Why is Vincent Lam distorting drug deaths?

The author and addiction physician continues disguising reactionary talking points as medical fact through Globe and Mail op-eds. In his latest, he misrepresents death rates in Timmins, belittles harm reduction and appears to cozy up to Poilievre's abstinence-focused drug strategy.

In his latest of many Globe and Mail op-eds, author and addiction physician Dr. Vincent Lam opens up with another dramatized and de-humanizing depiction of people who use drugs that is unfit to repeat.

Then, after paying brief lip service to supervised consumption, Lam goes all-in on the Alberta Model: "harm reduction has so dominated the public discourse that one could be excused for thinking that it is the only available response to a crisis solely defined by the toxic drug supply."

One could similarly be excused for thinking Lam is working to narrow the scope of public discourse, given that since 2012, the prevalence of substance use disorders has decreased in Canada.

In the same period, drug toxicity deaths increased twenty-fold in some provinces. A key reason is that drug supply volatility and potency have become many-fold higher. In fact, monthly average fentanyl concentrations measured at drug checking sites were directly proportional to monthly poisoning deaths in a Vancouver study.

An overlooked driver of this trend is opioid de-prescribing having been accelerated immediately before fentanyl overran the illegal market. American CDC data provide a clear narrative with obvious parallels in Canada. The key story to follow here is that the demonization of OxyContin, for better or worse, resulted in a mass switch to unregulated heroin. The Afghan opium supply could not keep pace, and synthetic fentanyl filled the gap.

So it makes sense to define the crisis as one rooted in a toxic unregulated drug supply. We are not in an 'addiction crisis,' we are in a mass poisoning that is not addressable through conventional treatment. These facts haven't changed, despite the repetition propaganda coming from certain quarters.

In his piece, Lam does eventually pivot to the tired call for integration of health services to promote access to treatment (including trauma therapy, which we can expect to grow in demand as the poisoned dead leave broken communities behind), housing and wraparound supports for people seeking help with substance use. This is all so glib, it's universally promoted by political parties.

The main trouble is, Lam's prime example to follow is Alberta: holy land for corporate welfare, backroom privatization, deregulation, and a record-breaking year for drug toxicity deaths in 2023 that goes unmentioned in the op-ed.

Meanwhile, Lam's assertions fail to challenge the key structure that underpins the drug poisoning massacre: drug prohibition itself. Paternalistically writing off safe supply and decriminalization as juvenile demands of unenlightened rebels, Lam lays bare his latent conservatism. Sure – we need housing and food security for all, except people who use drugs and refuse to quit.

It's so central to Lam's thinking that he repeats it: "while overdoses need to be reversed, that effort will only have lasting impact if it leads people toward treatment." To shore this up, Lam cites decade-old data showing 38% to 59% reduction in mortality from conventional opioid agonist treatments like methadone or buprenorphine.

But these studies are from another time, before fentanyl replaced heroin. Doctors still clinging to their outdated conclusions are propping up magical thinking that keeps us in a death crisis – one perhaps better characterized as an extension of Indigenous genocide. Contrary to Lam's thinking, drug poisonings are readily preventable through access to a regulated supply, even outside the rigid confines of medical control. Vancouver's Drug User Liberation Front showed this in its peer-reviewed study underpinned by miraculous courage, for which they now face federal trafficking charges. (Speaking of which, please donate to DULF's legal defence and challenge of the Controlled Drugs & Substances Act!)

Rebellious, misguided harm reductionists

Lam asserts that "political finger-pointing and media attention revolve around hot-button issues such as prescribed alternatives (aka safer supply), supervised-consumption sites and decriminalization – all harm-reduction measures. These serve nicely as political wedge issues because they are controversial and challenge societal norms."

By writing it off as simply serving as a political wedge, Lam lays the blame for political division at the feet of harm reduction advocates, while dismissing widespread support for harm reduction measures as rebelliousness for its own sake. He ignores that harm reduction has always been forced by established power structures to prove its methods through robust scientific research – and it has:

- Supervised consumption sites in Lam's own city of Toronto were recently associated with 67% reduction in deaths over a 500m radius.

- Safe supply was associated with a dose-dependent reduction in deaths of up to 91% among people accessing prescribed hydromorphone.

- Decriminalization, if applied correctly, should halt drug confiscations by police. In a Minneapolis geographic study, opioid confiscations by police were associated with a doubling in drug poisoning deaths for a week over a 500m radius.

So, yes Dr. Lam: harm reduction does reduce deaths. We still await the evidence on how the various forms of addiction treatment promoted in your op-ed will address a mass poisoning. When Lam reflects that his "waiting room contains, in addition to patients, its share of ghosts," one has to wonder how many of these deaths were preventable if a wider scope of care – and perhaps, less pressure to move toward abstinence – had been applied.

But the problems in his piece run even deeper.

