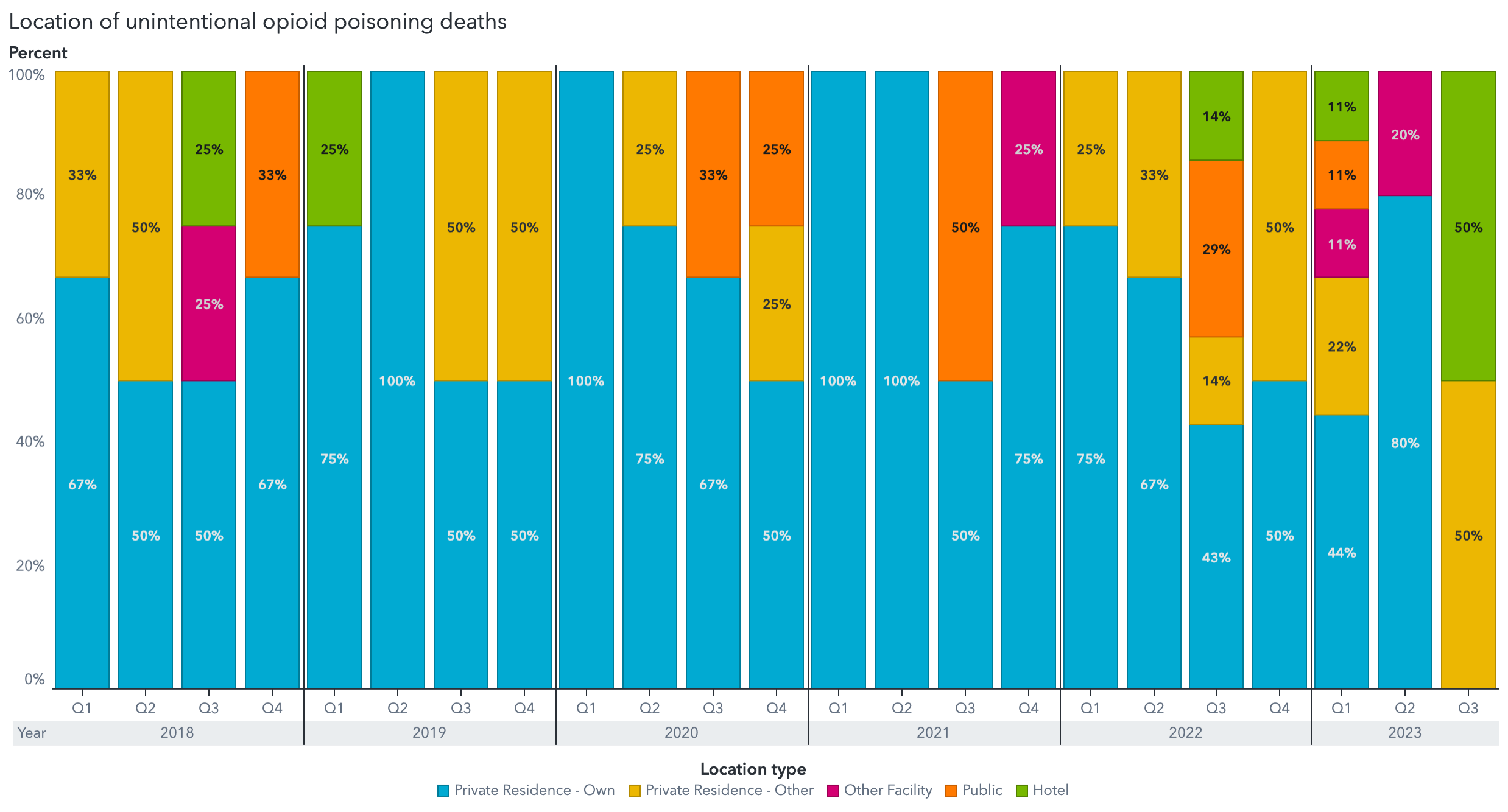

These odds ratios reflect in part the percentage of unregulated drug poisoning deaths occurring in public or in non-housing facilities (primarily shelters for people experiencing houselessness). In tandem with multiple harmful policy manoeuvres, the proportion of drug poisoning deaths occurring in public and in shelters have climbed to staggering levels.

To calculate odds ratios, unhoused and housed population statistics were included alongside these location-of-death percentages.

As the graph shows, the outsized risk of drug poisoning death among unhoused people has grown significantly in most cities in 2023. At the start of the pandemic (Q2-2020), no city in Alberta showed an odds ratio of unhoused/housed drug poisoning death greater than 150-fold—a figure betraying utter abandonment even then.