A page from the Alberta government playbook

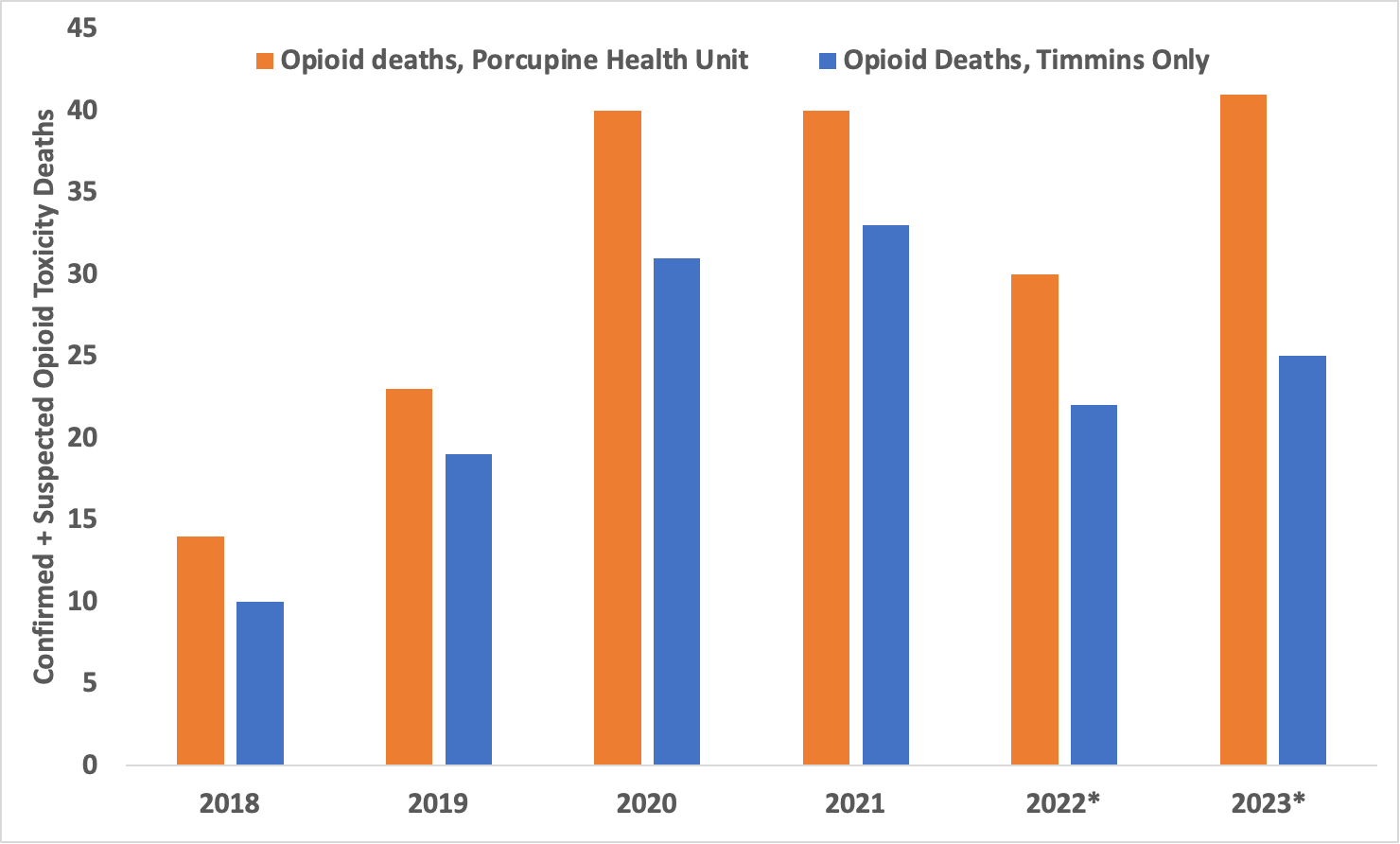

Among his most egregious falsehoods, Lam claims that after Timmins added "14 addiction beds...its overdose death rate has dropped by 50%." This should be corrected by the Globe opinion editor.

First, it appears that Lam is cherry-picking mortality data from 2020 to 2022. Second, he is correct that there was a sizeable mortality decrease in 2022. But it wasn't 50%, it was either 33% (for Timmins) or 25% (for the Porcupine region, in which Timmins is the main centre), in line with many regions in Ontario and across Canada. Further, 2022 data are still preliminary, meaning this apparent decrease from 2021 to 2022 is likely to shrink more. (In Alberta, preliminary mortality counts tend to increase by 10-30% following updates, as understaffed medical examiners manage backlogs).

I reached out to the Ontario Chief Coroner to obtain the latest data (available here), which were at Lam's fingertips at the time his op-ed was published. The data reveal record opioid toxicity deaths for the Porcupine Health Unit in 2023, while the City of Timmins experienced a 14% y/y increase in 2023 that remains below the peak of 33 deaths in 2021. A 50% drop in deaths is nowhere in sight – and it's not close.