Now, five of Alberta’s seven largest cities show odds ratios greater than 150, meaning loss of housing puts someone at more than 150-fold higher risk of drug poisoning death.

Together, this represents a collapse in policy responses at every level of government. Local narratives will be highlighted in the sections that follow.

Calgary

Unregulated drug poisoning deaths in Calgary are now dominated by deaths in public (55%) and deaths in shelters (12%). With a counted unhoused population of 2,782 in 2022, 31% of which is Indigenous, systemic racism is rearing its head in the province’s largest city.

In the summer of 2022, an opportunity arose for the city’s largest shelter, the Drop-In, to open an overdose prevention site inside the facility. A local astroturf group formed up to create the impression of public blowback; unfortunately, the East Village Neighbourhood Association also joined in to push back against the planned OPS. Public drug poisonings skyrocketed throughout 2023 in and around the shelter.

In early 2023, the Drop-In netted $4 million in provincial funding to open a detox onsite in place of the planned OPS. Building on a growing body of research, a recent study showed how detox and residential treatment facilities have no impact or negative impact on survival rates for drug poisoning.

Like much of the province, there has been considerable pressure from the provincial government to ramp up policing around areas visited more frequently by unhoused people. These crackdown politics, force-fed to the city through provincial measures such as the public safety task force, are exemplified by increased transit enforcement, encampment evictions, the language of 'open-air drug use,' and large-scale undercover busts. They render unhoused people considerably less safe while making little to no visible impact on crime statistics.

Unhoused people in Calgary are currently 1,032 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people. Calgary maintains a large municipal police force.

Edmonton

Edmonton’s key story recently is around encampment clearing. You can review Edmonton Police Chief Dale McFee’s public record on the topic, which betrays his terrifying zeal in dismantling encampments. This increases risk of drug poisoning death for inhabitants.

But services for unhoused people have been eroding for years. In 2021, the UCP government manoeuvred to close a critical supervised consumption site at Boyle Street Community Services, a facility operating under lease with Oilers Entertainment Group (owned by Katz Group Real Estate) since that same year. In September 2023, Boyle Street was forced out of the location entirely. Development plans for the area have yet to be released.

Unhoused people in Edmonton are currently 454 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people.

Lethbridge

In the summer of 2020, the UCP closed down the only supervised consumption site in the province offering supervised inhalation service. It was also the busiest site in North America. Since then, deaths in public have continuously grown, reaching a peak of 60% of the total deaths in the second quarter of 2023.

Recent discussion in The Conversation highlighted an organized racist hate group that targets unhoused people in the city. Corruption concerns within city's police force became so severe that the UCP had to publicly warn its chief. Unhoused people in Lethbridge are currently 426 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people.

Thank you for reading Drug Data Decoded. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Red Deer

With deaths in public now at 22% and deaths in shelters at 11% of the total, Red Deer city councillors Lee and Higham recently proposed a motion to close down the city’s only overdose prevention site.

According to CBC, the motion calls for the province to increase access to other forms of harm reduction, such as detox beds and medication-assisted treatment, abstinence-oriented services not typically listed under the umbrella of ‘harm reduction.’ It should also be noted that growing evidence shows neither detox nor residential treatment beds are effective at mitigating drug poisoning risk.

This is another politically motivated tragedy waiting to happen, as unhoused people in Red Deer are currently 156 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people. As this disparity is much lower than the cities listed above, it is noteworthy that Red Deer is the first on this list policed by RCMP rather than a municipal force.

Medicine Hat

Shortly after taking power in 2019, the UCP announced the cancellation of a supervised consumption site planned for Medicine Hat. The city has long held a strong commitment to minimizing houselessness.

However, unhoused people in Medicine Hat are now 682 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people, and deaths in public occupy 42% of the total unregulated drug poisoning deaths. Medicine Hat maintains a municipal police force.

Grande Prairie

Grande Prairie keeps a relatively low profile but its unhoused community carries a heavy load: in the third quarter of 2023, half of drug poisoning deaths occurred in public spaces. The city of around 75,000 maintains a supervised consumption site in a mobile van.

Unhoused people in Grande Prairie are currently 206 times more likely to die of drug poisoning than housed people, and the city is currently policed by RCMP as it undergoes a transition to a municipal police force.

Fort McMurray

Fort McMurray has traditionally showed much lower opioid-related drug poisonings than any other Alberta city. It also has a lower frequency of houselessness than any other city in this list with the exception of Medicine Hat.

No drug poisoning deaths occurred in public in Fort McMurray in the third quarter of 2023. The city is policed by the RCMP.

This Christmas, spare a warm greeting, cigarette or meal for your unhoused neighbours. They are probably mourning multiple close friends and family members.