For reasons that are unclear, opioid deaths doubled in smaller nearby communities in 2023. It is plausible that increased focus on encampment evictions and pressure by city council to move the city's main shelter out of downtown pushed some people back to their home communities. For its part, Timmins city council seems content to allow its encampment eviction policy to languish in administrative challenges, with one councillor declaring: "If someone thinks that we’re violating human rights, it doesn’t cost nothing to file a case against us." Asking whether local policies are driving an increase in deaths is the type of question that gets erased when a false impression of an easing crisis is amplified by a national newspaper.

Meanwhile, attributing any mortality decrease to the expansion of 'addiction beds' alone is another mischaracterization by Lam. Timmons and District Hospital specifically credited the opening of the city's supervised consumption site to the decrease in deaths, emphasizing that its staff reversed 130 overdoses in its first year of operation and referred around 10% of site visitors to addiction treatment.

It is grimly ironic to publish Lam's op-ed four days after the Timmins supervised consumption site closed for lack of provincial funding, without so much as a mention of the site's planned closure. That has been public since February.

Omitting readily available data to shore up a preferred narrative is propaganda. The Alberta government used it in October 2022 to eliminate safe supply prescribing. Back then, June and July 2022 mortality data were rushed out in September, artificially showing 98 and 99 deaths – low counts, by current abysmal standards. But since then, updates have revealed nearly 30% higher mortalities for both months.

The Alberta government continued to manipulate the public with these false data through 2023, with the premier's chief of staff Marshall Smith stretching them to an outrageous extent in his two-part interview with Jen Gerson. In a response to Gerson, he states that for "October 2022 … [BC] had 179 [opioid] deaths compared to [Alberta's] 92." This claim, unchallenged by Gerson, was false even then: the initial release from the government – I've tracked each one since September 2021 – showed 121 opioid deaths and 127 total drug poisoning deaths. Those data were released on January 21, 2023, eight days after the Gerson interview was published.

Wherever Smith pulled his numbers from, the current figures are 128 opioid deaths and 147 total drug poisoning deaths for October 2022.

As chief of staff to the premier and architect of this War on Drugs rebrand with his political future riding on its perceived success, Marshall Smith might be expected to stretch reality to advance his politics. But Lam's omission of key data from his central example betrays a similarly incurable disinterest in truth.

It is impossible to know what motivates Lam to write these politically congenial op-eds, but their contents make it difficult to ignore the revenue he draws from treating substance use disorders. As discussed in Meet the physicians stonewalling safe supply, Lam billed among the top 5% of Ontario general practitioners in 2017-18, nearly $500,000. This would presumably have occurred through his addiction medicine practice, and it is hard to say if or how much this has changed, as no follow-up has been conducted since the Toronto Star's 2019 report.

Doctors specialized in opioid agonist treatments seem to view safe supply provision as a threat to their business interests. One clinic in London, Ontario spelled it out for us this year:

To be clear: this is not to say that Lam is conducting advocacy to drive greater personal revenue, but the public should not take his medical opinion at face value without understanding that his profession turns private revenues based on client volume. Lam is correct to point out that improved access to methadone, buprenorphine and outpatient treatment – the services he offers – is badly needed. He is incorrect to use the Alberta government as the example to follow, because no measure it has implemented, including virtual prescribing, is being adequately evaluated. The only study on Alberta's Virtual Opioid Dispensing Program (VODP), authored by the system's initiator and longtime lead Dr. Nathaniel Day, made big claims about its success but only proved its abysmal retention rate.

Meanwhile, Lam's advocacy on extending substance use disorder supports into prisons also feels deeply misguided. If "people with addictions are overrepresented in correctional institutions," the first question to ask should be whether caging humans for drug possession, trafficking, and subsistence crimes related to accessing a price-inflated illegal market is justifiable to begin with.

And once again, Alberta is a shining example of how to do this in the most harmful way: the only known contract for linking substance use disorder treatment in provincial prisons appears to have gone to a private company with close ties to the Alberta government. 'Therapeutic Living Units' appear to be the back door for private addiction treatment companies to profit from the prison system.

In early 2022, three clinicians responded to a previous Vincent Lam op-ed, asserting that "the primary outcome of ensuring access to drugs that are not poisoned is survival, not recovery." Lam's wooden-horse promotion of abstinence-as-treatment veiled as an inclusive scope of practice is essentially indistinguishable from current modes of 'care' in Alberta. While it's valuable to support people's recovery journeys how they define them, the main emphasis needs to be placed back on reducing deaths – a discussion the Alberta government and its private treatment allies are doing their best to avoid.

Instead of seeking political alignment with the most regressive governments, Dr. Lam should attempt to explain why harm reduction programs must continually endure public strip-searches while wishful governments pour public dollars into residential treatment, virtual care, 'recovery capital,' Therapeutic Living Units and apps that remain unproven, quasi-religious Hail Maries.

Drug Data Decoded provides analysis on topics concerning the war on drugs using news sources, publicly available data sets and freedom of information submissions, from which the author draws reasonable opinions. The author is not a journalist.